Returning the Condor To South

America's Skies

Zoo Group Painstakingly Tends Eggs, Hatchlings

December 29, 2007. pA12 - Washington Post

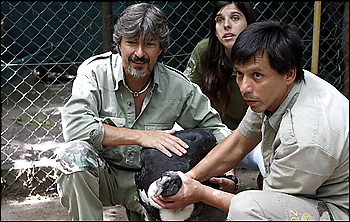

(below-left) Luis Jacome, left, is head of the

Andean Condor Conservation Project. Here, he and volunteers take a blood

sample during a checkup for a condor rescued after it broke its wing.

Volunteers have saved nearly 60 adult condors, nursing them back to health

before releasing them. (Photos By Silvina Frydlewsky

For The Washington Post)

(above-right)

A chick interacts with a hand puppet made to look like an adult bird. Chicks

initially live in special boxes and do not see their caretakers, which

prevents them from associating humans with survival. (Silvina

Frydlewsky - Twp)

(above-right)

A chick interacts with a hand puppet made to look like an adult bird. Chicks

initially live in special boxes and do not see their caretakers, which

prevents them from associating humans with survival. (Silvina

Frydlewsky - Twp)

By Monte Reel, Washington Post Foreign Service

Saturday, December 29, 2007; Page A12

BUENOS AIRES -- The conservationists tend to get a little tense when they approach Egg 54, which sits alone on a metal tray inside an incubator, absorbing warm air like some sort of fragile, slow-baked potato.

The egg might contain an Andean condor, which is why everyone who comes near it wears cotton face masks and avoids sudden movements, standing stiff with caution.

An endangered species, condors cannot reproduce until they are 8 to 12 years old. Even if they manage to survive to that age, they can lay only one egg every three years. Many of those eggs turn out to be infertile.

For the past decade, a team of scientists and volunteers at the Buenos

Aires Zoo has been raising condor hatchlings and releasing them throughout

South America, helping restore populations of the bird in places where

it had long been considered extinct.

For the past decade, a team of scientists and volunteers at the Buenos

Aires Zoo has been raising condor hatchlings and releasing them throughout

South America, helping restore populations of the bird in places where

it had long been considered extinct.

"When you talk to some of the older people in the small, rural communities, they remember seeing condors when they were children," said Luis Jacome, director of the Andean Condor Conservation Project. "Now they're seeing them again."

As its name implies, Egg 54 -- received from a provincial zoo in Argentina -- is one of several dozen that the program has tried to incubate at its headquarters in the Buenos Aires Zoo. Since 1997, 18 of the eggs have hatched condor chicks. Along with nearly 60 adult condors that program members have rescued and nursed back to health, the grown birds now fly in South American skies ranging from Venezuela in the north to Tierra del Fuego at the continent's southern tip.

The Andean condor is one of the largest flying birds in the world. It's a symbol of pride across South America, its image incorporated into the national emblems of Chile, Bolivia, Ecuador and Colombia.

"For us, the condor is a sacred bird," said Tayta Ullpu, a Bolivian of Quechua Indian descent who lives in Buenos Aires and has worked as a volunteer for the project. "It is considered to be the link between us and the heavens, so it's very important that we work to save it."

Condor populations declined for decades throughout South America mainly because of hunting by farmers, many of whom mistakenly believed the condor to be a predatory bird. They would see condors swooping down toward their livestock and then notice that one of their animals was dead, Jacome said. But the birds, which feed solely on carrion, were attracted to the farms because an animal had already died.

Other common threats to condor populations include pesticide poisoning and collisions with high-tension electric wires, Jacome said.

Estimating populations of condors is extremely difficult because their nests are usually in mountainous locations that are difficult to reach, and the birds regularly venture hundreds of miles from those bases.

In 1965, the condor was declared extinct in Venezuela, and it was believed

to be on track for the same fate in Ecuador and Colombia, Jacome said.

On the coast of Argentina -- the country that historically had the largest

condor population-- the bird had also disappeared.

ad_icon

But today, about a dozen condors live in Venezuela, and a total of perhaps 100 soar in the skies of Colombia and Ecuador. Quite a few nest near Argentina's coast, where the project has released several condors in recent years. Chile and Argentina probably have the most condors, though no precise population estimates exist, Jacome said.

Before Egg 54 arrived at the incubation center here about two weeks ago, another egg successfully hatched in late November. That baby condor now lives in a special nursery box fitted with a one-way glass window to prevent the bird from seeing the conservationists.

At feeding time, the workers go one step further to ensure that the bird does not learn to associate survival with humans. The workers put on latex hand puppets that resemble adult condors. Then they reach through an opening near the bottom of the box and stage a puppet show for the baby birds.

Taking care to remain completely silent, program coordinator Vanesa Astore did that one day last week. She manipulated the puppet's beak to playfully peck at the baby condor's down. With the chick distracted, she stealthily placed a meal of rat meat in the cage. About a minute later, the baby frantically gobbled up every trace of the food.

"The puppets are important because they learn to recognize adult condors at feeding time, as they do in nature," Astore said.

After about two months in the nursery boxes, the condors are moved into open areas to socialize with adult condors that have been rescued by the group. One of the adult birds, for example, is a female with a broken wing that was found in Beagle Channel, near the continent's southern tip.

Over several months, the adult birds help teach the young condors how to scavenge carrion. The little ones eventually learn to fly and are released into the wild.

When they reach full size, the birds weigh as much as 26 pounds and have wingspans of more than 10 feet.

All of the released condors -- both those hatched from eggs and those rescued -- are tagged with satellite chips. Every day, Jacome receives e-mails with the Global Positioning System coordinates of individual birds, allowing him to chart their flight patterns on maps.

The images show that most of the birds raised in captivity begin as tentative fliers, venturing only short distances from their primary nesting areas. But after four years, most become what Jacome calls master fliers, capable of covering hundreds of miles.

The satellites also can tell if the birds stop moving, which usually means they've fallen victim to modern threats -- a scarcity of carrion, collisions with high-tension power lines and run-ins with hunters. "If we get a call that a condor is in trouble and we can get there in time, we will rescue it and -- hopefully -- rehabilitate it so it can be reintroduced to nature," Jacome said.