Slide Show (8 photos) Go to Original Story.

Cocaine trade revitalizes Peruvian rebels

May 10, 2009 - Associated Press

By ANDREW WHALEN

UNION MANTARO, Peru -- The last town on a rutted dirt road in Peru's most prolific cocaine-producing highland valley, Union Mantaro has no police post, no church and no health clinic. Its 600 people lack running water and electricity.

Until January, makeshift huts of wood and plastic housed scores of refugees from a government offensive against a small but lethal band of drug-funded rebels, revitalized remnants of the fanatical Shining Path guerrilla movement.

Most have since returned to outlying mountain villages as the rebels frustrated the army's campaign against them, killing 33 soldiers and wounding 48 since the military arrived in August. The rebel death toll is unknown.

The army's setbacks _ the narcotics trade does not appear to have been dented _ are more than a worrisome embarrassment for the central government in faraway Lima. Critics say President Alan Garcia needs to act fast or risk greater instability.

Peru's cocaine trade _ No. 2 after Colombia's _ is booming after a 1990s drop-off. The government calls the insurgents who've used it to rearm ideologically bankrupt, but peasants who have coexisted with them don't necessarily agree. At least not publicly.

The gateway to the Shining Path's jungle-draped stronghold, Union Mantaro is a bumpy two-day drive down the Andes' eastern slopes from the provincial capital of Ayacucho, where the movement was born nearly three decades ago.

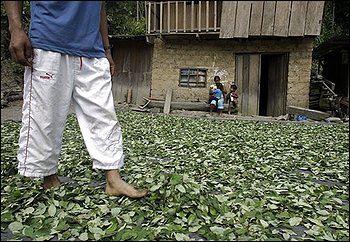

Along the road into the Apurimac and Ene valley, women and children dry coca leaves on long canvas beds in front of half-built, brick homes. A pro-coca political party has painted the leaf on wooden shacks in villages so poor that parents must chip in to pay teachers' salaries.

Coca production soared in this rugged region just 100 miles from the world-renowned Machu Picchu ruins as migrants more than doubled its population to some 240,000 in little more than a decade.

Growing the crop, a mild stimulant widely chewed in the Andes, is legal in Peru, but authorities say nine-tenths of it goes to the illegal manufacture of cocaine.

"Politicians in Lima don't know what's going on in these communities. If they did, they would know the solution to the problem isn't more soldiers," says Marisela Quispe, a government worker who keeps track of victims of political violence.

Experts say the rebel group _ Sendero Luminoso in Spanish _ now has some 400 well-armed fighters in two separate groups. The larger contingent moves with ease in the lush mountains flanking this valley.

It has spies in every village, allies forged through the drug trade who immediately send word when soldiers head out on patrol, says army Maj. Chirinos Carlos Rivera. His 150 soldiers are based downriver from Union Mantaro.

The locals, says Quispe, see no alternative to drug trade.

Behind the trappings of a narco-economy _ 4x4 pickups and well-stocked agrochemical stores _ the valley is poor. More than half the people live on less than $2 a day.

Union Mantaro has long been a drug trade hub. Before the army arrived, guerrillas shouldering AK-47s and Galil assault rifles routinely filed into town to buy supplies, and attracted migrants by offering free land to coca growers.

"They gave you a hand in clearing the jungle, handed out supplies and food, maybe a hatchet. All to help you start out," says Abran Rojas, 27, a coca farmer who arrived in 2006.

He settled in Pampa Aurora, a village of 60 people a six-hour walk above Union Mantaro along a prime smuggling route. He said 10 to 20 smugglers would file past carrying cocaine-filled backpacks a few times a week, accompanied by rebels clad in crisp, dark-blue or green uniforms.

Then came the army offensive.

Soldiers shot and killed four people in one village in September, says Norberto Lanilla, a lawyer representing the victims' relatives.

"They called us terrorists and collaborators. After the killings we had a week to grab what we could and leave," Rojas said of the soldiers.

Defense Minister Antero Florez defended the soldiers, saying anyone living in the rebel-dominated mountains should be considered an insurgent.

