A Radical Gives Bolivia Some Stability

September 18, 2007 - NY Times

By SIMON ROMERO

COCHABAMBA, Bolivia, Sept. 14 — Evening newscasts speak of a country on the verge of balkanization. La Paz and Sucre dispute which city should be the capital. Santa Cruz, in the east, clamors for autonomy. The governor of the province encompassing this bustling city in the Andes has called on President Evo Morales to resign.

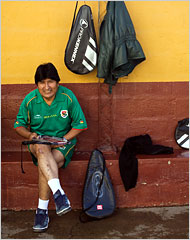

(below, left) President Evo Morales plays frontón, similar to racquetball and loved by Bolivians.

(below, right) Supporters of Evo Morales awaited his arrival at a rally in Cochabamba, Bolivia, the town where he first appeared on the public political scene.

[photos by David Rochkind for The New York Times]

“Step into my office,” said Mr. Morales, at the start of an interview at 5:45 a.m. on a Friday. He opened the door to a barren room in a decaying building here that houses the Federación del Trópico, which represents coca-leaf growers from the jungles of central Bolivia. When in Cochabamba, where he also keeps a modest home, he conducts presidential affairs from this office.

But Mr. Morales, the first Indian to govern Bolivia since the Spanish conquest almost five centuries ago, knows a thing or two about unrest, having organized protests for years as the leader of the country’s cocaleros, or coca cultivators, who fiercely resist American efforts to eradicate their crops.

Mr. Morales’s work habits, inspired by the coca farmer’s custom of rising before dawn, have not changed since he became president in 2006. The sport-utility vehicles of the president’s motorcade sit on the curb. A BMW, one of three he uses around Bolivia, is parked nearby. So is his private jet.

For all the worries that Mr. Morales’s radicalism would create economic and political turmoil in Bolivia, the reality of his tenure is that the country is relatively stable. Social divisions and poverty remain entrenched, but Mr. Morales has surprised many, including some in the business community, with his staying power.

When asked about Bolivia’s problems, he replies with an economist’s precision. “One of the most ferocious debates in my cabinet is whether we should spend part of our foreign currency reserves,” he said, explaining how these reserves had more than doubled since he took office in January 2006, to about $4 billion. In a nod to economic orthodoxy, Mr. Morales said, “I don’t want to for now.”

Bolivia remains South America’s poorest country, with about 60 percent of the population of 9.1 million mired in poverty, making such debates crucial. Yet the results of one of Mr. Morales’s policies in particular -- the nationalization of the petroleum industry last year -- has surprised even skeptics.

Feared as a radical move, the nationalization was in effect a renegotiation of terms with foreign energy companies that have stayed in Bolivia, attracted by the country’s bountiful natural gas reserves. Revenue from oil and natural gas climbed to 13.3 percent of gross domestic product in 2006 from 5 percent in 2004, according to the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington.

That increase has placed Bolivia on its most enviable economic footing in years, with growth of about 4 percent expected this year. Economists also note that coca is lifting Bolivia’s economy, with traffic climbing to neighboring Brazil.

In a touch of irony, the urban upper classes, many of whose members remain explicitly critical of Mr. Morales, are benefiting from the newfound stability and economic vibrancy. With a cocalero in power, cocalero activists no longer shut down the main highway from Santa Cruz, enabling the province’s exports to reach important markets. Similarly, parts of the southern area of La Paz are prospering as builders rush to meet demand for comfortable apartment buildings. Here in Cochabamba, a new $6 million Cineplex, which seems plucked from suburban California, illustrates how investors are pouring money into new projects.

One feature film set to debut on screens throughout the country next month is “Evo Pueblo,” in which the director Tonchi Antezana depicts Mr. Morales’s origins in the Aymara Indian village of Orinoca. The fictionalized account shows his stints in brick factories and how he played trumpet in local bands and his radicalism as head of the cocaleros.

The film reflects a fascination in Bolivia with Mr. Morales, who never graduated from high school and remains a bachelor at age 47. At rallies, crowds hold placards celebrating reports that Mr. Morales is mentioned as a possible recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. Two journalists, Darwin Pinto and Roberto Navia, have caused a sensation with an unauthorized biography called “Someone Called Evo,” which recounts the president’s amorous adventures and his rise to power.

On the political front, critics say Mr. Morales is tilting toward authoritarianism, with rough verbal treatment of opponents and a proposal by supporters to be re-elected indefinitely. And some policies seem erratic and inspired by President Hugo Chávez of Venezuela, like his moves this month to establish diplomatic ties with Iran while announcing visa requirements for American visitors.

“Chávez sees the creation of a great Latin American fatherland, a vision that I share,” said Mr. Morales, defending his aid from Venezuela, while criticizing foreign assistance that requires conditions like coca eradication. He remains the leader of the Federación del Trópico, saying he would return to growing coca when his presidency ends.

For now, Mr. Morales, dressed in jeans and tennis shoes, seems at ease after attaining the highest approval ratings of any president in recent memory. He shoos away advisers and bodyguards, preferring to conduct the interview alone. He jokes about efforts to improve his swing in frontón, a sport similar to racquetball that is beloved by Bolivians.

“We’re creating another way of doing government, but it has not been easy,” Mr. Morales said in halting and carefully enunciated Spanish as the sun rose above Cochabamba. “The challenges seem to arise every day.”

He chafes at criticism from Bolivia’s light-skinned elite. Even as president, he said, he still suffered from discrimination, pointing to snubs and insults from the business community in Santa Cruz, a bastion of opposition to his government.

“I thought that by getting to the presidential palace I could end discrimination,” he said, remembering how his mother was prevented from entering the plaza of Oruro when Mr. Morales was a teenager growing up in that city. “I realize now that the decolonization of our society will take longer than expected.”