Fujimori's mega-trial draws to a close

For the past 15 months Peruvians have been able to tune in live to the trial of their former leader on television.

April 4, 2009 - BBC News

By Dan Collyns - BBC News, Lima

(right) Fujimori supporters, undated picture. The 15-month trial of Alberto Fujimori has divided the nation.

(right) Fujimori supporters, undated picture. The 15-month trial of Alberto Fujimori has divided the nation.

At times riveting but often tedious and procedural, what has been called "the mega-trial" is the longest, most complex and costliest in Peruvian history.

To some it is shameful and wrong that Alberto Fujimori - the man they credit with putting the economy back on track and defeating the brutal Mao-inspired insurgency of the Shining Path - should now be on trial.

But almost three-quarters of the population, according to opinion polls, believe he will be found guilty of charges he was responsible for two death squad killings and two kidnappings - as well as those of corruption, embezzlement and phone-tapping which will be heard in two more trials which will begin in May.

Inside coup

Mr Fujimori is the first democratically-elected leader in Latin America to be tried in his own country for human rights abuses.

The trial has been praised for meticulous attention to judicial procedure, fairness and impartiality.

"Peru is making history by conducting a domestic trial of a former head of state who stands accused of grave violations of human rights," said Jo-Marie Burt, a Latin American Studies professor at George Mason University and an international observer at the trial.

"It is a major accomplishment, and the international community is taking notice."

There was a strong show of support for the 70-year-old at the end of his trial, as he shook off his hitherto downtrodden appearance to testify in his own defence.

Hundreds of his supporters came in from the outer suburbs of Lima, dressed in the orange colours of his party, to show their allegiance.

As well as attempting to refute the allegations against him, Mr Fujimori made a defiant political address summoning up his populist rhetoric and describing himself as the man who pulled Peru from the bottom of the abyss and defeated the twin evils of hyperinflation and terrorism.

"I had to govern from hell, not from the government palace, the hell that terrorism had installed in three quarters of Peru," he said.

"I only hope that those who sentence me try to imagine that hell and don't try to civilise it from a distance."

He admitted while his "pacification strategy" had been largely "clean and successful", there had been "regrettable isolated incidences".

But he said history and the Peruvian people would judge him as the man who brought peace, a clear sign, said prosecutor Carlos Rivera, that he knows he will be found guilty and "ridiculous because this impeccably conducted trial is the real justice".

During his time in power, many Peruvians believed in his "desperate times call for desperate measures" justification. He had strong backing, even when he used soldiers and tanks to dissolve congress and the courts in an overnight operation in April 1992, a move which became known as the auto-golpe - or inside coup.

'Dirty war' deaths

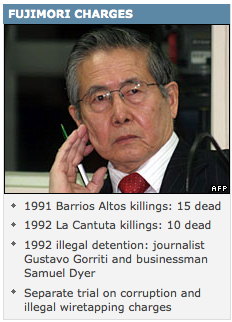

It was in those early years that the Barrios Altos and La Cantuta massacres took place. In a time when mass killings and atrocities were commonplace, these two drew particular attention.

In 1991, 15 people, including an eight-year-old boy, were killed when soldiers from a special army intelligence unit raided a barbecue in Barrios Altos, an inner-city neighbourhood in Lima.

(left) Keiko Fujimori at a rally calling for her father's release, Lima, Peru, 25 March 2009. Keiko Fujimori has said she would not hesitate to pardon her father if elected.

(left) Keiko Fujimori at a rally calling for her father's release, Lima, Peru, 25 March 2009. Keiko Fujimori has said she would not hesitate to pardon her father if elected.

And in 1992, nine students were dragged from their dormitory beds in La Cantuta University, by the same La Colina death squad.

Along with a professor, they were killed and their charred remains were later found on a patch of waste ground on the outskirts of Lima.

Gisela Ortiz, the sister of one of those students, blames Mr Fujimori for the death of her brother, Enrique, because, she says, he created La Colina and was the architect of the "dirty war", allegations the former leader has consistently denied.

Mr Fujimori is also accused of orchestrating the abductions of a businessman, Samuel Dyer, and a journalist, Gustavo Gorriti after the 1992 coup.

These four cases make up the human rights case against the former leader.

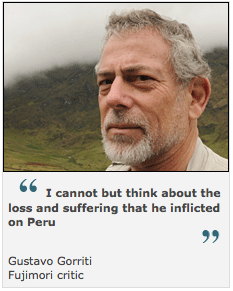

Gustavo Gorriti, an outspoken critic of Mr Fujimori who was forced to leave Peru along with his family during most of the 1990s, says he does not feel "any personal satisfaction" from the fact that Mr Fujimori will go to jail.

"But at the same time I cannot but think about the loss and suffering that he inflicted on Peru," he adds.

"I think that justice has to deal with that."

Boost support

While justice may be blind on this occasion, the ramifications of a guilty verdict for Mr Fujimori could send shockwaves through political circles in modern-day Peru.

(right) Carlos Raffo believes a guilty verdict will boost Fujimori's support

(right) Carlos Raffo believes a guilty verdict will boost Fujimori's support

Carlos Raffo, one of the 13 Fujimori supporters in Peru's 120-member congress, believes that if he is found guilty, it will boost his support and propel his daughter Keiko into office in 2011.

Keiko, Mr Fujimori's political successor, has has not formally announced her candidature for the 2011 elections. But the 33-year-old was the front-runner in a recent Lima-based opinion poll.

She has said she would not hesitate to pardon her father if she became Peru's president.

Peru's governing APRA party of President Alan Garcia has both a tacit and explicit relationship with the Fujimoristas.

Among other things it relies on them to help pass legislation in Congress.

Mr Garcia's first presidency immediately preceded Mr Fujimori's and his mandate saw gross human rights violations committed in the fight against the Shining Path.

Went too far?

A government-appointed truth and reconciliation commission which investigated Peru's 1980-2000 civil conflict held Mr Garcia politically responsible for military abuses.

Mr Fujimori asked pertinently in his final address why he was the only one being tried for massacres committed during his leadership.

Whether President Garcia pardons Mr Fujimori will depend of the severity of the sentence, the state of public opinion and his personal health, says Gustavo Gorriti.

"I think there is a modestly high probability that he will," he says.

Democracy and respect for human rights may have been low on the list of priorities for many Peruvians in the dark days of the 1990s.

El Chino's populist mix of public works and authoritarianism continues to have its followers.

"He's the best president this country's ever had," says Miguel Torres, a taxi driver in Lima.

"We now live in a peaceful country, with economic growth and without terrorism or violence thanks to Fujimori."

"People have mixed feelings for him", says psychoanalyst Jorge Bruce.

"On the one side I think they recognise what he did and they are grateful to him, but at the same time there is such huge evidence of his crimes that I think many people feel uncomfortable.

"He just went too far."