Lithium for 4.8 Billion Electric Cars Lets Bolivia Upset Market

December 7, 2009 - Bloomberg.com

By Michael Smith and Matthew Craze

Dec. 7 (Bloomberg) -- The wind whips across a 3,900-square- mile expanse of salt on a desert plateau in Bolivia's Andes Mountains. Plastic washtubs filled with an emerald-colored liquid rich in lithium dot the Uyuni Salt Flat, all the way to the volcanoes on the horizon.

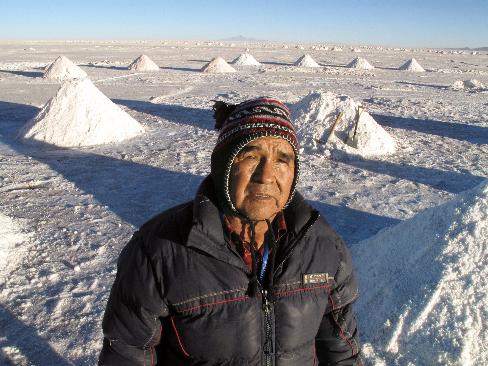

Waist-high slabs of salt are piled around a pond that's shimmering in the sun. Francisco Quisbert, an Indian peasant leader known as Comrade Lithium, sits inside a crumbling adobe building on the edge of the desert. He's explaining how Bolivia, South America's second-poorest country, will supply the world with lithium, which will be used in batteries that power electric cars.

"We have this dream," Quisbert, 65, says. "Lithium could bring us prosperity."

The world's largest untapped lithium reserve -- containing enough of the lightest metal to make batteries for more than 4.8 billion electric cars -- sits just below Quisbert's feet, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

The automobile industry plans to introduce dozens of electric models with lithium batteries in the next three years. Bolivian President Evo Morales says his country can become one of the world's biggest suppliers of lithium, making the nation of 10 million people a major player in the drive to cut the use of fossil fuels.

Even with its massive reserves, Bolivia has never built a lithium mine.

‘Lithium Is the Hope'

"Lithium is the hope not only for Bolivia but for all the people on the planet," says Morales, who, according to polls, was probably elected to a second term in elections yesterday.

If Morales gets his way, he will upset a market now controlled by two publicly traded companies: Princeton, New Jersey-based Rockwood Holdings Inc., which is 29 percent owned by Henry Kravis's KKR & Co., and Santiago-based Sociedad Quimica y Minera de Chile SA, or Soquimich.

These two companies produce about 70 percent of the world's low-cost lithium from a salt flat in Chile, just across the Andes from Bolivia.

Investors are wooing President Morales to be partners in building a Bolivian mine. French billionaire Vincent Bollore, South Korea's LG Corp. and Japan's Mitsubishi Corp. and Sumitomo Corp. offered to join with Morales in the project. They're already helping the government at no cost to design the mine.

So far, Morales has rebuffed outside investment, saying he wants to keep lithium in government hands to provide local Indians with jobs. Morales says he may change his mind if Bolivia can't raise the $800 million it would cost for construction of a mine and processing plants.

‘Like Saudi Arabia'

"If the Bolivian state had the money, it would invest it," he says. "If the state doesn't have cash, then we're going to look for investment."

Quisbert, the orphaned son of a llama herder, helped persuade Morales in 2007 to pledge $6 million to start work on what could be the largest lithium mine in the world by 2014, says Saul Villegas, who oversees lithium reserves at state-owned mining company Corporacion Minera de Bolivia. Bolivia has 35 percent of the world's lithium resources, according to the USGS.

"Bolivia could become like Saudi Arabia," says Gabriel Torres, an economist for Moody's Investors Service Inc. in New York. "It has a huge amount of the world's reserves."

Carmakers are betting that electric vehicles built to run on lithium batteries will help the industry recover from its worst crisis in three decades. U.S. President Barack Obama's administration is providing $11 billion in loans and grants to car and battery makers to reduce the country's dependence on foreign oil.

42 New Models

The world's auto companies plan 42 new electric models by 2012, according to an October study by PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. Instead of running on gasoline, these vehicles will be powered by lithium batteries that are charged with electricity made in plants fueled by coal, natural gas, nuclear power, solar power and wind.

General Motors Co. says electric cars are critical for the once-mighty carmaker to restore its technical edge after it filed for bankruptcy in 2009. Electric models, such as the Volt, will help GM meet U.S. standards requiring automakers to increase the average mileage of their fleets as much as 40 percent by 2020.

"The Volt remains our top priority as far as advanced technology goes," GM Vice Chairman Bob Lutz says. The company expects the Volt to get the equivalent of 230 miles (370 kilometers) per gallon (3.8 liters) of gasoline.

