Morales tries to take revolution to kindergarten

December 9, 2011 - Miami Herald

School reform could be the toughest challenge yet for President Evo Morales, part of an ambitious attempt to remake his Andean nation.

By Emily Alpert -- Special to The Miam Herald

LA PAZ -- Decades ago, when Alejandra Cruz first came to La Paz from the little village of Choquenaira, the other children pulled her long braids, tripped her after class and knocked her bowl of oatmeal onto her shirt.

Aymarista, they called her, making her mother tongue into a slur. The shame stuck. Years later, Alejandra decided against speaking Aymara to her children, fearing they would suffer the same slights.

Today, she teaches preteens in a comfortable zone of La Paz how to count and name colors in the language she once abandoned. She credits Evo Morales, the country's first indigenous president.

"I thank God for this government," she said one day after class.

Bolivia has undergone a sea change under Morales. Six years into his presidency, he has nationalized gas, loosened the rules on coca cultivation and ejected the U.S. ambassador.

Now, he is taking on the schools. Under a new law passed in December, schoolchildren must learn Aymara, Quechua or another local language along with Spanish and a foreign tongue. Schools will teach students to value their cultures, making schools both "intercultural" and "intracultural." The curricula will be tailored to specific communities and students will learn useful trades.

Morales has declared the changes will be a reality within three years. The Ministry of Education is still hammering out new regulations to make schools "decolonizing, liberating, revolutionary (and) anti-imperialist." It is a radical change meant to wipe out centuries of oppression.

The reforms come at a crisis point for Morales. He lobbied hard for a highway that would divide a pristine forest — and divided the indigenous people who once adored him. Street protests exploded last year over soaring prices for gas. And many voters snubbed the elections for judges that he championed.

Remaking the schools could be his toughest battle yet. Bolivia could be called ground zero for the achievement gap, saddled with some of the starkest poverty and most stunning inequality in the Americas. It has a thin budget and a tortuous bureaucracy. Old prejudices are still kicking — and some critics say the reforms will breed new ones by putting Indian cultures first.

"I think it's vengeful," said Gonzalo Rojas, a professor at the Universidad Mayor de San Andres. "Reverse discrimination is not desirable either."

The Ministry of Education did not respond to questions. Last year, Morales told the Bolivian press, "If someone rejects this project, under whatever pretext, that means they still have a racist mentality."

