Militarization and the War on Drugs in Peru: Interview with Ricardo Soberón Print E-mail

October 27, 2008 - UpsidedownWorld.org

Written by Yásser Gómez

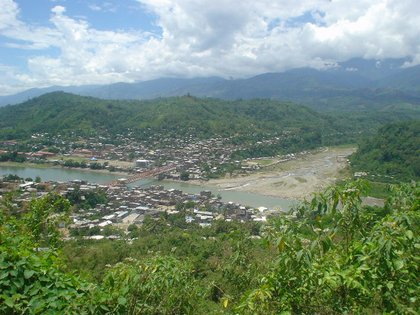

The government of Alan García has initiated Plan VRAE, a military offensive in the South Andean region of Ayacucho, specifically in the Apurímac Ene River Valley (VRAE) with the object of exterminating the surviving militias of the Communist Party of Peru - Shining Path (PCP-SL) and defeating drug trafficking. However, this is occurring precisely at a moment in which more than a hundred North American marines have settled themselves in Ayacucho with ‘humanitarian goals,’ which the population of Huanta took to the streets to reject. The marines’ noble goals were visually contradicted by their armed arrival in military helicopters on low level flights. Huamanga, the capital of the region of Ayacucho would be a strategic place to place a new US military base in South America to replace the one in Manta, Ecuador. To discuss this theme, Upside Down World interviewed Peruvian lawyer Ricardo Soberón Garrido, a specialist in militarization and drug issues and an investigator for the Transnational Institute (TNI). Soberón has studied International Politics and Security at the Univeristy of Bradford, England, and has published books including Hablan los diablos. Cuatro ensayos sobre políticas de drogas [The Devils Speak: Four Essays about Drug Politics] and Asilo y Refugiados en las fronteras de Colombia [Asylum and Refugees on the Colombian Borders]. (Photo: VRAE)

The government of Alan García has initiated Plan VRAE, a military offensive in the South Andean region of Ayacucho, specifically in the Apurímac Ene River Valley (VRAE) with the object of exterminating the surviving militias of the Communist Party of Peru - Shining Path (PCP-SL) and defeating drug trafficking. However, this is occurring precisely at a moment in which more than a hundred North American marines have settled themselves in Ayacucho with ‘humanitarian goals,’ which the population of Huanta took to the streets to reject. The marines’ noble goals were visually contradicted by their armed arrival in military helicopters on low level flights. Huamanga, the capital of the region of Ayacucho would be a strategic place to place a new US military base in South America to replace the one in Manta, Ecuador. To discuss this theme, Upside Down World interviewed Peruvian lawyer Ricardo Soberón Garrido, a specialist in militarization and drug issues and an investigator for the Transnational Institute (TNI). Soberón has studied International Politics and Security at the Univeristy of Bradford, England, and has published books including Hablan los diablos. Cuatro ensayos sobre políticas de drogas [The Devils Speak: Four Essays about Drug Politics] and Asilo y Refugiados en las fronteras de Colombia [Asylum and Refugees on the Colombian Borders]. (Photo: VRAE)

UDW: What is your analysis of the War on Drugs directed by the US and the Peruvian government?

ImageRSG: In 1989, this War on Drugs was started, promoted by President George Bush Sr, and in 1998 the international community decided to establish some very concrete goals to achieve a reduction in the sale and demand [of illegal drugs]. In 2008 and 2009 begins the process of evaluation and reflection undertaken by the international community to see how much has been achieved in a decade. The truth is that it has been a failure from every point of view. In light of its focus, the unachieved goals, the collateral damages, this war hasn’t had a single positive return. In terms of the goal of getting rid of a drug war, if you look at the fact that the majority of the fight has been directed against the most vulnerable sectors, like the campesino producers, consumers, microcommercializers, and you admit that the economic system co-exists with the drug trafficking lords in money laundering, this is clear evidence of the small success of the focus of reducing the supply of drugs. Moreover, they now just checked that between the years of 2000 and 2005, the US placed $4,726,000,000 dollars for the fight against drugs in the goal of Plan Colombia. They’ve fumigated 866 thousand hectares of land and they haven’t been able to stop or slow the supply of cocaine. Cultivation levels have stabilized, when they haven’t risen, they’ve dispersed to different departments of Colombia.

In the case of Peru, even if the amounts haven’t been the same, obviously, the War on Drugs has had another kind of failure: the US supported, sustained and reaffirmed the dictatorship of Alberto Fujimori, as well as Vladimiro Montesinos, knowing the clear relationships between Montesinos and drug trafficking, and let them be. This proves that, for the US, the true fundamental objective is not the War on Drugs, but that this is a justification for superior interests: the control of territory, natural resources, military presence and the sustenance of political regimes that are useful and functional for the Departments of State and Defense. The collateral damages are evident: the judicial system, democracy, the environment, and social security. All are elements that have suffered the consequences of a war that is impossible to fight and, moreover, impossible to win.