Treating Depression

By 2020, one in 10 cars manufactured -- or more than 6 million vehicles -- may be powered by lithium batteries, says Carlos Ghosn, chief executive officer of Nissan Motor Co. Car battery sales could jump to $103 billion a year in the next two decades, up from $100 million a year as of October 2009, according to a report by Credit Suisse Group AG. Ventures backed by A123 Systems Inc., Dow Chemical Co. and Johnson Controls Inc. are planning to ramp up production of lithium car batteries or cells.

About 75 percent of commercial lithium is still used for other things: It helps make glass and ceramics heat resistant, it's a lubricant and it's used in a drug to treat depression.

No other metal is better at holding a charge and dissipating heat with as little weight, making lithium the best ingredient known to make batteries for electric cars. Such batteries use a derivative called lithium carbonate to hold electricity they get when plugged into an outlet to be charged.

"Lithium is a very important commodity for the battery," Ghosn says. "Obviously, we're going to need to import a lot of it. Countries that have reserves of lithium are going to benefit."

‘Could be a Rush'

Companies such as Apple Inc., Hewlett-Packard Co. and Nokia Oyj started using rechargeable lithium ion batteries a decade ago, and today they are in millions of iPods, computers and mobile phones.

"There could be a rush to grab up supplies of lithium," says Alex Molinaroli, president of Johnson Controls Power Solutions, part of the world's biggest car battery maker. "You'll see different folks positioning themselves to secure rights to lithium in the future."

Still, electric cars are a gamble. No one knows how many consumers will buy them, and they're a long way from performing like gasoline-powered vehicles. GM's Volt, planned for production in 2010, can go only 40 miles before its battery is drained. Then, a gasoline-powered generator kicks in. An owner can recharge the battery by plugging it into an electrical outlet at home.

Starting the Mine

Bolivia's desolate salt flats are at the center of a global rush for lithium. Villegas, the state mining company executive, says a processing plant will start making lithium carbonate in 2010.

By 2014, the mine will produce 30,000 metric tons of lithium carbonate, more than Rockwood's mine in Chile, which is the world's second largest. Bolivian scientists say there are about 95 million tons of lithium under the Uyuni Salt Flat, more than 12 times Chile's reserves. Car and battery companies want a piece of the action. Bollore and his friend, French President Nicolas Sarkozy, have met with Morales to discuss lithium. Bollore, who controls a multibillion-dollar banking, media and shipping empire, owns a lithium battery plant in France and plans to build electric cars.

In February 2009, Morales, during a state visit to France, test-drove Bollore's Bluecar. Bollore then told Morales they would fund a $5 million study for a mine and help finance construction of a lithium-processing plant.

‘The 21st and 22nd Century'

"It's you who controls the raw materials for the 21st and 22nd centuries," Bollore told Morales, according to a videotape of the meeting. "You are like Saudi Arabia."

Bolivia is up against big odds, says Eduardo Morales, manager of Rockwood's mine in Chile's Atacama Salt Flat. Bolivia's salt flat has few paved roads, and most communities don't have electricity. The country is landlocked; the nearest port is across the Andes, hundreds of miles away in Chile. And Bolivia has no experience mining lithium.

"They will need outside investors," says Morales, a Chilean national unrelated to Bolivia's president.

Rockwood and Soquimich can sell lithium for about three times what it costs to produce because, until now, production hasn't been able to keep up with demand, says Brian Jaskula, a lithium specialist at the USGS in Reston, Virginia.

Evaporating Pools

On Chile's Atacama Salt Flat in the driest desert on Earth, Rockwood and Soquimich produce lithium from evaporating pools that stretch for miles across a sea of formations made of salt. They create those ponds by pumping out lithium-rich water, and then wait 18 months for most of it to evaporate.

Then, they process the remaining liquid into powdered lithium carbonate. It costs about $1 to produce a pound (454 grams), Rockwood's Morales says. Rockwood and Soquimich sell the powder for about $3 a pound.

"This is a good business, and here's the money, right here," says Eduardo Morales, standing at a 1,000-foot-wide (300-meter-wide) pool filled with lithium-bearing water that looks and feels like olive oil at Rockwood's mine in Chile.

Rockwood and Soquimich have big sway over prices because they have few competitors.

"That's what this market is," Jaskula says. "It's dominated by one or two big players."

Lithium Carbonate Prices Jump

Kravis's KKR created Rockwood in 2000 with the acquisition of U.K.-based Laporte Plc's specialty chemical business, and four years later acquired the lithium mine by purchasing Chemetall Plc. Under CEO Seifi Ghasemi, Rockwood boosted annual revenue fourfold, to $3.4 billion in 2008.

KKR took Rockwood public in 2005 and reduced its 100 percent stake to 29 percent. KKR co-founder Kravis declined to comment.

In 2009, lithium carbonate prices jumped to $6,500 a metric ton, almost tripling 2006 values, because of surging demand for batteries, Jaskula says.

