Populism for a Price

August 3, 2007. Story from Washington

Post

ORURO, Bolivia --A llama-wool hat swathing his head, Santos Paredes took the floor with photos in hand -- images of a half-built medical clinic in his village on the high plains of the Andes. Paredes, the mayor, entreated Bolivia's president, Evo Morales, for money to finish the job.

"I

ask for your blessing," Paredes said, laying the pictures across

a red-velvet tablecloth as the president leaned in for a look. Morales was

here to distribute aid supplied by his ideological kinsman, Venezuelan President

Hugo Chávez.

"I

ask for your blessing," Paredes said, laying the pictures across

a red-velvet tablecloth as the president leaned in for a look. Morales was

here to distribute aid supplied by his ideological kinsman, Venezuelan President

Hugo Chávez.

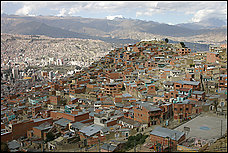

[Click photo to see larger. Caption: New policies promoted by Bolivian President Evo Morales emphasize clinics and education. About two-thirds of the nation's 9 million people are poor. Photo By Peter S. Goodman -- The Washington Post]

"I don't know if I'll give you the money," Morales teased before flashing a grin. Paredes took home a handwritten check for $27,437.

After two decades of reliance on the economic prescriptions of the United States, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, Bolivia has turned left, embracing Venezuelan and Cuban aid, nationalizing industries and championing what its leaders call a pragmatic version of socialism.

Bolivia's break from Washington is part of a regional trend underwritten by Chávez, who has lavished aid on allies to roll back the influence of the United States and Washington-based institutions that have long shaped Latin America's development.

In the past two years, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Argentina and Ecuador have used Venezuelan aid to pay off their debts to the IMF or allow credit agreements to lapse, while adopting unorthodox development strategies that would have been barred so long as they depended on the fund for credit.

Lending by the IMF to Latin America and the Caribbean plunged from $49 billion in 2003 to $759 million last year, according to the fund.

The new course, with its emphasis on health clinics and classrooms for poor communities, draws cheers in many parts of this country of 9 million, where about two-thirds of the population is poor. But economists and political opponents say they doubt it will lift large numbers from poverty.

"These populist policies -- we've already lived through them in Latin America," said Carlos Bohrt, vice president of Bolivia's Senate and a member of the opposition. "They don't create long-term sustainable growth. It's just handouts. This funding could just disappear without any impact."

Since taking office last year, Morales, a former coca grower and the first indigenous tribesman to lead Bolivia, has nationalized Bolivia's oil and gas industry, reversing a privatization orchestrated by the IMF. He forced foreign energy firms to accept drastically diminished profits, increasing the government's royalties by more than $1 billion a year and earmarking the money for schools and hospitals. To gain a free hand, he has ended a credit agreement with the IMF and pulled out of a World Bank body that referees disputes with foreign firms.

"What drives things now is social conscience," said Florencio Choque, a government engineer. "This is rule by the poor."

Detractors say Morales is handing the poor instant gratification at the expense of long-term prospects. Energy nationalization discourages foreign firms from sinking capital into Bolivia, jeopardizing efforts to attract investment to expand production, economists say.

In interviews, Bolivian ministers acknowledged that money from energy royalties extracted from the foreign energy companies outstrips the country's capacity to spend it. About $500 million sits at the central bank, reserved for local governments that have yet to formulate projects.

"There's not yet really a system to absorb this money," Planning Minister Gabriel Loza said.

By accepting cash from Chávez to distribute at will, Morales has undermined Bolivian democracy, opponents say. He has tied his country's fortunes to an impetuous Venezuelan leader who has promised more than he can deliver, they say.

In El Alto, a grim assemblage of low brick houses sprawled across parched plains above the capital, La Paz, the government is sprinkling businesses with grants through a Chávez-funded program.

Elias Condori runs a boot factory in an airless shed in his back yard. For years, Condori applied in vain for bank loans. He says he is grateful for the four new sewing machines he received from the government, along with $3,000 to hire three workers. But without sophisticated stitching machines costing $50,000, Condori cannot compete with factories in Chile. "This doesn't really address my needs," he said.

Economists say such programs could choke the development of competitive businesses.

"As long as they depend on handouts, these small industries are never going to get to a level where they actually create jobs," said Napoleon Pacheco, director of the Milenio Foundation, an economic research institute in La Paz.

Given how little Bolivia's poor have benefited from past policies, the new course is widely embraced here and elsewhere in the region.

Under the direction of the International Monetary Fund, Latin American governments have in recent decades been pressured to welcome foreign investment, privatize industry, limit spending and attack inflation -- a recipe known as the Washington Consensus. That course is widely credited for taming hyperinflation, and it helped spur dramatic economic progress in Chile. But it failed to spark economic growth in some countries, while fostering widening gaps between rich and poor.

Venezuela and the four countries most closely aligned with Chavez -- Bolivia, Ecuador, Argentina and Nicaragua -- collectively saw economic output per person shrink by 10 percent between 1980 and 2003, adjusted for inflation, according to data from the Penn World Table at the University of Pennsylvania. Those countries reported 40 percent economic growth in the two previous decades.

