(above) Mount Illimani looming over the village of Khapi. Many believe Mt Illimani will have completely lost its glaciers in a few decades (Photo: Mark Chilvers)

Bolivia’s Indians feel the heat

July 29, 2009 - BBC News

By James Painter, BBC News, Khapi, Bolivia

Marcos Choque is a 67-year-old Aymara Indian with holes in his trousers and battered sandals. He appears remarkably cheerful.

Sitting among his fellow villagers from Khapi, perched high up in the Bolivian Andes, he seems to delight in cracking jokes.

But ask him about Illimani - the 6,400m (21,000-ft) mountain that towers above his village - and his mood turns more sombre.

"When I was young, the snow often came down as far as there," he says, pointing to the hills. "But in the past few years, the snow-line has risen 500m. It's getting hotter, which is melting the mountain."

Mr Choque and the 40 families that make up his community have been watching Illimani with increasing alarm. They depend on it for part of their water supply - both to drink and to irrigate their small, terraced parcels of land.

"We calculate that there will be no snow or ice left on Illimani in the next 30 or 40 years. It will be black, or what we call peeled of its whiteness," he says.

Water supply worries

The glaciers on Illimani are estimated to have been there for thousands of years. Its white peaks tower over the nearby city of La Paz, Bolivia's administrative capital.

Many of La Paz's residents swear the snow-line is gradually creeping upwards.

Some were shocked when a newspaper recently published a photo of what Illimani could look like in 2039 - with no sign of any whiteness on top.

Some were shocked when a newspaper recently published a photo of what Illimani could look like in 2039 - with no sign of any whiteness on top.

Hydrologists from La Paz are planning to measure the glacial loss of the mountain. They already know that the nearby glacier of Mururata has lost more than 20% of its surface area since 1956 due to higher temperatures, and probably a greater percentage of its volume.

Earlier this year, the Paris-based Development Research Institute (IRD) estimated that the glaciers in the Cordillera Real mountain range in Bolivia, of which Illimani forms a part, had lost more than 40% of their volume between 1975 and 2006.

The IRD said that the volume had remained pretty constant until 1975, but had diminished quickly since then.

If this tendency continued, the IRD said, it could have a very negative impact on the water supply in the dry season to some cities like La Paz.

Unpredictable

In the case of Khapi, the water from Illimani plays a crucial role in the life and religious beliefs of the community.

Every September, they carry out a ritual, involving offerings called Waxt'a in Aymara. This includes the sacrifice of a llama and other offerings like coca leaves, alcohol and cigarettes to Illimani.

They go through the elaborate ceremony so that, in their words, "Illimani gives them water through the year".

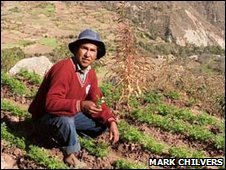

(right) 18-year-old Rogelio Churqui Quispe from Khapi tends his plot of parsley. For Khapi residents such as Rogelio, Mt Illimani is a lifeline Photo: Mark Chilvers

(right) 18-year-old Rogelio Churqui Quispe from Khapi tends his plot of parsley. For Khapi residents such as Rogelio, Mt Illimani is a lifeline Photo: Mark Chilvers

The villagers think that the snow and ice from Illimani accounts for up to half of their annual water supply, although they are not sure.

Bolivian scientists are trying to answer the crucial question of just how much of the water comes from glacial melt at different times of the year. Precipitation and underground aquifers provide the rest.

The more immediate concern of the villagers is the changing climate. They say there is no longer any predictability about when the rains come, compared to the past. And they are sure that there is less rain, and that the weather is getting hotter.

Theirs is not the international language of global warming and carbon emissions.

"Our weather is coming up from where it used to be further down," says Severino Cortez, a community leader, pointing down the mountain from Khapi, which is 3,600m high.

Not everything is bad news. The warmer temperatures mean that some of them can now grow peaches and maize where previously they could not.

Vulnerable

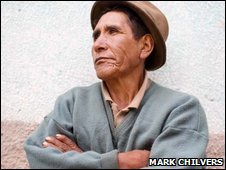

But the Khapi villagers are very worried for the future. "I am getting old," says Marcos Choque.

"I am not going to see Illimani melting away completely, but the young will."

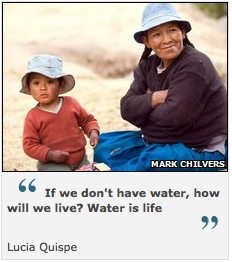

Lucia Quispe, a 38-year-old mother of three, wonders where the water will come from to irrigate her plot of land, where she grows potatoes, maize and beans.

"I am sad and very worried when I think about the future of my children," she says. "If we don't have water, how will we live? Water is life."

(right) 67-year-old Marcos Choque. Marcos Choque fears his children will see Illimani bare of glaciers (Photo: Mark Chilvers)

(right) 67-year-old Marcos Choque. Marcos Choque fears his children will see Illimani bare of glaciers (Photo: Mark Chilvers)

Non-governmental organisations working with Khapi and other nearby communities high up in the Andes say it is particularly unjust that Aymara villagers will suffer the fall-out from global warming when they are amongst the least responsible for it.

Some of the communities are active members of a new civilian pressure group formed this year, called the Platform of Civil Society against Climate Change.

One of the Platform's demands is for the formation of an international tribunal on climate justice, and for an international compensation fund for victims of climate change.

"What's happening at Khapi is typical of what hundreds of poor, indigenous and vulnerable communities throughout Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador are facing," says Juan Carlos Alurrade, executive director of Agua Sustentable (Sustainable Water), which is helping communities to adapt to climate change.

"They depend on glacial melt for irrigation, but the glaciers are doomed."