**

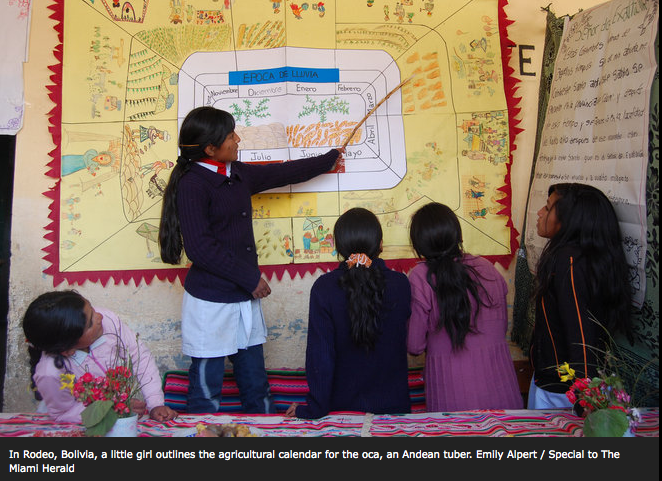

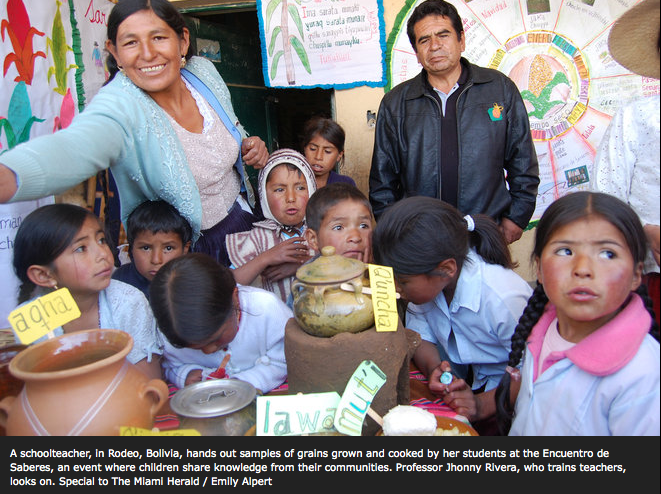

The revolution looks a lot like a science fair. On a sunny day in Rodeo, a farming town in the mountains two hours from Cochabamba, children in little booths papered with posters earnestly explained how to harvest ch'aki jawas beans and earned praise for chanting in Quechua. Teachers-in-training took notes.

"In January the altramuz is mature," a timid boy said in Spanish, explaining the calendar for the Andean legume. "We have to protect it from the birds so they don't eat it. Then in April we sell it to the markets."

"Now in Quechua," fifth grade teacher Romuelda Monasterios urged him. The boy complied.

The old idea that children should shake off their country ways is being turned upside down. Though the government is still installing the reforms, some nonprofits have already been at work in the countryside to remake education, giving a sneak peek at what education reform here might mean.

For instance, "when we teach about medicine from the Western world, we might also ask, 'What are the herbs that your parents and grandparents use to prevent illness?'" said Silvana Gonzales, who handles communications for Faith and Happiness, a Christian non-profit that helped with th event.

Planting potatoes might seem little like school reform. But just like teaching Quechua, the idea is that the schools should teach things that matter to the community. It sounds a lot like the frequent calls for "relevance" in high school reform in the United States -- and potatoes are relevant in Tiraque.

In the remote village of Piriquina in northern Potosi, teenagers tended to the onions they planted earlier this year in the school garden. They've tested the kinds of minerals in the soil to improve their production, learning chemistry outside the classroom.

"We've had high school graduates that know a differential equation perfectly," said Arturo Choque, public policy coordinator for the Bolivian Center for Educational Research and Action, which spurred some of the changes in Piriquina. "But they don't know how they're going to apply it to their lives."

**

The government must win the hearts and minds of more than 160,000 teachers before these ideas can be more than an experiment. It is a tougher sell in the cities, especially with some of the radical teachers unions. A bold poster on the stairwell of the La Paz union decries the reforms as "another lousy law."

"The law is doomed to fail," said Jose Luis Alvarez, the group's president. He argued that, like the last reforms, it merely papered over real economic inequalities. "The only thing that has changed are the names."

The last round of education reform was more than a decade and a half ago, under now-exiled President Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada. It tried to free schools from rigid drills and memorization. It also brought Aymara and Quechua into many schools for the first time.

But teachers resisted, saying the reforms were imposed from the top. Aymara and Quechua barely touched the cities: A World Bank study found less than 1 percent of urban schools ultimately became bilingual. Many rural parents also revolted at the idea of teaching their mother tongues in school.

"We are colonized in our minds," lamented Susana Bejarano, former chief of the education cabinet. Because their languages were so stigmatized, "the parents preferred, logically, to protect their children."

There are important differences between this law and the last one. All schools are supposed to teach local languages, not just schools where kids speak them at home. The old reforms talked about knowing other cultures, while the new reforms talk about knowing your own culture. "Decolonization" is new.

But teachers fret there has been little training to explain the new law. They know they need to learn an indigenous language. "Otherwise we are doomed!" Ramiro Alcazar joked before his Aymara class.

Other ideas are still murky. A new curriculum was supposed to be polished off this summer. That didn't happen. Urbanites are confused about how "productive education" will work in the city. And nobody is sure how to measure whether they're instilling "interculturality."

"If we don't have more detailed regulations," said Luis Cameo Borda, principal of the Rotary Chuquiago Marka high school in sprawling El Alto, "we'll just continue the same way."

Emily Alpert writes about education in Southern California. She reported this story with a grant from the International Reporting Project.