(above) Tourists pose on the otherworldly salt flats of the Salar de Uyuni. Over the last 10 years, Bolivia has begun using some of its extremes, like the vast otherworldly salt flats of the Salar de Uyuni, to its advantage. It's become a booming hub of adventure and eco-tourism by appealing to the young and daring who are willing to exchange safety, comfort and convenience for thrills on the cheap. (Photo: Susana Raab for The New York Times)

Adventures in Bolivia

August 10, 2008 - The New York Times

By ETHAN TODRAS-WHITEHILL

THE highway drops precipitously down the mountainside, and the pavement is slick with rain and hail. Cars pass in both directions, forcing me to pedal tight to the thousand-foot drop at the road’s edge. Fog obscures the tops of the striated olive-green and black cliffs on the other side of the valley. Below, it is raining, but at 15,000 feet our little group of adventure seekers is actually inside the cloud, freezing precipitation pelting our hands and faces as we bike downhill at patently unsafe speeds.

SLIDE SHOW: Bolivia's Extremes (12 photos)

(right) Map

(right) Map

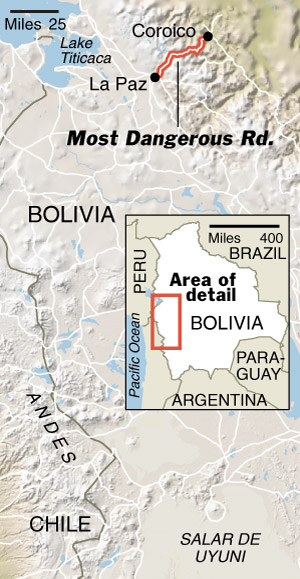

This is the first leg of a cycling day trip on Bolivia’s much-advertised Most Dangerous Road (a k a Death Road), which descends 12,000 feet over 40 miles from a mountain pass near La Paz to the balmy resort town of Coroico. It is third-world infrastructure turned into a tourist attraction.

The grim nickname comes from a report in the 1980s, when Bolivia tried to secure funding to build a replacement road for this one by touting traffic fatalities higher than anywhere else in the world — more than 300 dead in a single year. Since the new road was built, those numbers have dipped drastically but have been joined by a new statistic: cycling deaths, more than one a year.

The guides finally call us to a halt at the first shoulder to wait for the van that took us to the top and will follow us down the road in case of injuries, breakdowns or people’s coming to their senses. I try to unclench my hands from the handlebars but find them locked in position from the cold, my thin racing gloves useless. Water has begun to form icy pools in my shoes.

I ask how soon we’ll be low enough in altitude for the air to feel warm and am informed “another hour or so.” The guides go on to explain that soon after that, we will leave the pavement of the new road and turn onto the old one, a 10-foot-wide, cliff-hugging gravel track. That is the “true” Most Dangerous Road. This is just the warm-up. I look down the foggy road, uncertain if I should continue, and then back up the way we came. The van will be along shortly.

From the snowy slopes of its 20,000-foot peaks to its status as the poorest country in South America, Bolivia is a land of extremes. Over the last 10 years, this country, which for tourists was once a bothersome overland passage between Peru and Argentina, has begun to turn some of its extremes to its advantage, becoming a booming hub of adventure and eco-tourism. It has done so by appealing to the young and daring who are willing to exchange safety, comfort and convenience for thrills on the cheap.

The adventure begins as soon as you get off the plane in La Paz and try to breathe. At 13,000 feet, El Alto International Airport is among the world’s highest, and upscale La Paz hotels keep oxygen tanks on hand for their guests. Clay brick dwellings cling to the walls of the wide canyon that defines the city’s geography; the central artery runs along its floor.

Fifteen years ago, Sagarnaga Street, a steep lane ending at the city’s heart, was lined with stalls selling wool, buttons and thread. Today, a cascade of brash computer-designed signs advertises tourist agencies with names like X-Treme and Downhill Madness. Small groups of young travelers pop in and out searching for the best prices on a trip to the Amazon or a mountain climbing expedition.

The La Paz company that pioneered the Most Dangerous Road cycling tours, for example, Gravity Assisted Mountain Biking, has led more than 33,000 cyclists down the road in the last 10 years, and its business has been growing at a rate of 20 percent annually, even though about 30 other agencies now offer similar services.

Given the significant role tourism plays in the economy of many countries, one might expect growth like this to be a result of a concerted government effort. In fact, the phenomenon of rapidly increasing Bolivian adventure and ecological tourism has been driven completely by private enterprise, according to Luis Hurtado, head of tourism promotion at the Bolivian Vice-Ministry of Tourism. If anything, Mr. Hurtado says, the adventure focus overshadows the government’s own initiatives, like its promotion of indigenous culture tourism on Lake Titicaca.

Three elements have contributed to the phenomenon, all since the 1990s, according to tourism operators I interviewed: increased growth of eco-tourism in Bolivia’s Amazon Basin country to the north, which offers jungle experiences similar to Peru’s but at a deep discount; the development of tourism in the beautiful but extreme salt flats to the southwest; and the popularization of the Most Dangerous Road bicycle journey, which began in 1998.