Swedish pharmaceutical researcher Johan August Arfvedson discovered lithium in 1817. It wasn't until 1923 that German steelmaker Metallgesellschaft AG began producing lithium on an industrial scale. Bolivia's government and USGS geologists discovered lithium beneath the Uyuni Salt Flat in 1976.

Quisbert inspired Bolivia to move to the center stage of the market. The orphan took off on his own at the age of 12 to dig minerals by hand from the salt flats of South America's Andes Mountains.

Generating Jobs

By the time he was in his 20s, in the 1960s, Quisbert was organizing farmers to pressure for jobs and better living conditions.

Quisbert says he became convinced that Uyuni's lithium, if mined by the government, would generate jobs and revenue that could bring prosperity to the impoverished Indian families who live in mud huts amid the desolation of the salt flat.

Quisbert envisions lithium bringing power to a place where electricity is a luxury. He grew up around Uyuni, which is one of Bolivia's poorest regions. It's inhabited by subsistence farmers and llama herders who tend small farms with no electricity. Towns around the salt flat have frequent power outages.

"Roads and electricity come with a lithium mine," says Quisbert, whose face is tanned and wrinkled from a life in the intense sun of Uyuni. "We still live with candles, with oil lamps."

Lobbying Government

In the 1980s, Quisbert lobbied the government, unsuccessfully, to construct a mine. In 1991, he organized street protests to successfully block plans by Philadelphia- based FMC Corp. and Soquimich to build a lithium mine in Uyuni. FMC gave up and opened a mine across the border in Argentina.

In 2005, Quisbert's friend, Morales, was elected as the first Indian president of Bolivia. Morales had grown up poor, like Quisbert, in Bolivia's Andes, working on farms since the age of 6.

The two men first met in the 1980s, when Morales led Bolivia's biggest coca farmers union.

As Quisbert pushed for a government-run lithium mine, Morales organized protests that helped to force two presidents from office because they had allowed oil companies to exploit Bolivia's natural gas reserves.

Both men believed that foreigners had looted Bolivia's riches, starting with Spanish conquistadors five centuries before, leaving its Indian majority in poverty.

Presidential Palace

Today, Bolivians have an annual per-capita income of $1,716, according to the International Monetary Fund. Bolivia is the second-poorest nation in South America, after Guyana.

"He was fighting for coca; I was fighting for lithium," Quisbert says.

In November 2007, Quisbert walked into the presidential palace in La Paz, past guards dressed in red uniforms. It was 5 a.m., when the president routinely starts his workday, and Quisbert sat down in the palace's Room of Mirrors to propose that the government mine lithium.

Morales, who calls Quisbert Comrade Lithium, agreed within minutes, saying the project would provide jobs.

"The president was very enthusiastic," says Quisbert, who in turn calls Morales Comrade Coca.

The president chose two of Quisbert's friends and advisers to lead the lithium program. One was Villegas, a tattooed, 34- year-old union leader who'd worked for years with Quisbert, to oversee lithium mining.

Planning the Project

Belgian physicist Guillaume Roelants, who had spent 28 years mining southwest Bolivia and teaching Indians how to farm and mine, was charged with planning the project.

On the Uyuni Salt Flat, engineers fill metal and plastic containers with brine to test how quickly it will evaporate. Workers are building a small plant to test how to process lithium carbonate.

Roelants, the mine planner, is working with car and battery makers who could become investors to solve the challenges of building a lithium mine from scratch.

He set up a committee that includes French mining company Eramet SA; state-owned Japan Oil, Gas & Metals Corp.; South Korea's LG Chem and state-owned mining company Korea Resources Corp.; Brazil's Ministry of Science and Technology; and Bollore. University researchers in Brazil and South Korea, working with the committee, are studying how to process the lithium.

Thierry Marraud, Bollore's chief financial officer, has technicians testing brine samples. Researchers at Paris-based Eramet are seeking ways to separate magnesium impurities from the brine.

‘Huge Potential'

"We are going to try to evaluate the total potential, which is huge," Roelants says.

Bolivia is looking, for the first time in its history, to take over bragging rights from Chile. Quisbert is convinced Bolivia can succeed. He sits in his office in a dusty desert town, backed by a portrait of President Morales and the checkered flag of Bolivia's Indians.

For decades since geologists discovered the Bolivian reserve, political opposition and a lack of funds have gotten in the way of developing it. Quisbert says that will change.

"We want a different Bolivia," he says. "We want development in our country."

Battery and car companies around the world are hungry to tap into Bolivia's massive reserves of lithium. The country is betting that lithium can turn it into a global force in the auto industry.

The odds are stacked against it because of its poverty, politics and lack of know-how. If Bolivia chooses to partner with investors from around the world, it may yet become the Saudi Arabia of lithium.

To contact the reporters on this story: Michael Smith in Santiago at Mssmith@bloomberg.net Or Matthew Craze in Santiago at mcraze@bloomberg.net.