Related article: Bolivia seeks charges against US rancher April 19, 2009 - AP

American Rancher Resists Land Reform Plans in Bolivia

May 9, 2008 - NY Times

By SIMON ROMERO

(above) Duston Larsen, center, son of Ronald Larsen, on his family's ranch in Bolivia, where the central government wants to break up large holdings and redistribute the land to farmers. (Photo: by Noah Friedman-Rudovsky for The New York Times)

(above) Duston Larsen, center, son of Ronald Larsen, on his family's ranch in Bolivia, where the central government wants to break up large holdings and redistribute the land to farmers. (Photo: by Noah Friedman-Rudovsky for The New York Times)

CARAPARICITO, Bolivia -- From the time Ronald Larsen drove his pickup truck here from his native Montana in 1969 and bought a sprawling cattle ranch for a song, he lived a quiet life in remote southeastern Bolivia, farming corn, herding cattle and amassing vast land holdings.

But now Mr. Larsen, 63, has suddenly been thrust into the public eye in Bolivia, finding himself in the middle of a battle between President Evo Morales, who plans to break up large rural estates, and the wealthy light-skinned elite in eastern Bolivia, which is chafing at Mr. Morales's land reform project to the point of discussing secession.

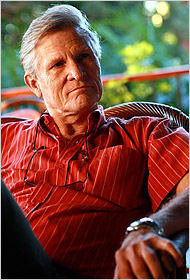

(left) The Larsen family patriarch, Ronald, an American, has clashed with Bolivian officials over the working conditions of the Guaraní Indians he employs. (Photo: Noah Friedman-Rudovsky for The New York Times)

(left) The Larsen family patriarch, Ronald, an American, has clashed with Bolivian officials over the working conditions of the Guaraní Indians he employs. (Photo: Noah Friedman-Rudovsky for The New York Times)

After armed standoffs with land-reform officials at his ranch this year, Mr. Larsen made it clear which side he was on, emerging as a figure celebrated in rebellious Santa Cruz Province and loathed by Mr. Morales 's government, which wants to reduce ties to the United States.

"I just spent 40 years in this country working my land in an honest fashion," said Mr. Larsen, who resembled Clint Eastwood with his weathered features and lanky frame. "They're taking it away over my dead body."

Mr. Larsen's standoffs with the central government, replete with rifles, cowboys and Guaraní Indians, might sound like something out of the Old West. In fact, the battle playing out in the cattle pastures and gas-rich hills of his ranch, amid claims of forced servitude of Guaraní workers in the remote region, exemplifies Bolivia's wild east.

Tensions here erupted one day in February when Alejandro Almaraz, the deputy land minister, arrived before dawn at the entrance to Mr. Larsen's Hacienda Caraparicito to carry out an inspection, a step usually taken before the government seizes ranches and redistributes them among indigenous farmers.

(below) Guaraní Indians employed by Mr. Larsen. (Photo: Noah Friedman-Rudovsky for The New York Times)

Both sides differ as to what happened, but everyone agrees that some violence ensued. "I didn't want this guy making any trouble, so I shut him up with a shot at one of his tires," Mr. Larsen was quoted as saying last month by La Razón, Bolivia's main daily newspaper.

(left) Map. Ronald Larsen bought his land in Caraparicito in 1969.

(left) Map. Ronald Larsen bought his land in Caraparicito in 1969.

Mr. Almaraz said he was kidnapped and held for a day on Mr. Larsen's ranch. He responded to the incident by identifying the American rancher and his son Duston in a criminal complaint for "sedition, robbery and other crimes."

Faced with a legal tussle over the standoff, Mr. Larsen now claims that he did not shoot at Mr. Almaraz's vehicle. "The tires were punched out with sharpened screwdrivers," Mr. Larsen said. "If I'd have been shooting at people that day, there would have been dead and injured."

