Photo Gallery: 16 Carnival Slides

Llamas bleed, devils dance at Bolivian Carnival

February 22, 2009 - Reuters

By Fiona Ortiz

ORURO, Bolivia (Reuters) - In a Bolivian Carnival tradition, dozens of howling-drunk miners cut the hearts from four trussed-up llamas in a dark mine tunnel lit by a bonfire, accompanied by the deafening blare of a brass band.

"It's good luck," proclaimed Quechua Indian witch doctor Jose Morales, holding up a beating llama heart while miners streaked blood on their faces to ward off hazards in the Itos mine above the central Bolivian town of Oruro.

"All four hearts were beating when they came out; that means the year will go really well. It's a very good sign," miner Isaac Meneses said with relief.

Sacrifices to appease "Uncle," the capricious spirit who owns the silver, tin and zinc deposits in the Bolivian Andes are a key ingredient to Carnival celebrations this week.

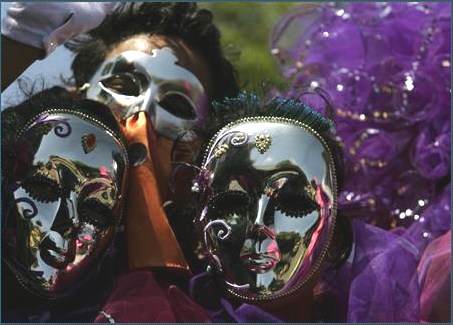

So are heavy drinking, gorgeously attired carnival queens in thigh-high golden platform boots, water-pistol battles, exploding firecrackers and columns of dancers in fantastic masks leaping through colored smoke.

Boisterous partying and religious fervor mingle in Bolivia's biggest Carnival celebration in Oruro, a mining and commercial city of more than 200,000 people at the heart of South America's poorest country.

The passion of Friday's llama sacrifices spilled over into Saturday's parade, where hundreds of dancers donned out-sized

devil masks representing the spirit of the mine.

Crowds of tourists from North and South America and Europe cheered the exhausted dancers along the four-hour parade route, which ends with participants on their knees before a shrine to the Virgin Mary in a Roman Catholic church.

"It's total euphoria, adrenalin. You can feel the vibes from the crowd and hear the rattles and the drums. When the television cameras focus on you know everyone in Bolivia is watching," said Cecilia Aguilar, a 25-year-old economist who dances in the Sambos Caporales de la Paz troupe.

Aguilar pledged to dance for three years in return for a favor from the Virgin Mary. For months before Carnival her troupe gathered to pray and to practice.

SWELLING INDIAN PRIDE

Most tourists come for the Saturday parade, paying $15 to $100 each for seats on bleachers along the route.

But a resurgence in Bolivian Indian pride swelled participation in a lesser-known parade, held two days earlier, when 119 troupes from indigenous communities stomped and swirled through Oruro.

Instead of sequins and masks, they wore traditional skirts and shawls, played Andean flutes, and carried sheaths of sorghum and alfalfa.

President Evo Morales, an Aymara Indian who is the country's first indigenous president, joined the dancing. Orurans say the Indian element of Carnival has intensified since he took office three years ago.

"Now that we're in power we put more energy into it; no one is ashamed anymore to wear Indian costumes," said Berto Caceres, 43, a local politician and miner, whose daughter, a law student, was among the dancers.

Most Bolivians are Indians, but they are still struggling to emerge from centuries of discrimination that began with their enslavement in mines.

Oruro was long ago abandoned by big mining companies but low-budget groups of laid-off miners still work the mostly depleted mines in the hills that rise above the parade route.

They earn up to $300 a month, decent money in Bolivia, but the drilling and dynamite are dangerous and three miners have died in the Itos mine since 2001.

That's why they gather every year during Carnival to spill llama blood down the shafts.

"Sure I feel bad for the llama, but better he dies than us. If we don't feed Uncle, he'll eat us. We're spilling the blood so we don't have accidents," said miner Jaime Robles, 51, a big wad of coca leaves stuffed in his cheek.

(Editing by Terry Wade and Eric Walsh)