The growth failure helps explain why voters have embraced leftist prescriptions, elevating leaders who have turned away from Washington.

"It's a structural crisis within capitalism, and not just in Bolivia," said Carlos Arze, an economist at the Center of Labor Development and Agrarian Studies, a research institution in La Paz. "United States hegemony over these economies is no longer working."

Previously, the IMF could force governments to adhere to its doctrines or risk losing access to credit. But Chávez, tapping Venezuela's oil wealth, has offered alternative financing, and he's not alone. China is distributing low-interest loans across Africa and Latin America. Private money is surging into developing countries.

"You have an extraordinary amount of liquidity in the world," said Albert Fishlow, an economist at Columbia University. "You have a much greater degree of freedom of individual countries to follow policies that would have previously been punished."

Officials at the IMF cast their diminished role in Latin America as good news, a sign that governments are healthy enough that they no longer require aid. Most countries in the region, Bolivia included, continue to subscribe to the fund's principles, they said.

"We find a much stronger commitment to balanced budgets and low inflation," said Anoop Singh, director of the IMF's western hemisphere department. "This is really a historic breakthrough."

But the nationalization of energy here and in Venezuela broke sharply with IMF counsel, redressing resentment toward foreign treasure-seekers dating to Spanish colonialism, when Bolivia's silver mines enriched a European empire.

Morales and his ministers exude pride in having shaken free of the dictates of Washington. Pablo Solon, Morales's special ambassador for trade, recalled how in 2003 IMF officials concerned about the size of Bolivia's budget deficit pressured the government to increase taxes, sparking riots that killed dozens of people.

"Those were the policies of the IMF," Solon said. "We're applying another recipe."

Bolivia's effort to improve its schools, long overseen by the World Bank, is one example of the policy shift. The World Bank's sector leader for Bolivia, Daniel Cotlear, said the country's average years of schooling nearly doubled between 1992 and 2001. But social advocates say the World Bank did not sufficiently consult with Bolivians on what was needed here.

"The World Bank came with a model and applied it indiscriminately," said Minister of Education Magdalena Cajias. "They ignored Bolivia's sense of its own identity."

Bolivia is now expanding a Cuban literacy program while promoting the use of indigenous languages in addition to Spanish. Last year, the government used energy royalties to distribute $31 million to parents as a reward for keeping children in school -- about $25 per child.

"It's had an impact," said Gumercindo Quenta, a teacher in the town of Huatajata on the shores of Lake Titicaca, an expanse of blue hemmed in by snow-capped peaks. Most children in his classroom trudge two miles from surrounding villages. Their families live in mud-brick homes, coaxing sweet potatoes from the land, subsisting on as little as $50 a month.

"Parents are tempted to keep kids home to help," Quenta said.

The recent Latin American rejection of Washington oversight hasn't affected the World Bank as much as it has the IMF. Where the IMF lends to countries in distress and imposes broad requirements related to economic management, the World Bank tends to lend money for individual projects like building highways and dams and financing education and health care. World Bank officials say they have maintained their role in part by changing with the times, letting countries determine their own priorities.

"The idea that the bank was a monopolistic, omniscient, autocratic institution comes from history," said Marcelo Giugale, a former director for Andean countries. "That bank doesn't exist anymore." He praised Bolivia for "putting forward its own policies."

As Venezuelan cash pours into Bolivia, Morales hands out much of it himself. Eschewing business attire for jeans and the colorfully woven ponchos of his Aymara tribe, he flies to remote outposts -- sometimes on a Venezuelan helicopter -- to satisfy requests.

The three-hour drive from La Paz to Oruro, a mining area where the president recently handed out checks, provided a montage of the poverty that grips Bolivia.

At a quarry carved into reddish-brown flats, men hoisted boulders by hand. A woman lugged a fuel canister down a lonely stretch of road.

Jacinto Calle raises cattle outside Caracollo, a smudge of a town where dogs root through trash. In his 63 years, Calle had never seen a doctor. But when an infection spread across his leg recently, he rode his bicycle three miles to a hospital built last year with gas royalties. The doctors were Cuban, a gift from President Fidel Castro. His leg is healing.

In Oruro, three dozen mayors from surrounding towns jockeyed to get into city hall to ask Morales for a piece of his aid program -- Evo Delivers. The president sat at a table taking notes by hand, a Venezuelan embassy official at his side.

A man in a leather jacket asked for a $65,000 clean water project but offered no files.

"If you have a copy of the contract, give it to me," Morales said. "Otherwise go and sit down."

A woman in a poncho requested $52,000 for a swimming pool. She had no cost breakdown. Morales sent her away.

"I can't believe that so many heads of government can be so irresponsible," he said, fretting openly about corruption. "People are showing up with these big entourages. If you have more than one head of government -- your brother, your cousin -- get rid of one!"

A nervous quiet settled over the room. Morales sighed like a disappointed parent.

"Before, you couldn't find any money," he said. "Now, there's money, but you don't come prepared."