At stake is the 37,000-acre Caraparicito ranch, which Mr. Larsen bought in 1969 for $55,000, and other holdings of more than 104,000 acres, the government estimates. Mr. Larsen, who as a protective measure transferred ownership of almost all his land to his three sons, who are Bolivian citizens, declined to say how much land his family owned.

With his reserved demeanor, Mr. Larsen, a descendant of Danish immigrants to the Midwest, made it seem as if it were the most natural thing in the world to have moved to Bolivia in the 1960s, after he got bored working as a department store manager.

"A buddy of mine in the Peace Corps told me Bolivia was a good place to invest," he said.

His quiet style contrasts with that of his oldest son, Duston, born in Bolivia, reared in Nebraska and educated at Montana State University. While Mr. Larsen prefers to lie low at the family home in Santa Cruz, the provincial capital, Duston, 29, has been in the spotlight since moving here in 2004.

Within months of his arrival, he won the Mr. Bolivia beauty pageant. He compensated for his American-accented Spanish at the finale by shouting, "Viva Bolivia!" before the stunned judges. Shortly afterward, he was cast as himself in a Bolivian comedy about cocaine smuggling entitled "Who Killed the White Llama?"

Now Duston Larsen is focused on guarding the family's land, ahead of his marriage to Claudia Azaeda, a talk show host and former beauty pageant winner. Depicted in newspaper cartoons as a gun-slinging "Mr. Gringo Bolivia," he basks in the showdown with Mr. Morales, an Aymara Indian who as Bolivia's first indigenous president has made land reform a top priority in his efforts to reverse centuries of subjugation of the indigenous majority.

"Evo Morales is a symbol of ignorance, having never even finished high school," Duston Larsen said.

He vehemently asserted that ranch hands and their families were free to come and go, after the Larsens and other ranchers were faced with government claims that ranches in their region held their Guaraní workers in servitude; the government has used the charge to move ahead with land seizures.

The reality of life at Caraparicito and other ranches may be more complex than either side suggests. At Caraparicito, workers get work contracts, food, clothing, housing and education for their children at a schoolhouse on the ranch. But wages remain low, with senior farmhands earning less than $6 a day.

"We are not slaves," said Oscar Robles, 52, a ranch hand for almost two decades. "But we are not prospering. We just exist."

In 2004, the French energy giant Total discovered one of the largest unexploited natural gas deposits in Bolivia, called Incahuasi, on the ranch. The rights to such discoveries automatically go to the government in Bolivia.

But Mr. Larsen said he believed that one reason the central government was so interested in his land was its natural gas. President Morales could bypass the province of Santa Cruz in reaching deals related to the natural gas field if he is able to settle Indians on the land who are sympathetic to his government.

The combination of oil, guns and land becomes even more combustible when mixed with Bolivia's volatile politics. In a sharp rebuke of Mr. Morales's socialist-inspired policies, Santa Cruz Province approved measures on Sunday that would halt land redistribution and allow provincial officials to renegotiate some energy deals.

Such a vote, which some people in the province consider a possible precursor to secession, might be expected to halt the maneuvers around Caraparicito. Indeed, Mr. Larsen's battle is being watched closely throughout Santa Cruz, where foreign agricultural settlers include Brazilians, Canadian Mennonites, Okinawans and a handful of Americans.

Each side is digging in its heels for the next stage in the fight.

Juan Carlos Rojas, the director of Bolivia's land reform agency, said the battle got personal when Mr. Larsen issued a veiled threat against him and other officials when the American rancher referred to a well-known incident in the 1980s in which he shot dead three intruders inside his home.

"Larsen made it clear that he was above the law," said Mr. Rojas, who emerged from an April standoff at Caraparicito with his face bloodied from a rock-throwing exchange. Echoing comments by Mr. Morales, he said Santa Cruz's newly approved autonomy was "illegal" in his view.

"The last I looked, the Larsens were living in Bolivia and not the Republic of Santa Cruz," Mr. Rojas said. "Despite Ronald Larsen's resistance, we are going to get into his ranch."