Traveling in Bolivia is notoriously fraught with difficulty, and not just because of the altitude, which can cause headaches, dizziness and in rare cases life-threatening illness. Local communities often express their frustration with the government by throwing up roadblocks that can leave travelers stranded for days or even weeks. And deficient standards of hygiene mean that gastrointestinal problems are de rigueur for any Bolivian visit.

But to the young and thrill-seeking, for whom “extreme” is a selling point rather than a warning, these traveling tribulations are simply a different sort of adventure.

“You don’t know what to expect from day to day — if you’re going to get food poisoning or if a bus or flight won’t show up,” said Fergal Lyons, 26, an Irish high school teacher who was in my cycling group on the Most Dangerous Road. “It’s great if you’ve got patience.”

I had been to Bolivia’s Amazon region in the summer of 2006. I swam in piranha-infested water, petted a wild anaconda and helped my girlfriend survive an attack of fire ants, but mostly I just swatted mosquitoes and tried to survive the oppressive heat.

On my most recent visit to Bolivia, earlier this year, I headed south to the salt flats of Uyuni. There, it is not the sports or activities that are extreme so much as the simple act of viewing the landscape. On a typical three-day tour of the Uyuni region, six travelers squeeze into the back of a jeep to cover over 600 miles on roads that barely deserve the name. The jeeps travel into altitudes reaching 16,000 feet, and one night is spent at 14,500 feet, the height of the tallest mountain in the continental United States. The vehicles frequently break down. The overnight shelters (“hostels” would be overstating it) are made of blocks of salt and/or mud and have no heating. During the June to August tourist high season in Bolivia, regional temperatures range from about 60 degrees Fahrenheit during the day to below zero at night.

The views are worth it. I flew in on one of the thrice-weekly flights and was quickly packed into a jeep with five other people who were, thankfully, smaller than I am. I spent the next several hours trying to comprehend the Salar de Uyuni. Its vastness and whiteness — at 4,000 square miles, it’s visible from space — resisted all attempts my mind made to put Uyuni in a category it understands. First I thought: ice. Flat, refractive, extreme altitude; it’s got to be ice. But ice isn’t covered with a lattice of polygons formed by the evaporation of the rains, looking like a giant, irregular honeycomb. Then we drove into an area where a thin layer of water covered the flats and mirrored the clouds and mountains. I stepped out into the hot sun and figured: beach. But the crystals below the water were spiky and hard, and the water did not mix with the salt but sat atop like a layer of oil.

We stopped for a few hours at Fish Island, an angelfish-shaped hill covered in megalithic cactuses. From its crest, the tidal patterns of these flats, once a mighty salt lake, were clearly discernible, as if one day a wave of water had swept against the beach and then evaporated before it could wash out again, leaving only a layer of thick white salt as evidence that it ever was.

After lunch, the various groups of travelers spread out in pockets to take pictures of themselves in the setting — a typical tourist activity, but with a twist. Our eyes don’t know what to make of the Salar de Uyuni, and neither do our cameras. Photos set against Uyuni’s glaring white backdrop lack all perspective, which makes taking gag photos one of the flats’ most popular activities. An Israeli woman took a snap of her friend getting crushed between the jaws of a tiger figurine she had brought for the purpose; a young Englishman shot an Australian girl meditating atop the pages of a Lonely Planet guidebook; the Irish couple in my group photographed each other bursting out of an orange soda bottle. It was like live-action Photoshop.

One of the six tourists in our jeep was Alejandro Álvarez, a Bolivian who works as a guide in the Amazon. He had come to Uyuni because his clients were always talking about either their experiences in the salt flats or their plans to visit it. As everyone else slowly passed out after Fish Island, tired from the sun and altitude, Mr. Álvarez remained transfixed on the flats, now covered with the springtime rainwater and reflecting the sky in flawless detail. “It’s like a different planet,” he said.

In retrospect, the first day was a vacation. We spent that night in a hotel made of salt blocks with red satin bedspreads, which felt like an Elvis-era bordello inside a sand castle. Over the next two days and over 20 hours of dusty driving, we would see red- and green-colored lakes, pink flamingos, hot springs, geysers — and endure three flat tires and an empty tank of gas. Our guide was so surly and unhelpful that Mr. Álvarez would not let us use the word “guide” to describe both of their vocations. On the drive back to Uyuni on the third day, he kept sneaking drinks of what may or may not have been beer as he drove.

But again, the adversity was part of the appeal. Our discomfort and annoyance were forgotten amid laughter and fledgling inside jokes as we passed fields of green, red and gold quinoa, herds of grazing vicuña and the occasional lone Andean ostrich sprinting parallel to the road, dust clouds kicking up behind it.

