Bolivia's Burning Question: Who May Dispense Justice?

Draft Constitution Would Allow Indigenous Groups To Judge and Punish

Saturday, February 2, 2008; Page A10 - Wasington Post

By Monte Reel, Washington Post Foreign Service

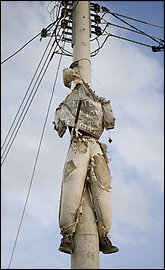

EL ALTO, Bolivia -- Tattered dummies look down on this city from street poles in barren squares, like scarecrows for anyone with bad intentions.

The dummies are meant to warn would-be thieves that if they try to rob anyone here, they could be hanged. Or lashed to a pulp. Or set on fire. Or buried alive.

(left photo) Bolivia's vice minister for communal justice, Valentín Ticona Colque, backs proposals to legitimize penalties doled out by local leaders and communities. (right photo) (Photos By Evan Abramson For The Washington Post) |

|

|

"If there are cases in which people are caught in the act, why can't we take justice into our own hands?" asked El¿as Gomes, a community leader in an El Alto neighborhood where two accused thieves were burned alive by an angry crowd of residents in November. "We want the people of the neighborhood to be the ones to judge the crimes. Beyond the question of whether lynchings are good or bad, we want to be the ones to judge."

Determining who gets to judge criminals is a matter of national debate in Bolivia, where a draft constitution that has already won preliminary approval would make punishments doled out by indigenous leaders and tribal communities as legitimate as sentences handed down by the country's courts.

The proposal has invigorated communities such as this, where many residents maintain strong links to Aymara and Quechua indigenous traditions and few trust what they call the "ordinary justice" system of police, judges and courtrooms. But the prospect of communal justice, as the practice is known, terrifies others, who consider the idea a step toward mob rule.

The definition of communal justice remains open to interpretation, even among populations that have imposed it for centuries without legal recognition. This much everyone agrees on: The decisions are made swiftly, and they mostly involve corporal punishment, such as whipping. Other typical penalties include lynching and shearing the hair of a woman who has been deemed unfaithful to her husband.

Groups of tribal elders usually hand down the rulings. Among Aymara Indians, for example, the decisions are customarily made by "ayllus," the same governing councils that play a role in community decision-making.

Officials here say that Bolivians who identify themselves as indigenous -- a majority of the country's population -- deserve alternatives to government institutions that they believe are discriminatory, corrupt and out of touch with their traditional cultures.

Valent¿n Ticona Colque, a vice minister in charge of communal justice in President Evo Morales's government, said such justice is less likely to be corrupt because it is administered by active members of the communities themselves, not by state-supported judges.

"When the community is involved and vigilant, it's difficult to corrupt the system -- almost impossible, in fact," he said.

According to one article of the draft constitution, decisions made under the communal justice system would be immune from challenge by any outside judicial system. The constitution does not spell out how justice should be dispensed but states that indigenous and campesino, or peasant, authorities "will apply their own principles, cultural values, norms and procedures."

Morales's allies approved the charter in a constitutional assembly late last year, but some opposition groups boycotted the gathering. The draft must now be ratified by a popular vote. It is still unclear when that vote might take place.

What is clear is that the distinctions the document draws between indigenous populations and other Bolivians mirror the political tensions roiling the country under Morales, an Aymara Indian and Bolivia's first indigenous president. Morales's efforts to promote the proposed constitution have been accompanied by deadly street riots and a bitter stalemate between the government and its opponents.

Former president Carlos Mesa, writing last week in La Raz¿n, a La Paz newspaper, said the architects of the proposed constitution have "brought racism into the text."

Backers of the charter said the proposals are meant to apply more to rural areas than to the cities. El¿as Mamani, an Aymara leader from the rural Altiplano region, said communal justice is far more effective and efficient in areas where there are no police and residents cannot afford legal representation.

"Today, when someone breaks a law, they are punished in the ordinary justice system for years -- five, six or maybe 10 years," he said. "But in the community, the punishment sometimes lasts just five minutes and it is solved -- the person does not do it again."

Ricardo T¿llez Rua, the chief of homicide investigations in the El Alto police department, said he is afraid that the Aymara and Quechua communities in this city -- especially around its more undeveloped fringes -- will use government recognition to further embrace do-it-yourself justice.

On the wall of his office hangs a city map cluttered with silver thumbtacks, each marking the site of a recent crowd attack. According to his records, there were 29 such attacks in El Alto last year, 10 of them fatal. A picture displayed in an adjoining office shows the charred bodies of the two accused thieves who were burned to death in November.

What worries him, he said, is that residents don't distinguish between communal justice and mob violence.

"When they capture a delinquent, a lot of times the person might not even be the one who committed the crime," he said. "They might capture a drunk who was confused and just wandered into the wrong neighborhood. The neighbors come out and yell, 'Here's the thief!' and suddenly 50 or 60 people are running at him with sticks and clubs."

Idon Chivi Vargas, a lawyer who helped draft the proposed constitution's communal justice articles as a representative of Morales, said the document itself represents a pledge by the indigenous communities to avoid lynchings. It is a matter of honor, he said.

"The constitution is a promise, and for the first time we are part of the promise," he said. "Now, if anyone is killed, we have gone against our word. We have to do what we have promised -- unlike capitalism, which promises a lot and does nothing."

Political ideology creeps readily into the debate, and opposition figures say they fear that communal justice might be used to terrorize those who do not share the government's socialist beliefs.

Luis Eduardo Siles, a three-term opposition legislator until 2005, said the environment here was particularly bad during Morales's campaign for the presidency.

"In the 2005 campaign, you couldn't go to some places in the Altiplano to campaign if you were not on Morales's side. They'd smile at you and say, 'There's going to be communal justice if you come here,' " he said. "That means if you'd go there to give out T-shirts or something, they'd hang you! So it was too risky to go there."

Siles has compiled a long list of lynchings and related incidents purportedly carried out in the name of communal justice. In one incident last April, an accused thief was about to be lynched when police rescued him. The Bolivian television network Unitel showed Roberto de la Cruz, a councilman in El Alto who was briefly interim mayor, among the crowd preparing to dole out the punishment.

In an interview last week, de la Cruz said he didn't believe lynchings were examples of communal justice, but he did not explicitly condemn them.

He did, however, describe the events of October 2003 -- when riots caused ex-president Gonzalo "Goni" S¿nchez de Lozada to resign -- as an example of communal justice.

S¿nchez de Lozada had dispatched security forces to break through roadblocks in El Alto to clear the way for supply trucks, resulting in dozens of deaths. The incident sparked mass civil unrest throughout the country that led the president to step down.

"That was communal justice, because Goni was expelled from the community -- from all of Bolivia," said de la Cruz, who had helped close the roads in El Alto. "He committed crimes against humanity in Bolivia. . . . Whatever person does something like that, then the same thing could happen to them. They should take note of that."