Peru's presidential run-off

Victory for the Andean chameleon

June 9, 2011 - Economist

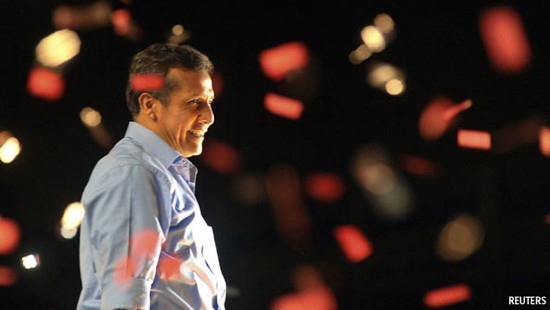

Having reinvented himself as a moderate, Ollanta Humala has an extraordinary opportunity to marry economic growth with social progress

FIVE years ago Ollanta Humala, a former army lieutenant-colonel with no previous political experience, came close to winning Peru's presidency by avowing the statist nationalism practised by Venezuela's Hugo Chávez. On June 5th he achieved his goal, narrowly defeating Keiko Fujimori, the daughter of a populist former president, by 51.5% to 48.5%. To do so Mr Humala eschewed Mr Chávez, modelled himself on Brazil's social-democratic former president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, dropped a leftist government platform he had unveiled only months before and forged last-minute alliances in the centre. Many Peruvians are consequently wondering just which Mr Humala will start governing their country on July 28th.

The uncertainty prompted the Lima stockmarket index to plunge 12.5% on June 6th, its biggest-ever daily fall, though it later recovered most of its losses. Shares in several multinational mining companies with operations in Peru fell sharply too. In victory Mr Humala has tried to strike a reassuring tone while also offering hope to poorer Peruvians who make up his electoral base. "It's not possible to say that the country is progressing when 12m people are living in miserable conditions without electricity or running water," he told cheering supporters. But he also promised "a government of national consensus" that would "promote investment and the free market, which is the consolidation of the internal market".

Mr Humala's transition team, announced this week, mixes leftist academics with centrist former officials from the government of Alejandro Toledo (2001 to 2006), a defeated rival who backed him in the run-off. Pundits called for Mr Humala to put an end to the uncertainty by naming key cabinet appointments quickly. These might include Beatriz Merino, a capable centrist, as prime minister. And Mr Humala is said to want Julio Velarde, who is respected by investors, to stay as Central Bank governor.

Mr Humala's journey to the centre began when he adopted many of Lula's campaign tactics and brought in political advisers from Brazil's ruling Workers' Party. But in the campaign for the first round of the election, on April 10th, he was still proposing a "nationalist" economic policy and pledged to unpick contracts that have brought private investment in mining, gas and infrastructure. Mr Humala topped that poll, but with just 31.7% of the vote. His votes were mainly those of the Peruvians, especially in the southern Andes, who have yet to feel much benefit from an extraordinary economic boom that has seen growth average 5.7% a year over the past decade and poverty fall from 48% in 2005 to 31% in 2010.

Mr Humala's immense good fortune was that the centrist vote was split between three candidates, and so his opponent in the run-off was Ms Fuijimori. As president from 1990 to 2000, her father, Alberto Fujimori, laid the foundations of the economic boom with free-market reforms but ruled as an elected autocrat. He is serving a 25-year sentence for human-rights abuses and corruption. Many Peruvians who abhor Mr Humala's politics could not bring themselves to vote for his opponent. Her defeat means that Mr Fujimori will remain in detention and probably quashes his hopes of founding a dynasty.

Whereas Ms Fujimori surrounded herself with her father's conservative aides, Mr Humala moved closer to the centre. He dropped his original platform and plan to change the constitution. He swore on the Bible to maintain Peru's economic framework. In the end he probably owed victory to the support of Mr Toledo, who won 16% of the vote in April, and of Mario Vargas Llosa, Peru's Nobel laureate for literature.

The main doubt about Mr Humala is that he is not Lula. Brazil's former leader is a politically astute and pragmatic former trade-unionist, who fought a military regime. As an army officer, Mr Humala led one military rebellion and backed another by his brother, who is a fascist. In many ways he embodies the continuing appeal of authoritarianism in Peru. Part of his appeal to poorer voters was that he promised to be harsh on crime and corruption.

The main reason for optimism about his government is that Peru's recent success will constrain his freedom of manoeuvre. Mr Humala's leftist coalition has only 47 of the 130 seats in Congress. Mr Toledo, whose party has 21 seats, is well placed to help--and to put limits on change. It helps, too, that Mr Chávez is a spent force whose main achievement is to have squandered an oil boom. When it comes to models, Brazil trumps Venezuela. In addition, the election showed that there is broad public support for continuity in economic policy.

But it also showed that many Peruvians want the government to do more on social policy. Some of Mr Humala's proposals are sensible enough. He wants to expand a small conditional cash-transfer programme, introduced by Mr Toledo and aimed at helping the poorest Peruvians. He promises to expand child care, and introduce pensions for those who lack them (though unless done carefully this risks undermining efforts to draw more Peruvians out of the vast informal economy). Thanks to the inexplicable neglect of social policy by Alan García, the outgoing president, Mr Humala has the chance to take some easy and popular steps. Trickier will be whether he shows the courage and political intelligence needed to improve the quality of government in Peru, perhaps the country's biggest weakness.

The most controversial issue will be the treatment of mining and natural-gas investment. Mr Humala wants a windfall tax on mining, but says he will talk to the companies first. Much will depend on the details. He seems to have watered down his previous opposition to the export of natural gas. But he backs a law to give a veto--rather than the right to consultation--to Amerindian communities over mining development on their lands.

The new president's new-found moderation applies to foreign affairs as well. Gone is the Chile-bashing of the nationalist caudillo who fanned Peruvians' visceral dislike of the neighbour which twice defeated them in 19th-century wars. The United States is a "strategic partner", he said this week. He is likely to follow Brazil's lead in South America. That means he may drop Mr García's plan for a common market with Chile, Colombia and Mexico.

Since he takes over when Peru's circumstances have rarely been better, Mr Humala has an extraordinary opportunity to be a successful president. It has taken spectacular political incompetence on the part of the centrists who engineered the boom to hand the country over to the candidate whom its business and political establishment dismissed as "anti-system". They can draw some solace from the fact that Mr Humala won by pledging to uphold many of the system's pillars.