(above) Roberto Penny Cabrera examines fossilized whale remains in the Ica Desert of Coastal Peru. (photo: Susana Raab for The New York Times)

Out of the Desert and Into the Rain Forest

July 13, 208 - New York Times

By GREGORY DICUM

THIS is not how one thinks of Peru. I opened my eyes without moving on the soft desert floor. A perfect orange sun was rising over a distant ridge, its undulations mirroring the mound where I had rolled out my sleeping bag the night before. My ears hummed in the silence. All around me, in dawn-lighted tans, whites and stripes of purple and orange, wind-sculptured forms extended in the limpid desert air. I saw no people; no signs of life at all.

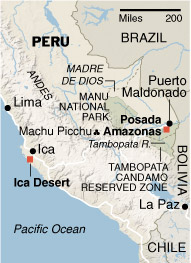

(left) map

(left) map

All of Peru’s coast is arid, but south of Lima it becomes profound. It is one of the driest places on earth, the desolation is broken here and there by verdant valleys where streams venture seaward from the distant Andes.

Almost half of all visits by foreigners to Peru include a stop at Machu Picchu, and with good reason — the ancient Inca site is spectacular. Yet the country is far more than a one-hit wonder. The geography that gave rise to numerous ancient civilizations — dry coast, a backbone of high mountains and tropical rain forest in the east — endows the country with unparalleled natural areas.

And many are accessible, easy to add to an Inca heartland trip. In February, I visited two of Peru’s extremes — the desert and the rain forest. (The third extreme — the snow-capped high Andes — I left for another visit.)

My desert guide was Roberto Penny Cabrera. A former Peruvian marine officer and a mining engineer, Mr. Cabrera cuts a dashing figure in tan fatigues with a long knife strapped to his waist. “You like my knife?” he asked when we met in the lovely, dune-rimmed oasis of Huacachina. “Wait until you see my truck.”

Before long we were roaring out into the desert in said truck — a Mad Max pickup in olive drab, crammed with provisions: two spare tires, extra diesel and lots of water (including for a shower that protrudes from the vehicle’s side). Once we were off the paved road, it was hard driving, bouncing in the heat beneath stark hills. In February, the noon sun bears down from directly overhead, erasing any possibility of relief. Most signs of life are just as much signs of death: old burial grounds, ancient mummies and the bleached bones of what Mr. Cabrera said were failed adventurers.

Indeed, the most abundant creatures in the Ica Desert died millions of years ago: the area was once a shallow coastal shelf, and eons of wind have revealed rich fossils. Shark teeth lie in gravel-strewn gullies, or sticking straight out of sand-smoothed walls. These especially are Mr. Cabrera’s driving passion, and a sort of fever grips him when he finds a good hunting ground.

Fossils are consumed by the wind as well. But in a few places — known only to those who, like Mr. Cabrera, can read the landscape — complete whale skeletons lie undisturbed on the desert floor. They rest slumped but whole, tragic marine forms where the very idea of swimming seems absurd.

Some are so well preserved they include fossilized skin and even baleen. One whale skull had been opened by the wind to reveal the opalized remains of the animal’s brain, glowing in the sun as a reminder that all we animate today is borrowed from mute stone.

The Peruvian desert is among the best fossil-hunting grounds in the world, yet it has received little protection. Most of the land is leased as mineral concessions, and the city of Ica does not have a single museum dedicated to the fossils. Unregulated fossil hunters operate with impunity.

“They are rapers!” bellowed Mr. Cabrera when we came across a fossil dig of dubious authority. “Fossils belong to the ground!” As we poked around the area, I found the stupendous remains of a long-toothed dolphin and felt some of Mr. Cabrera’s fever.

The desert rewards those willing to put up with some hardship. The second time the radiator blew, the mercurial Mr. Cabrera fell into a funk, and I found myself sitting by the campfire, seriously evaluating whether I would survive a nighttime escape attempt.

My fidelity was rewarded with an early-morning walk looking for shark teeth with Mr. Cabrera. We found them before long: white ones, yellow ones and brown ones, imbued over millions of years with the color of the sediment that held them.

It was like beachcombing the ages: there is a stingray spine, and here a lobster shell. This is a bone from a seabird, and that a sea urchin and some petrified wood. And then, in a wind-scoured gulley, Mr. Cabrera spotted an unmistakable glint: a five-inch tooth from a megalodon — the extinct whale-eating giant shark. He did a dance, kicking up soft dust that hung in the warming air and stopping only to show me his forearm speckled with goose bumps. “Perfect things like this are a message from Pachamama,” he said, referring to the ancient Andean earth goddess..

That night I slept on the desert floor next to the exposed 12-million-year-old remains of a whale, its pearly ribs by my head. I gazed up at the outrageous southern stars—the Milky Way so vivid it no longer seemed an unlikely home for such creatures.

A few days later, it was all obscured by riotous life. I was in the rain forest, at Posada Amazonas, a lodge along the Tambopata River in the Peruvian Amazon. Water, the handmaiden to life, was everywhere: in the chai-colored river, in the humid air and dripping from leaves onto muddy trails. Intricate and fantastical diversity — immense trees to tiny, perfect insects — was all around us.

