Across much of Latin America, inflation is the top issue

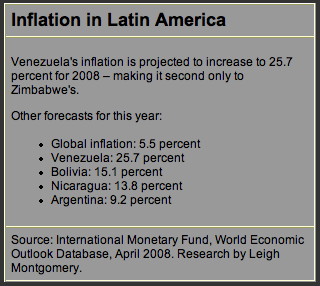

In 2008, Venezuela's inflation rate is projected to be 25 percent -- second only to Zimbabwe's.

May 20, 2008 - Christian Science Monitor

By Sara Miller Llana, Staff writer of The Christian Science Monitor

Buenos Aires - At a take-out restaurant here called Deliverate, where homemade empanadas and quiches line a glass counter, each menu is freshly stamped with a new addendum: "Our prices have gone up 20 percent due to a situation that is public knowledge."

(right) Protest: Planes flew over Salto, Argentina, to show support as farmers began their second strike in two months over higher export taxes on soybeans. (Photo: Natacha Pisarenko/AP)

(right) Protest: Planes flew over Salto, Argentina, to show support as farmers began their second strike in two months over higher export taxes on soybeans. (Photo: Natacha Pisarenko/AP)

"The price of eggs is up;, milk, cheese, meat," says Ricardo Maringolo, the manager of Deliverate. "We had no choice; and we are still losing money. We are not raising our prices as much as prices have risen."

Global price spikes in food and fuel have impacted the entire region, but in pockets of Latin America -- notably Argentina and Venezuela -- double-digit inflation has led to serious questions about their governments' handling of the situation, and the political ramifications are already being felt.

Farmers in Argentina called a second strike in two months over export taxes that their president, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, said were justified to tame inflation. Grocery bills have also gone up in Bolivia and Nicaragua, making waning earning power the top concern of many Latin Americans -- and perhaps the biggest challenge for governments.

"The inflation here is incredible," says Oscar Gill, whose earnings as a taxi driver in Venezuela's capital, Caracas, no longer cover his family's expenses. "I'm middle class, but I feel poor."

Denting presidential support

In the past five years, inflation across Latin America has been largely under control. Even in Argentina, the current, unofficial rate -- estimated by economists to be as high as 25 percent -- is not catastrophic, but could undermine the presidency of Ms. Fernandez de Kirchner, says Federico Thomsen, an economic analyst in Buenos Aires.

(Officially the number stands at 9 percent, but the statistics are widely discredited by independent economists. "The official number doesn't mean that people aren't paying more in the supermarket," Mr. Thomsen says.)

(Officially the number stands at 9 percent, but the statistics are widely discredited by independent economists. "The official number doesn't mean that people aren't paying more in the supermarket," Mr. Thomsen says.)

Fernández de Kirchner's approval rating fell from 42 percent to 30 percent in her first four months in office. Pollsters say her move to raise the tax on soybean and sunflower seed exports to more than 40 percent -- which sparked massive, nationwide strikes -- is to blame. It hurt her government, too: Economy Minister Martin Lousteau resigned in the midst of the crisis.

"Every time we buy less and it costs more," says Patricia Maldonado, a nurse in Buenos Aires, carrying her baby on her hip. "[Fernández de Kirchner] doesn't have to worry about food bills, but we do."

In Venezuela, rising prices -- the average inflation rate from March 2007 to March 2008 was 29.1 percent -- have also hurt President Hugo Chávez's popularity. One poll by Keller & Asociados showed Mr. Chávez's support fell to 37 percent in February from 50 percent in the middle of last year, though other polls show greater support.

Manuel Sutherland, coordinator of the Latin American Association of Marxist Economists, says that the price of food and the scarcity of some products is one reason voters rejected a sweeping referendum in December that would have, among other things, abolished presidential term limits. "Many people associated the socialist changes in the reforms with the scarcity of food, with the queues," Mr. Sutherland says.

He blames a lack of economic activity amid higher demand, and private-sector hoarding of food to influence politics and prices. Teodoro Petkoff, founder of Tal Cual, a newspaper that is critical of Chávez, agrees that oil-driven public spending has increased demand for goods, but says that price controls have aggravated the problem.

The factors influencing inflation are country-specific, and solutions are debated among economists. But Jerry Haar, a professor at Florida International University and coauthor of the new book "Can Latin America Compete?" says it's no coincidence that the countries with the highest inflations are the same left-leaning countries -- Argentina, Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Bolivia -- with high public spending and price controls.

Rosendo Fraga, a political analyst in Buenos Aires, draws a comparison between agricultural powerhouse Argentina and oil-rich Venezuela. Though global spikes in oil and agricultural commodities have been a boon for the petroleum belt of Venezuela and the soybean farms of Argentina, the two fast-growing economies have the region's highest inflation rates. That, says Mr. Fraga, is responsible for the drop in support for both presidents.

'Hemisphere's biggest challenge'

But the impact is more far-reaching. Luis Alberto Moreno, head of the Inter-American Development Bank, told the Miami Herald recently that inflation is "perhaps the biggest challenge in the hemisphere for countries today."

Nicaragua, which is one of the hardest-hit nations with an inflation rate of 17 percent last year -- held a food summit early this month. President Daniel Ortega blamed the crisis on the US and the "tyranny of global capitalism." Venezuela and its allies pledged to create a $100 million food fund.

For now, many countries have, like Argentina, relied on a patchwork of price controls that some embrace and others call "Band-Aid" approaches. President Evo Morales in Bolivia, which reported an annual rate of 11.7 percent in 2007, temporarily prohibited exports of cooking oil last month.

But Napoleon Pacheco, an economist at the Fundacion Milenio in La Paz, Bolivia, says such measures have failed -- and the hardest-hit are the poor. "Inflation has the biggest impact on those with limited resources," says Mr. Pacheco. "In surveys the decreased power of salaries is voters' biggest worry."

• Charlie Devereux contributed to this report from Caracas, Venezuela.