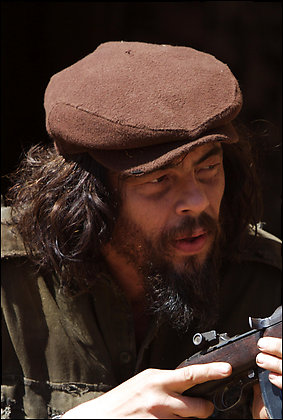

(above) Benicio Del Toro is mesmerizing as revolutionary

Che Guevara.( Camera Works Photo Credit: By Teresa Isasi -- Ifc Films Photo)

'Che': A Vivid Portrait Of a Charismatic Man

January 16, 2009 - The Washington Post

The best way to encounter "Che," Steven Soderbergh's four-hour, Spanish-language epic about guerrilla leader Che Guevara, is to let go of words like "film" and "movie," words that somehow seem inadequate to the task of describing such a mesmerizing, fully immersive cinematic experience.

In this sprawling yet surprisingly taut retelling of Guevara's life during the Cuban revolution and his ill-fated attempt to bring the fight to Bolivia, he comes into sharp, sympathetic focus, by way of an extraordinary performance by Benicio Del Toro. By the end of "Che," viewers will likely emerge as if from a trance, with indelibly vivid, if not more ambivalent, feelings about Guevara than the bumper-sticker image they walked in with.

"Che: Part I" gets underway in Mexico City in 1955, when Raul Castro first introduced Guevara to his brother, Fidel. After a dinner discussing Cuba's grinding poverty, illiteracy and poor health care, Guevara signs on with the brothers, convinced that armed struggle is the only way to topple the oppressive order.

Working from a script adapted from Guevara's own diaries, Soderbergh plays it utterly straight, delivering his story in episodes that are gratifyingly free of starchy speechifying and weighty exposition. It's a lucid visual style suited to a man who never doubted his own motivations or violence as a means to realize them.

When "Che: Part II" begins, it's 1965. Guevara travels to Bolivia, where he's confronted by well-trained military opponents aided by Vietnam-tested U.S. advisers. Even the landscape seems to have turned against Guevara, who makes his wheezing, asthmatic way to capture and execution as if in a death foretold.

True to his restrained, unemphatic style, Soderbergh resists all calls to melodrama during Guevara's final moments. Still, from scenes of Guevara insisting that new recruits learn to read, to Del Toro's unfailingly gentle portrayal of a man in love with "humanity, justice and truth," their Guevara turns out to be much closer to the humanist martyr of Alberto Korda's iconic photograph than the man known as a murderer by his detractors.

Soderbergh has created an absorbing, even hypnotic cinematic experience in "Che," which for all the depth and detail of its portrayal of a man, turns out to be a stirring homage, not just to its subject, but to the trials and glories of filmmaking itself.

-- Ann Hornaday