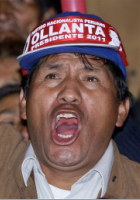

(left & above) Peru's presidential candidate Ollanta Humala, center, of the political party Gana Peru, is carried on shoulders during a campaign rally in Arequipa, Peru, Tuesday, May 31, 2011. Humala, will face Keiko Fujimori, daughter of Peru's former President Alberto Fujimori, in a presidential runoff election on June 5. Photos: Karel Navarro / AP Photo

Leftist Peru candidate dogged by doubts

June 1, 2011 - Miami Herald

By CARLA SALAZAR, Associated Press

LIMA, Peru -- Leftist military man Ollanta Humala has tried hard to shed his radical image and disavow Hugo Chavez, promising not to follow the Venezuelan leader's example of promoting constitutional rewrites that have helped extend his rule.

He's sworn, hand on Bible, his commitment to democracy.

Many Peruvians are dubious. Humala's main rival in Sunday's presidential run-off election isn't so much Keiko Fujimori as voter distrust.

A recent poll by the Datum firm found 49 percent believe Humala poses the greater risk of closing Congress and becoming a dictator - against 21 percent for Fujimori.

The reasons: Humala's past chumminess with Chavez, nagging questions about alleged human rights abuses in his military past and doubts over his sincerity after he repeatedly rewrote his campaign platform to make it more palatable to investors.

"It's very difficult to believe that a person who for years and decades thought and acted against democracy and human rights is suddenly going to change," said Fernando Rospigliosi, a former interior minister. "His track record show he's no democrat."

Then openly aligned with Chavez, Humala narrowly lost the 2006 presidential election to Alan Garcia.

Opinion polls now show him in a dead heat with Fujimori, who many consider little more than a stand-in for her imprisoned father, Alberto. He is serving a 25-year sentence for authorizing death squads and corruption during his 1990-2000 presidency.

"I ask you to give me the opportunity to change things. There may be doubts about me, but there's proof about the other side," Humala, 48, told voters Sunday in a televised debate between the candidates.

Many Peruvians believe a Fujimori victory would restore a dangerously autocratic, kleptocratic regime. But they also well remember that Humala advocated in 2006 the redistribution of the billions earned from mining, which accounts for more than 60 percent of Peru's export income.

Every time a poll has given Humala an apparent edge, Peru's stock market plunges and the U.S. dollar gains against the nuevo sol.

Humala now says the Chavez model "isn't applicable in Peru," that he would manage it as Brazil's Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva did in a business-friendly presidency that balanced poverty reduction with building a middle class.

After winning 32 percent support in the first round of presidential voting on April 10, Humala continually revised his platform. Gone were calls for renegotiating free trade pacts and rewriting the constitution to create "an economic regime with social justice as its objective."

He still insists, however, on taxing windfall mining profits to benefit the poor who account for one in three Peruvians.

Most of Peru's news media is against him, but Humala has succeeded in enlisting center-left academics as advisers and winning endorsements from Nobel literature laureate Mario Vargas Llosa and centrist former President Alejandro Toledo, who finished fourth in the election's first round.

Vargas Llosa, who lost the 1990 presidential election to Alberto Fujimori, even appeared in a Humala campaign ad, exhorting Peruvians to "avoid the mockery of a new dictatorship," a reference to Keiko Fujimori, whose closest advisers also served her father.

Five years ago, Vargas Llosa said a Humala victory would be "a disgrace" and called the cashiered army lieutenant colonel a Chavez disciple.

Venezuelan opposition leader Diego Arria, whose ranch was expropriated by Chavez's government last year, thinks Humala's behavior is similar to Chavez's before his 1998 election.

"Both are coup leaders who were twice frustrated in coup attempts and present themselves, legally and very conciliatory, as lambs," he said.

Humala mounted a short, bloodless coup attempt in 2000 when Alberto Fujimori's government was in the final throes of the corruption scandal that doomed it.

Five years later, in a radio address from Korea where he was military attache, he encouraged his brother Antauro's attempt to trigger an uprising against Toledo. Four police officers were killed, and Antauro Humala is prison serving a 25-year term.

Doubts also linger about Humala's backing by Chavez.

Prosecutors investigated Humala's wife Nadine Heredia in 2009 for allegedly receiving $4,000 a month from a pro-Chavez Venezuelan newspaper, The English-language Daily Journal, without writing a single article for it. That case was closed because Venezuelan authorities never cooperated, prosecutor Eduardo Castaneda told The Associated Press.

And though Humala insists his government would be closer to The United States than Venezuela, many Peruvians believe he would put their nation in the Chavez leftist camp beside Bolivia, Ecuador and Nicaragua.

"It's easier to combat a local dictator, with native roots, than an international project," said Lourdes Flores, a former presidential candidate who heads the conservative Popular Christian party.

Humala is also dogged by allegations of rights abuses from his days commanding a counterinsurgency unit in Peru's Madre Mia jungle during the early 1990s

A 2006 U.S. diplomatic cable obtained by WikiLeaks and published last week by the El Comercio newspaper quotes an unnamed U.S. military officer who befriended Humala in the late 1990s as saying he "talked of having committed some acts of which he was not proud ... of having killed rebels and of some torture techniques used (electric shock, beatings, rapes). (I) don't think he had the stomach for rape, but knew of it happening."

A case that has long hounded Humala also resurfaced in the campaign's home stretch when the affiliated Peru.21 newspaper reported on what it called new information related to a $4,000 bribe allegedly paid to a Madre Mia man to retract an accusation against Humala.

The reported recipient, Jorge Avila, initially alleged in 2006 that Humala was involved in the murder of one of his brothers-in-law and the disappearance of his sister.

The case was dropped, however, when Avila retracted his statement. Peru.21 said Ruben Gomez, a different Avila brother-in-law, helped arrange the bribe.

Humala called Gomez's allegations a fabrication designed to sabotage his candidacy. In brief words with the AP Tuesday after a court appearance, Gomez said he was indeed an intermediary in the bribe's delivery and said the money came from Humala.

It is not clear whether the case will be reopened, but a lawyer with the respected National Human Rights Council, Victor Alvarez, told the AP that after retracting his accusation Avila bought a motorcycle taxi and made improvements to his house.

The council recorded 11 cases of rights violations in Madre Mia in 1992, when then-Capt. Humala commanded the base there, including torture and forced disappearances.

Ironically, the council's director, Rocio Silva-Santisteban, told the AP that while she believes Humala's case should resolved she is more concerned about preventing his opponent's election.

"We're faced by a perverse dilemma," said Silva-Santisteban. "Ollanta Humala makes us suspicious, but we are certain about Keiko Fujimori."

---

Associated Press Writers Frank Bajak and Martin Villena contributed to this report.

---

Carla Salazar on Twitter: http://twitter.com/cardensal

Frank Bajak on Twitter: http://twitter.com/fbajak