Is it a foolish infatuation or a great love story?

Sunday, October 7, 2007, Washington Post, Page BW15

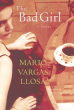

The Bad Girl

The Bad Girl

By Mario Vargas Llosa

English-Translated from the Spanish by Edith Grossman

Farrar Straus Giroux. 288 pp.

ISBN-10: 0374182434 (hb Oct 2007) $25

Amazon.com: $14.99

ISBN-10: 0571239331 (pbk due UK Jan 2008) £12.99

Travesuras de la nina mala

Travesuras de la nina mala

By Mario Vargas Llosa

Spanish

Alfaguara. 376 pp.

ISBN-10: 9707704667 (pbk May 2006) $19.95

Amazon.com: $13.57

Reviewed by Jonathan Yardley (English edition Oct 2007)

Mario Vargas Llosa's perversely charming new novel isn't among his major books -- it lacks the depth of Conversation in the Cathedral, Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter or even the more recent and less successful The Feast of the Goat-- but it is irresistibly entertaining and, like all of its author's work, formidably smart. Its story of romantic and sexual obsession is characteristic of Vargas Llosa, as are its two principal characters: the narrator, Ricardo "Slim" Somocurcio, an amiable man whose ambitions extend no further than "a nice steady job that would let me spend, in the most ordinary way, the rest of my days in Paris," and the woman -- we don't know her real name until a few pages from the end -- whose "indomitable and unpredictable . . . personality" wholly captivates him.

It is commonly assumed that Vargas Llosa's male protagonists are autobiographical, as often is obviously the case, but resemblances between him and Ricardo Somocurcio pretty much end with their mutual admiration of women and vexation over Peruvian culture. Ricardo's lack of drive, on the other hand, scarcely mirrors his creator's powerful ambition. American readers may not fully appreciate what a force Vargas Llosa is in his native Peru, where he spends about a quarter of each year. He enjoys a prominence -- literary, social, cultural, political -- that no American writer could dream of achieving. Not only is he by far Peru's best known writer, of fiction and nonfiction, he also writes a regular, highly influential column for El Comercio, the country's premier newspaper, he was a serious candidate for the presidency in 1990 (he was defeated by the now disgraced Alberto Fujimori), and he is a familiar, adored figure to millions of Peruvians.

In the world at large he is known as one of the leading writers in the Latin American literary "Boom," his acclaim today probably exceeded only by that lavished upon Gabriel García Márquez. That he has not been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature is nothing short of scandalous, especially in light of the many nonentities to whom the prize has gone in recent years, but this says more about the Swedish Academy than it does about the work of Vargas Llosa. Doubtless the prize went to García Márquez on merit, but doubtless as well his cozy relationship with Fidel Castro helped his cause; Vargas Llosa by contrast is of a more conservative persuasion, and this the complacently ideological Swedes do not countenance, much less honor.

The Bad Girl will do nothing to improve his lot in Stockholm, but somehow it seems unlikely that this much worries Vargas Llosa. Obviously, the novel was written for the sheer fun of it -- the fun for Vargas Llosa in writing it, the fun for us in reading it. It also obviously was written out of a deep nostalgia for the author's lost youth and for the Lima in which he then lived. He evokes it beautifully:

"In the early years of the 1950s there were still no tall buildings in Miraflores, a neighborhood of one-story houses -- two at the most -- and gardens with their inevitable geraniums, poincianas, laurels, bougainvilleas, and lawns and verandas along which honeysuckle or ivy climbed, with rocking chairs where neighbors waited for nightfall, gossiping or inhaling the scent of the jasmine. In some parks there were ceibo trees thorny with red and pink flowers, and the straight, clean sidewalks were lined with frangipani, jacaranda, and mulberry trees, a note of color along with the flowers in the gardens and the little D'Onofrio ice-cream trucks . . . that drove up and down the streets day and night, announcing their presence with a Klaxon whose slow ululation had the effect on me of a primitive horn, a prehistoric reminiscence. You could still hear birds singing in that Miraflores, where families cut a pine branch when their girls reached marriageable age because if they didn't, the poor things would become old maids like my aunt Alberta."

Into this paradise, during the "fabulous summer" of 1950, comes a 14- or 15-year-old girl who calls herself Lily and claims to be Chilean. Soon enough she is found out as an impostor and expelled from 15-year-old Ricardo's privileged set, but the damage has been done: He is madly in love with her, and her expulsion is "the beginning of real life for me, the life that separates castles in the air, illusions, and fables from harsh reality." She has rejected his declarations of love, but she scarcely vanishes from his life. By the early 1960s he is in Paris, studying (successfully) to become a translator at UNESCO, when she appears as Comrade Arlette, ostensibly to bring Castroite revolution to Peru. She goes off to Cuba, but soon resurfaces as Madame Robert Arnoux, wife of a French diplomat. Ricardo craves her as ardently as ever, even as she blithely dismisses him: "What cheap, sentimental things you say to me, Ricardito." She does permit him to make love to her but vanishes once more, reappearing as Mrs. Richardson, wife of a wealthy Englishman hooked on "the aristocratic passion par excellence: horses."

By now Ricardo has figured out that she has come a long way: "I tried to picture her childhood, being poor in the hell that Peru is for the poor, and her adolescence, perhaps even worse, the countless difficulties, defeats, sacrifices, concessions she must have suffered in Peru, in Cuba, in order to move ahead and reach the place she was now." He understands that she is now "a grown woman, convinced that life was a jungle where only the worst triumphed, and ready to do anything not to be conquered and to keep moving higher." And yet:

"Everything I told her was true: I was still crazy about her. It was enough for me to see her to realize that, despite my knowing that any relationship with the bad girl was doomed to failure, the only thing I really wanted in life with the passion others bring to the pursuit of fortune, glory, success, power, was having her, with all her lies, entanglements, egotism and disappearances. A cheap, sentimental thing, no doubt, but also true that I wouldn't do anything . . . but curse how slowly the hours went by until I could see her again."

Over and over again she tests him, never more so than in a bedroom in Tokyo, "an experience that had left a wound in my memory." He actually manages to persuade himself for a time that he does not love her, but the obsession is too powerful: "I was a hopeless imbecile to still be in love with a madwoman, an adventurer, an unscrupulous female with whom no man, I least of all, could maintain a stable relationship without eventually being stepped on." In time he tells his story to a friend, a woman, who calls it "a marvelous love story," and who later adds, "What luck that girl has, inspiring love like this." There is a moment when Ricardo wonders, "Could this farce more than thirty years old be called a love story, Ricardito?" but in his heart he knows that's just what it is, and Vargas Llosa tells it as such.

Being Vargas Llosa, he takes care of plenty of other business as well. The novel touches on the full sweep of Peruvian history from the 1950s to the Shining Path terrorism, "which would last throughout the eighties and provoke an unprecedented bloodbath in Peruvian history: more than sixty thousand dead and disappeared." He says a lament for the generation of Peruvians before his own "who, when they reached old age, saw their lifelong dream of Peru making progress fade instead of materialize."

He also, having made Ricardo a translator and interpreter, affords himself the opportunity to have a bit of fun. One interpreter remarks: "Our profession is a disguised form of procuring, pimping, or being a go-between," and when Ricardo himself turns to translation, he discovers that, "As I always suspected, literary translations were very poorly paid, the fees much lower than for commercial ones." Probably no one is more amused by this than the redoubtable Edith Grossman, who has translated The Bad Girl with her accustomed skill and grace, making this lovely novel wholly accessible to American readers.

Jonathan Yardley's e-mail address is yardleyj@washpost.com.