A Revolutionary Icon, and Now, a Bikini

Published Oct. 9, 2007, NY Times

By MARC LACEY

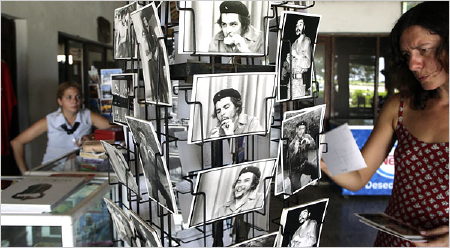

SANTA CLARA, Cuba, Oct. 8 — Aleida Guevara March, the 46-year-old daughter of Che Guevara, says she can bear the Che T-shirts, the Che keychains, the Che postcards and Che paintings sold all over Cuba, not to mention the world.

(photo, right) A tourist looked at Che Guevara post cards for sale in in Sanata Clara, Cuba. Photo by Jose Goitia for The New York Times

(photo, right) A tourist looked at Che Guevara post cards for sale in in Sanata Clara, Cuba. Photo by Jose Goitia for The New York Times

At least some of the purchasers truly cherish Che, she says. On Monday she was surrounded by thousands of Che fans wearing his image here in Santa Clara, where her father’s remains are kept, and where she sat in the front row of a ceremony to observe the 40th anniversary of his death.

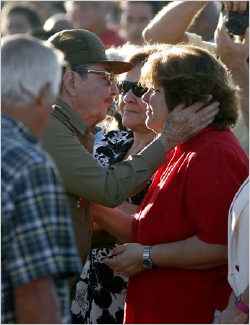

(photo, left) Raúl Castro with Aleida Guevara March, right, daughter of Che Guevara, and Aleida March, center, Che’s widow, at a ceremony Monday for the 40th anniversary of Che’s death. Photo by Jose Goitia for The New York Times

Raúl Castro, the acting president, attended. A message was read from his older brother Fidel, who ceded power in August 2006 after emergency surgery, likening his former comrade-in-arms to “a flower that was plucked from his stem prematurely.”

But amid all the ceremony, what really gets to Ms. Guevara is the use of the man she calls Papi in ways that she says are completely removed from his revolutionary ideals, like when a designer recently put Che on a bikini.

In fact, 40 years after his death, Che — born Ernesto Guevara de la Serna — is as much a marketing tool as an international revolutionary icon. Which raises the question of what exactly does the sheer proliferation of his image — the distant gaze, the scraggly beard and the beret adorned with a star — mean in a decidedly capitalist world?

Even in Cuba, one of the world’s last Communist bastions, Che is used both to make a buck and to make a point. “He sells,” acknowledged a Cuban shop clerk, who had Che after Che staring down from a wall full of T-shirts.

But at least here he is also used to inspire the next generation of Cubans. Schoolchildren invoke his name every morning, declaring with a salute, “We want to be like Che.” His quotations are recited almost as often as those of Fidel Castro.

“There’s no doubt that when Fidel dies someday, his image will be just like Che’s,” said Enrique Oltuski, the vice minister of fishing and a contemporary of both men. But Che’s mythic status as a homegrown revolutionary does not extend everywhere, even if his image does. When Target stores in the United States put his image on a CD carrying case last year, critics who consider him a murderer and symbol of totalitarianism pressed the retailer to pull the item.

“What next? Hitler backpacks? Pol Pot cookware? Pinochet pantyhose?” Investor’s Business Daily said in an editorial, calling the use of the image an example of “tyrant-chic.”

That famous image of Che, by a Cuban photographer, Alberto Korda Díaz, was taken at a March 5, 1960, funeral rally for dozens of Cubans killed in a boat explosion for which Cuba blamed the United States. The picture became famous after appearing in Paris Match magazine in 1967, just weeks before Che was killed by soldiers in Bolivia, apparently aided by the C.I.A.

Mr. Korda, who died in 2001 at age 72, never received royalties but did sue a British advertising agency over the use of the photo for a campaign promoting vodka. He won $50,000, which he donated toward buying medicine for children.

Ms. Guevara and her family, too, have tried to stop the marketing of Che’s image in ways that they find abhorrent. She says they have reached out to lawyers in New York, whom she would not identify, to pursue companies the family thinks are misusing the image, not to sue them for damages, but to ask them to stop.

“We’re not after money,” she said. “We just don’t want him misused. He can be a universal person, but respect the image.”

Some of Che’s star power has rubbed off on his four surviving children, one of whom is named Ernesto Guevara and drove to the memorial on a motorcycle, just like Dad. Cubans hug the Guevaras in the street, and tourists are giddy when they learn who they are.

“I have goose bumps,” said Alfredo Moreno, 32, a Mexican who posed for a picture with Ms. Guevara, clearly overcome with emotion. “I can’t describe to you what this moment means to me.”

As Mr. Moreno went on and on, Ms. Guevara told him to stop his fawning words.

“I’m a child of Che,” she explained, “but I’m not Che.”

Ms. Guevara is in fact a pediatrician and mother of two who favors pantsuits over military fatigues. She resembles a Cuban soccer mom more than a revolutionary.

Her sister is a veterinarian. One brother manages a center devoted to Che in Havana. Then there is Ernesto, a Harley-Davidson aficionado. All are called on by the Cuban government from time to time to help continue their father’s legacy.

It is not hard to detect a bit of exhaustion in all this, particularly now, when Cuba and much of Latin America are holding major events to honor both his death and, next June, what would have been his 80th birthday.

“I can’t be everywhere,” Ms. Guevara said. “I can’t multiply myself.”

Ms. Guevara travels the world speaking at conferences dealing with Che. At one in Italy, she learned after signing T-shirts for some young people that they were fascists. “They knew nothing about him,” she said with a sigh.

Once, she said, she bumped into John F. Kennedy Jr. in Europe and discussed with him the challenges of being the offspring of a famous man.

She called him “a beautiful person,” and said she was able to separate him from his father, who ordered the Bay of Pigs invasion to try to topple the government that Che had helped put in place in Cuba.

But bring up United States foreign policy, and the resemblance to her father really emerges. The fiery speech flows when she discusses the war in Iraq. She calls the economic embargo of Cuba that has stretched on for 50 years “so brutal, so stupid, so irrational.”

And don’t even get her started about the Bush administration.