UDW: Does the Apurímac Ene River Valley (VRAE) Plan have the same objective as Plan Colombia or Plan Mérida? How much is it advancing? Does it have economic support, or is it just one more bluff from Alan García’s administration?

RSG: The Plan VRAE was initiated at the end of Alan Wager’s management (2007) as the Defense sector’s attempt to make presence in a strategic zone like in the Apurímac –Ene River Valley. This is a region that has suffered from a persistent absence of the state, as much economically and politically as judicially, and this has meant that the colonization promoted in the decades of the sixties and seventies was fundamentally focused toward the economy of illicit drug trafficking. The Defense Department’s intent to create a presence there clashed with the previsions of the North American State, those of DEVIDA (National Commission for Development and Life without Drugs), which is the local entity charged with executing the funds coming from the cooperation of the US.

[Plan VRAE] has definitely not been more than a bluff, one that has implicated the realignment of the budget games of the sectors like transportation, health, education or production, aimed at presenting Plan VRAE as a management initiative and promotion of development on the part of the Peruvian State, something that has not happened. Plan VRAE has not made presence in the zone, it are not recognized by the population, which has not been consulted about its actions.

Plan VRAE has a similar format to the Plans Mérida, Colombia, Plan Puebla Panamá. For the population, seeing artillery helicopters that come and ‘bring development’ is not a good image, though this is what the government of president Alan García and the administration of the Defense Ministery, presided over by Antero Flores Araoz has expressed and reflected about what Plan VRAE means. I’m afraid that far from resolving the problem, Plan VRAE is going to provoke greater problems and distrust in the region. In circumstances in which the remnants of the Peruvian Communist Party – Shining Path (PCP-SL) are a completely different entity than the entity we knew before, under the leadership of Abimael Guzmán (today in prison). It’s an entity very joined to economic activities, with capacity of territorial manipulation and control, and therefore strongly linked to the organized trafficking rings, who charge quotas on legal and illegal activities like hydrocarbons, forest industry and contraband. And it allows them to take the advantage of all of the shortcomings and omissions that the Peruvian State incurs at the moment of creating a presence in the VRAE. So therefore, I don’t expect the Plan VRAE to accomplish anything.

(below) Peruvian Armed Forces destroying coca processing pits in the VRAE [Photo: Peruvian Ministry of the Interior]

UDW: Why is it in the geopolitical interest of the US to have military bases in Peru?

RSG: First, to make a security circle around the armed conflict in Colombia. Second, put a wall of contention against the advance of the Bolivarian project in South America. In the third place, to confront the Brazilian model of security of protection and property over the Amazon, and finally, the appropriation of territory with the goal of exploiting natural resources. These are the four axes on which we need to analyze the current North American military deployment in Latin America. Maybe there is a fifth to look for, which could be the growing influence of Russia and China in matters having to do with international, energy and military cooperation in countries like Venezuela and Bolivia, if a kind of Cold War or regional character scenario develops in South America and North American interests are in tension with those of the Chinese and Russians.

UDW: What panorama do you have about the supposed military bases installed in the cities of Chiclayo and Huamanga?

RSG: The most complicated part is that the US hasn’t resolved how to replace Manta. It had the possibility of moving it to Colombia, but in reality no section of Colombian territory resolves Southern Command’s strategic problem of having a satellite control and aerial monitoring of the western hemisphere, of the coast of the South Pacific, from Buenaventura, Colombia, to Valparaíso, Chile. Only Peruvian territory offers this. All of the attempts that have been planned, and the military exercises like UNITAS, Panamax, Nuevos Horizontes that are being executed are, according to my judgment, attempts by the Armed Forces of both countries to study the strategic, political and social conditions on which a military installation could be confirmed. Until now, nothing has worked, in terms of there being a relative political and social opposition to the idea, but the judiciary framework is there, the political will of the Alan García administration and the North Americans continues. And, in the moment that we neglect ourselves and allow this to happen, they’ll enter there. In fact I am afraid that US installations like Palmapampa in Ayacucho, Mazuco in Puno, Santa Clotilde in Iquitos, Mazamari, Santa Lucía and Ancón are effectively available. I am sure that the consulting group of the North American army that is attached to the US embassy in Lima, has an enormously strong relationship with their counterparts in each one of the these installations, and I’m not talking about at the operative level of captains and seniors. That’s the situation; those are the conditions, the scenarios. What we need to do is to be attentive to blocking it or, if we find out about a specific plan, we need to raise it up and make it public.

Yasser Gomez is a journalist, Upside Down World correspondent in Peru and editor of Mariátegui. La revista de las ideas. [The Magazine of Ideas]. yassergomez(arroba)gmail.com