The Peruvian region of Madre de Dios is undergoing an eco-tourism boom. More than 70 jungle lodges cater to visitors eager for an easy visit to the pristine Amazon. The protected areas there include Manu, a vast park that falls down the eastern slope of the Andes into primordial rain forest, and Tambopata, which together with an adjacent area in Bolivia, is larger than Connecticut and comprises the biggest chunk of protected forest in the Amazon basin.

The second order of business upon arriving at Posada Amazonas, after being issued rubber boots, is a short walk down a forest trail to the lodge’s canopy platform. The 120-foot climb brought our small group of visitors to the light, fragrant air of rain forest treetops. We looked over a sea of trees cataloging the entire range of green shapes: tufts, sprays, bursts, blazes, cascades and starbursts. It seemed an aerial coral reef as multitudinous birds (a toucan, a blue-headed macaw, a guan) sought roosts in huge crowns, some aflame with blossoms, others bearing heavy pods of Brazil nuts.

The river bent far below, and the foothills of the Andes floated on the horizon. The sunset cut a tracery of branches in the still, spiced air, exciting a billion cicadas.

The lodge itself is spacious and comfortable. High thatch roofs shelter big, airy dining and sitting areas. Rooms, connected by elevated wooden boardwalks, provide unexpected comfort — mosquito nets, showers and flush toilets — without separating guests unduly from the rain forest; one side of each room is open directly into the unrelenting greenery.

At Posada Amazonas, each party of visitors is assigned a guide. Rodolfo Pecha, our guide, is a member of the Ese’eja indigenous group from the community of Infierno, which owns the pristine forest around the lodge. In a partnership, Rainforest Expeditions, the company that operates the lodge, is leasing the land for 20 years while training community members to take over its operation.

To Mr. Pecha, the forest din is an intelligible language. Often, he would stop us on the trail, picking out a few notes from the sibilant cacophony of chirps, barks, honks, buzzes and hoots. Then he’d answer. “That’s an antbird,” he’d say between rising whistles. “They’re really beautiful.” He’d creep off into the dense underbrush, binoculars at the ready, trailing considerably less graceful visitors through the vines.

On our second day, we awoke before dawn to the alarmingly throaty din of howler monkeys. After a quick breakfast of strong Peruvian coffee and fresh fruit, we made our way by river and squelching, muddy forest trail to an oxbow lake — a curving stretch of perfectly flat water cut off when the Tambopata meandered elsewhere.

We floated out on a silent pontoon boat, emerging into dawn light. Cascades of pink trumpet flowers dripped into the syrupy brown stillness. All around us, life was under way: dozens of birds, from waterfowl like tropical cormorants and kingfishers, a fine-feathered tiger heron and a gangly osprey, to beasts like the hoatzin. Turkey-like things as imagined by Dr. Seuss, hoatzins cruised the shrubbery along the water’s edge, eating leaves and grunting contentedly.

A riotous flock of parakeets passed overhead, heralding a trio of giant river otters that furrowed the lake in their hunt for breakfast. Easily the size of tall, skinny people, the otters are skittish and severely endangered, yet they seemed comfortably at home, gliding playfully and coming close enough for us to see their sharp teeth and button noses.

Our boat that morning had a jolly crew of nature lovers: a pair of American birders, a Hungarian couple and a Brazilian couple. They were the sort of people who don’t mind a little sun and a few mosquitoes if it means glimpsing a troupe of dusky titi monkeys. One morning on the trail, I came across the Brazilian couple gamely eating live termites at the suggestion of their guide. “Spicy,” they said, offering me one.

At the edge of the river Gyorgy Valyi, one of the Hungarians, sank up to his thighs in quicksand and surely would have been reclaimed by the preposterous Amazonian hazard had not a handful of guides rushed to the rescue. Even as he was sinking, Mr. Valyi had a grin of delighted disbelief, as though finding himself in a Tintin adventure.

Later that night, as I lay in bed, I too felt as though I were sinking into the living forest. The wafting perfumes and strange growls melded into a baroque stereoscopic vision — dreams of the hidden landscape underlying life itself.

IF YOU GO

GETTING THERE

Round-trip flights between Lima and Kennedy Airport in New York start at about $600 for travel in September. American and LAN Peru have direct service. From Lima, a bus to the city of Ica is about $20. Round-trip flights between Lima and Puerto Maldonado in the Amazon start at $210 on Lan Peru.

GETTING AROUND

The latest “Moon Handbook to Peru” (Avalon Travel, 2007; www.moon.com) is useful in planning a trip that includes classic sites like Machu Picchu as well as excursions way off the beaten track. Outfitters and tour organizers routinely cite prices in United States currency.

The desert adventurer Roberto Penny Cabrera can be reached at icadeserttrip@yahoo.es or by telephone at (51-56) 956-624-868. His Web site is www.icadeserttrip.com. Two-day trips start at $300 for one or two people.

WHERE TO STAY

Information on Posada Amazonas, the eco-lodge in Madre de Dios, is available from the United States at (877) 870-0578 or at www.perunature.com/pages/pa_about1.htm. Three-day two-night programs start at $295 a person for double occupancy.