Rojas and other refugees deny they are collaborators. But they say it's best to avoid contact with the military.

"The soldiers try to use you quickly, for information, as guides. But if you guide, 'Los Tios' don't forgive. They kill," Rojas says. The rebels are known as "Los Tios," Spanish for the uncles.

The government says the repackaged Shining Path differs little from the far larger leftist Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia in the neighboring Andean nation. It says they are simply militarized drug gangs.

Rojas and other refugees from Pampa Aurora aren't so sure. They say the Shining Path fighters appear to have a political agenda and sit peasants down every few weeks for lectures.

"They tell you the government has forgotten the poor. That our rights are stomped on by the rich, the police, the military," he said.

It took some persuading, though, to get 33-year-old Obertino Coro to return to Pampa Aurora four years ago, he said.

In 1984, he fled the village after watching guerrillas hack his father, an ex-soldier, and two other men to pieces, then burn the village to the ground. The three men had joined a militia formed to fight Sendero.

Coro returned after running into rebels in the jungle who told him they now reject using violence against civilians.

Which does not mean the new Sendero tolerates military collaborators. It recently hauled away a member of a pro-government militia when it turned back a group of peasants trying to return to Pampa Aurora.

He has not been heard from since.

"They're wolves in sheep's clothes," says Wagner Tineo, chief coordinator of the region's militias, which he said have waned due to government inattention.

Not since the 1990s, under then-President Alberto Fujimori, has the government provided the militias with weapons.

Fujimori, whose presidency ended in scandal, was convicted last month and sentenced to 25 years in prison for killings and other military abuses committed during his decade in power. Nearly 70,000 people were killed from 1980-2000 as security forces and Sendero rebels routinely killed those suspected of collaborating with the enemy side.

The movement faded after the 1992 capture of Sendero founder Abimael Guzman, but in recent years remnants evolved into a cocaine-processing and smuggling mafia.

The Apurimac and Ene valley produces more than a third of Peru's coca crop, which the United Nations estimated at 53,700 hectares for 2007 _ the highest in a decade.

The United States gave Peru $61.3 million in anti-drug aid last year _ though the manual eradication and crop substitution it funds are farther north in the Upper Huallaga valley, where police have had success against the smaller Shining Path band.

Gen. Alcardo Moncada Novoa, the army commander for the Apurimac and Ene region, says his troops have it tough by contrast: The rebels "know the terrain and have been in the area for 20 years."

On April 9, rebels killed 15 soldiers in an ambush, some blown sideways off a mountain by dynamite. The rebels didn't spare their wounded commander.

"The captain was still alive and they finished him off with machete blows and rocks. They destroyed his skull," the newsmagazine Caretas quoted survivor Sgt. Jose Huaman Silva as saying.

The military alone can't defeat the insurgents, say officials in the region. They say the bureaucracy that has hindered development must be surmounted.

A project due to finally bring electricity all the way to Union Mantaro was launched in 2003. And the government has promised to improve the road _ and even extend it to Pampa Aurora.

A paved road promised since the 1990s, on which public bidding has yet to begin, would finally let residents deliver cacao, coffee and jungle fruits to market in Ayacucho.

But even with the road, simple economics favors the cocaine trade. Currently, coca is harvested four times a year in the valley and sells for $3.30 per kilo while coffee and cacao yield one crop a year and $1.25 to $1.50 a kilo.

Gen. Moncada says battling Sendero and destroying drug labs aren't enough.

"Controlling the trade in cocaine's chemical precursors would be the first true advance against drug trafficking in the region," he said.

At a narcotics police checkpoint in Machente, a village on the main road into the valley, a captain showed Associated Press journalists a register of materials used in cocaine production that have passed into the conflict zone.

In the first week of April alone, 18,000 kilograms of calcium hydroxide, a compound also called slaked lime with various legitimate uses, and 12,000 gallons of kerosene transited the post.

People here say kerosene is not used in homes in the valley, and on April 30, President Alan Garcia decreed a national ban on its sale, calling it a key step in undercutting cocaine production.

It will be a minimum of three months before the ban takes effect.

© 2009 The Associated Press