Peruvian soldiers at one of their bases in VIscatan. The Peruvian army has set up five bases in the Shining Path's stronghold

Peru guerrillas tread a new path

February 1, 2009 - BBCNews

By Dan Collyns, BBC News, Ayacucho

For most Peruvians, the Shining Path is now just a bad memory.

Memories of bloody massacres and terror in the Andes, bomb attacks and blackouts in the capital Lima, and the hammer and sickle graffiti daubed in red on buildings across the country.

But for a few, the guerrilla group - one of Latin America's most notorious - is still a reality.

Recently the Shining Path has sprung back from relative obscurity to launch its most deadly attacks in more than a decade.

Over the past year, rebels have killed some 25 soldiers and police officers in ambushes and gun battles.

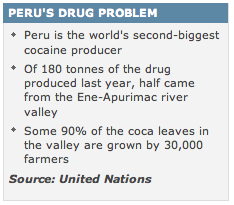

The Shining Path today is a fraction of its former size and is split between two cocaine-producing zones of Peru, some 500km (311 miles) apart.

It is made up of a few hundred guerrillas who did not lay down their arms when the group's leader, Abimael Guzman, declared the armed revolution at an end after his capture in 1992.

Expert in guerrilla warfare from years of resistance in some of Peru's remotest and wildest country, and well-armed from the profits of the cocaine trade, the Shining Path - or Sendero Luminoso in Spanish - is forcing the Peruvian army to fight new battles in an old war.

Hunting the guerrillas

Operacion Excelencia 777 is the codename used by Peru's armed forces for its co-ordinated offensive against the most recalcitrant guerrillas. They are based in and around the Ene-Apurimac River Valley - an area which straddles the Andes mountains and the Amazon jungle - known as the VRAE.

The guerrilla stronghold has to be seen from the air to understand the scale of the task the armed forces face. From a military helicopter, we could see how knife-like peaks covered in dense tropical forest drop into sinuous canyons.

It is some 300 sq km of no-man's land, spanning the entire northern tip of Ayacucho province. By dominating this area, the guerrillas controlled a key drug-trafficking corridor, as well as a conduit for illegal logging.

We flew towards a bald spot on the side of a steep hill, which on closer view revealed itself as a military camp.

The commanding officer ordered us to stay low and seek cover as we jumped out of the helicopter with the commandoes.

Guns pointing in every direction, they took position against possible sniper fire while a second armed helicopter hovered nearby.

This is Viscatan, the river which gives the whole area its name, the heart of Shining Path territory. A few dozen special forces soldiers live in a network of trenches on this exposed hillside.

Ali, as the officer is nicknamed, says battles have been fought here as they try to hunt down the guerrillas on their own terrain.

'Narco-terror' ultimatum

Since the end of August the armed forces have established five bases in Viscatan - the largest is home to more than 100 soldiers.

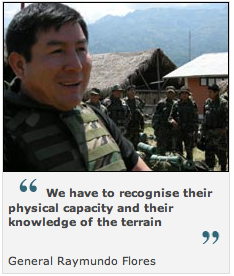

Tenacity, bravery and patience is their motto and they will need all of these qualities, particularly the last one, says the man in command, General Raymundo Flores.

"Sendero haven't taken any big hits", he says.

"It's a question of patience, little by little we are eliminating them.

"We have to recognise their physical capacity and their knowledge of the terrain."

He estimates they have killed around 20 guerrillas, but probably none of the leaders.

Such is the terrain, they have had to try to calculate the number of enemy dead from the vultures circling overhead, Gen Flores says.

Four soldiers have been killed in this operation so far, and around 30 injured, mostly by home-made landmines laid by the guerrillas.

Nonetheless Gen Flores is confident the rebels can be beaten within five years.

"The state has made the decision to finish with narco-terrorism", he says.

"There may not be big steps so far, but the decision to do so is a big advance."

New tactics

As far as Gen Flores is concerned, it is not the same Maoist group which practically toppled the state in the early 1990s.

It is a breakaway group led by three brothers Jorge, Victor and Carlos Quispe Palomino, whom he accuses of being a drug-trafficking clan.

(right) Peruvian soldiers: Soldiers have to drop quickly into the region

(right) Peruvian soldiers: Soldiers have to drop quickly into the region

"The ideology is a pretext, they are just narco-terrorists," Gen Flores says, echoing the statements made on the leaflets they drop from the air into villages in the zone. "They're only in it for the money."

However, leaders from the valley's self-defence committees, the civil militia which fought a bitter war with the Shining Path in the 1980s and 1990s, say the Shining Path guerrillas continue to recruit and expand while maintaining their revolutionary ideology.

Peru's Truth and Reconciliation commission estimated more than 69,000 people died in fighting between the rebels and the military between 1980 and 2000; more than half of those at the hands of the Shining Path.

"Before the Shining Path used to enter the community and kill people; men, women and children," says Frolyan Gutierrez, a village leader in the poor community of Sanabamba.

"They stole all our livestock, and left us with nothing.

"We begged for an army base to be established. But later, the guerrillas reappeared and they were different; they bought things with their money, instead of just taking them, and invited us to play football."

One step ahead

Drug-trafficking has helped the Shining Path to regain its strength.

(right) Children in Sanabamba. Soldiers give out clothes in a bid to win the villagers' support

(right) Children in Sanabamba. Soldiers give out clothes in a bid to win the villagers' support

But it continues to have "political and military aims", says Gustavo Gorriti, a journalist and author on the guerrilla group.

"I don't think this chapter with the Viscatan offensive ends this story, not by any means", he says.

"They haven't suffered, at this point, so far as it is known, any significant losses, they have lost territory but for a guerrilla organisation that is a thing they are used to."

The Shining Path is a long way from becoming the national threat it was during President Alan Garcia's first term between 1985 to 1990.

But so far the Shining Path has shown it can still stay one step ahead of the state.