(above) Supporters of the president marched this month toward Santa Cruz, a stronghold of opposition.

(above) Supporters of the president marched this month toward Santa Cruz, a stronghold of opposition.

(Photo: Dado Galdieri/Associated Press)

Fears of Turmoil Persist as Powerful President Reshapes Bitterly Divided Bolivia

September 27, 2008 - The New York TImes

By SIMON ROMERO

SANTA CRUZ, Bolivia -- At first glance around this rebellious city, President Evo Morales seemed to have suffered a sharp setback this month. Mobs looted nearly every federal building, strewing offices with broken furniture and spraying walls with graffiti calling him a vassal of President Hugo Chávez of Venezuela in explicitly racist language.

Skip to next paragraph

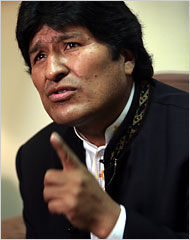

(left) Evo Morales is the most popular Bolivian president in years.

(left) Evo Morales is the most popular Bolivian president in years.

(Photo: Bebeto Matthews/Associated Press)

The devastation is telling of the turbulence of Bolivia's politics these days. But it belies Mr. Morales's gathering strength in the country at large, and the stresses it has placed on Bolivia's wobbly democratic institutions, which he has set about recasting amid rising violence by his supporters and opponents alike.

The election of Mr. Morales, Bolivia's first indigenous president, in 2005 was a watershed in South America, as long-marginalized native peoples took power for the first time -- through the ballot box.

Increasingly, the question confronting Bolivia, a country of deep ethnic and geographical divisions, is how they will wield that power, and whether Mr. Morales can redress the historical grievances of Bolivia's indigenous majority while keeping his country from descending into chaos.

"It's been half a century since Bolivia has had a president with such power and public support," said Gonzalo Chávez, a Harvard-trained political analyst at the Catholic University of La Paz. "Now we have to see how Evo proceeds with plans for a radical reconstruction of the state and with what methods."

Mr. Morales now faces strong -- and frequently violent -- protests in lowland departments that are home to most of the nation's petroleum reserves and a European-descended elite that sees its interests as threatened.

But Mr. Morales appears more and more likely to get the constitutional changes he wants to spread land reform, create a separate legal system for indigenous groups and allow him to run for re-election, proposals that have the potential to keep him in power for the next decade.

As violent as his opponents have sometimes been, they charge that Mr. Morales is achieving much of this by running roughshod over them. They say he has ignored court rulings that challenge his policies and used some of the same intimidation tactics he honed as a leader of the powerful coca growers unions before he was elected president.

As such tactics spread on both sides, fears are growing throughout the region that Bolivia's crisis could produce, if not civil war, then pockets of fierce conflict across its rebellious tropical lowlands, which are an important source of natural gas and food for neighboring countries.

Last week, thousands of Mr. Morales's supporters, some wielding dynamite sticks and shotguns, marched toward Santa Cruz to press leaders here to sign an agreement on a timetable for approving the new constitution. The marchers clashed with regional officials, beating them with sticks when they tried to persuade them to disarm, before relaxing their actions.

In a veiled threat, Mr. Morales said that "peace and tranquillity" would return to economically vibrant Santa Cruz if its leaders agreed in talks under way to create a framework for putting his proposed constitution to a vote.

Mr. Morales is also pressing the lowlands to share more of their oil and gas royalties, money he is already using to alleviate some of the crushing poverty found across Bolivia, one of South America's poorest countries.

But as Mr. Morales asserts control over federal bureaucracies, which he and his supporters say were long engineered to serve the interests of the elite, his opponents fear those same institutions are being stacked against them.

The president's supporters also are winning key victories in Congress. And as opposition has moved to regional governors and outlying departments, Mr. Morales has sought to preserve centralized power in La Paz.

Before traveling to New York last week for the opening of the United Nations General Assembly, Mr. Morales imprisoned a top opponent -- Leopoldo Fernández, governor of Pando, a small Amazonian department where resistance to the central government has been strong -- accusing him of ordering the massacre of more than a dozen rural workers.

At the same time, the president quelled concern about dissent in the armed forces by installing an admiral to run the department in the governor's place during a state of siege.

Still, by adopting some of the same tactics Mr. Morales once used to destabilize previous elected governments in Bolivia, like road blockades and street protests, his opponents have found themselves on the defensive.

Mr. Morales has received the backing of neighboring governments, who fear Bolivia's turmoil will threaten their energy supplies and want to see the conflict resolved. President Michelle Bachelet of Chile led a meeting of Unasur, a nascent political association of 12 South American countries, on Wednesday to discuss the crisis.

Without offering proof, Mr. Morales accused his critics of plotting a "civil coup" with the help of the American ambassador, Philip S. Goldberg, whom he expelled abruptly on Sept. 10.

Indeed, considerable ill will toward the United States persists in Mr. Morales's government, particularly in relation to a United States agency called the Office of Transition Initiatives.

Washington ended the office's operations in Bolivia last year, after dispensing grants aimed at strengthening departmental governments, which have taken the lead in opposing Mr. Morales.

"Our work with local governments -- both pro-government and opposition -- sought to help these governments improve their ability to deliver services to their population," said Jose Cardenas, assistant administration for Latin America at the United States Agency for International Development, which oversees the Office of Transition Initiatives. "Any claims that our programs went beyond these purposes are baseless."

A commanding force in Bolivian politics for decades, Washington still gives Bolivia more than $100 million a year in aid, much of it to fight the cocaine trade. Increasingly, it looks as if that money and other cooperation efforts may not survive the low point of relations between the countries.

In a move that could throw more than 10,000 jobs in Bolivia into doubt, President Bush said Friday that the United States was preparing to suspend preferences that allow Bolivian exports like textiles to enter without duties. citing a failure to cooperate in antidrug efforts.

Still, American officials, bracing for a further deterioration in ties, now seem relatively powerless to influence events here, even as Bolivia tips toward greater instability. As it moves further from Washington's orbit, it shifts into the pull of Mr. Chávez.

"We see two revolutions playing out in Bolivia, one in the highlands that is indigenous-focused with a democratically elected leader, but at the same time with an antiglobal component," a senior State Department official said in an interview, requesting anonymity because of the tense relations with Bolivia.

"The second revolution, in the lowlands, is for decentralized government, but quite frankly has to overcome racism," the official continued. "What's worrying to us is stitching these two processes together when the extremes on both sides are using violence."

Concerns are growing over those caught in the middle of those clashes, particularly journalists covering the episodes and impoverished partisans on each side of the struggle.

Before the latest crisis, Mr. Morales was already benefiting from the opposition's missteps, like its proposal for a referendum on his policies that was held last month. He emerged victorious with more than 67 percent of the vote, a significant increase from the 53.7 percent he garnered in presidential elections in 2005.

While governors in lowland departments emerged from the referendum with similarly strong mandates, voters recalled two of Mr. Morales's opponents, in La Paz and Cochabamba.

Since then the intensity of the protests seems to have surprised even some opposition leaders, who now say they hope both sides can step back from the brink.

"I do not want Evo toppled in a coup," said Branko Marinkovic, a wealthy landowner who is president of the Pro-Santa Cruz Committee, a group seeking greater autonomy for Santa Cruz from the central government. "I want Evo to finish his term while respecting our dignity in a unified Bolivia."