I returned to La Paz via overnight bus, committed to doing the daredevil bicycle trip but dreading it. In my 2006 trip to Bolivia, I had looked into the Most Dangerous Road. I had concluded that on my list of intelligent ways to spend a day, it ranked roughly on par with throwing rocks at a hornet’s nest.

But my sense of adventure tugged at me. And now, in 2008, an important aspect of the trip had changed from when I first learned about it. The replacement highway that the term Most Dangerous Road had been coined to spur into existence had finally been built — it opened in March 2007 — taking cars on a partly different route. On the second part of the bike tour, which still follows the old gravel road and goes along a 10-foot-wide cliffside ledge, cars are now rare, limited to local traffic, giving cyclists more room.

This did not mean, of course, that it was safe. For advice I turned to Alistair Matthew, the founder of the pioneering Gravity Assisted Mountain Biking. The No. 1 cause of serious accidents on the road, he said, is “testosterone exceeding ability.” He urged me to ride cautiously and pick a reputable tour agency, adding, “Remember that you’re not back in the States where the threat of lawsuit might keep a company in line.”

Indeed, some Bolivian travel agencies with offices in other countries do not book the tour for legal reasons. And even the best precautions will not always prevent tragedy. Mr. Matthew’s company lost its first rider in April 2008, a month after my visit: a 56-year-old man who wasn’t even riding recklessly.

AND so I couldn’t have been thinking clearly when, on the Most Dangerous Road in the freezing rain at 15,000 feet, I got back on my bike.

We stopped every 20 minutes or so, just often enough for me to empty the water out of my boots and try to regain feeling in my fingers. As promised, not long after the air warmed, the paved road ended. We took off down a gravelly, rutted pitch more suited to be someone’s driveway than a pan-American highway. The guides would stop and tell us stories about the many hundreds of people who had died at every turn we passed, then remind us to ride along the outside of the road to avoid the nonexistent traffic — two or three feet from sheer cliffs, with guardrails rare — as if we would somehow listen. Frighteningly, the other riders did. (I hugged the mountainside.) When at a snack break one Scottish guy looked over the edge and said, “I’d love to do a base jump off this” (jumping off a cliff armed only with a parachute), I realized what kind of company I was keeping.

Then something funny happened. Whipping around a hairpin curve, we came upon a waterfall in the middle of the road. With no time to calculate how water might affect the already precarious relationship between my wheels and the gravel — much less slow down — I let go of my fear. I ducked under the cool spray, laughing, and pedaled hard to catch up to the rider ahead.

We cruised into the little town that marked the finish, the lush valley’s vegetation pressing onto the road. Behind us, the mountains loomed, still cloaked in sleet and fear but in that glorious moment forgotten. At the end of the Death Road, there was only life: chattering parakeets flying overhead, sweet wildflowers on the wind and we young men and women — sweating, grinning, alive.

JUNGLES, SALT FLATS AND DEADLY ROADS

Bolivia is often visited as a side trip from Peru or as a stop on a larger South American tour. Direct flights to and from La Paz can be time-consuming and expensive. An online search for flights from the New York area for a weeklong trip in mid-September turned up one- and two-stop flights from LAN Peru and its partner American Airlines for $760 and up, flying through Miami and Lima, and two-stop flights from Avianca for $706 and up, flying through Lima and Bogota. An alternative is to fly into Santa Cruz in eastern Bolivia, where quicker one-stop flights from New York, through Miami, were available for $1,000 and up for the same time period. But that puts you farther from the action.

WHERE TO STAY

In La Paz, the best local hotels can be had at a reasonable price — with emphasis on “best” as a relative term. The Hotel Presidente is centrally located with all the amenities Western travelers would expect from a luxury hotel (591-2-240-6666; www.hotelpresidente-bo.com; doubles from $115 in September). Less expensive is the Hotel Eldorado, with serviceable rooms and an excellent staff (Avenida Villazón; 591-2-236-3355; www.hoteleldorado.net). Doubles begin at $40.

WHERE TO BOOK

Tours of the jungle and salt flats can be booked from Rurrenabaque and Uyuni, respectively, but by booking in La Paz you at least have someone to complain to when things go wrong. Joerg Roehner and Susan Rielos de Roehner, owners of Viacha Tours (591-2-231-2967; www.viacha-tours.com), have gone the extra mile for travelers, and Roxana Córdova and her staff at Tawa Tours have been running Bolivian adventure trips longer than anyone else in town (591-2-233-4290; www.tawa-america.com). Tour prices range from $30 to $50 a day or so, not including transportation. Getting to Uyuni or Rurrenabaque is often the biggest adventure of all, via overnight buses or small airplane ($345 round trip from La Paz to Uyuni; your tour agent can help you book).

For the Most Dangerous Road, it is unwise to skimp and go with a cheaper outfitter. The extra costs typically go for items like brake pads and bike maintenance. Alistair Matthew’s Gravity Assisted Mountain Biking (www.gravitybolivia.com) and B-Side Adventures (www.bside-adventures.com) have the best reputations and offer tours for around $70 for the day, but their tours fill up a day or two in advance, so book early.