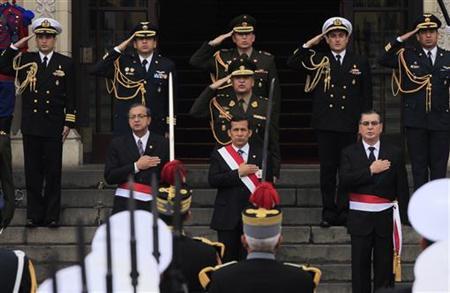

(above) Peru's President Ollanta Humala (C), accompanied by Defense Minister Daniel Mora (L) and Interior Minister Oscar Valdes, attends a ceremony that recognizes him as supreme chief of the Peruvian Armed Forces and the National Police institution, at the government palace in Lima, August 3, 2011. Photo Credit: Reuters/Pilar Olivares

Peru's Humala unveils new governing style: silence

August 11, 2011 - Reuters

By Marco Aquino

LIMA (Reuters) - Two weeks into his five-year term, Peru's President Ollanta Humala has retreated from the public spotlight, showing an odd reluctance to discuss policies, scandals or even his plans for running the country.

Unlike his irrepressible predecessor, Alan Garcia, who took to the airwaves nearly every morning at dawn to opine about everything from rural poverty to French philosophy, Humala has been all but silent.

Most Peruvians disliked Garcia for a style derided as long on theatrics and lofty rhetoric -- he once held a ribbon cutting ceremony for a hospital that hadn't been built -- and short on hard-nosed, hands-on governing. Comics used to say he suffered from verbal-rrhea.

Humala, 49, may be going too far the other way.

A career military officer holding an elected post for the first time, he has said almost nothing in public since his July 28 inauguration speech, snubbing local media that his camp accused of biased coverage during a bruising election campaign.

His cabinet chief, Salomon Lerner, even issued a directive last week forbidding Humala's ministers, who span the ideological spectrum from left to right, from talking publicly about "big picture philosophical questions."

Critics say the silence is more than just a case of getting accustomed to a new role and setting up his cabinet.

"Humala doesn't dominate language so there is a risk he could put his foot in his mouth," said Fernando Rospigliosi, a former interior minister and a newspaper columnist. "He's overwhelmed by questions and has a team that is too heterogeneous to reconcile everybody."

Humala has appointed some centrists and even a conservative to his cabinet, irking hardliners in his left-wing party miffed that he has begun to court foreign investors he once railed against in one of the world's fastest-growing economies.

Staying above the fray allows him to avoid taking firm stances on controversial issues that could anger his base, unnerve investors or hurt his approval rating, now around 40 percent after peaking at 70 percent following his June 5 election victory.

Pushing back against criticism from one legislator who complained the cabinet was "muzzled," Lerner said on Wednesday the ministers have total freedom to talk about their own portfolios and said Humala has been too busy since taking office to speak in public.

"People have different styles, and he is taking care of other responsibilities," Lerner told reporters. "He has asked the cabinet to communicate with the press -- something he will do at the right time."

But the strategy of silence has also hurt Humala.

CONSTITUTIONAL ROW, BROTHERS

It took days for his Gana Peru party to respond to criticism that his brother, Alexis Humala, a high-ranking member of the party, flew to Moscow to talk about energy and fishing contracts with the Russian government.

Even after his brother was suspended from the party, Humala tried to avoid personally responding to critics who accused him of nepotism.

Though he has been active on Twitter, where he has promised to crack down on crime, Humala has yet to address a controversy over the appointment of his wife's cousin to head of the national tax collection agency, at the center of efforts to grow Peru's tiny tax base and fund social programs.

Another debate has erupted about whether Peru should scrap its existing constitution -- which former President Alberto Fujimori's authoritarian government passed in 1993 -- to introduce one based on the charter of 1979.

Humala promised during the campaign to leave untouched the existing constitution, which defines Peru as a market economy and emphasizes private property rights more than the previous one.

Then, in a swipe at Fujimori's right-wing party, he said at his inauguration that he would uphold the spirit of the 1979 constitution because the existing one showed little respect for democracy.

Since then, Humala has stayed quiet as members of his cabinet and the major parties in Congress argue about whether the constitution should be reformed.

Then there is the polemical issue of whether another brother, Antauro Humala, should be released early from jail.

Antauro, a former army officer, was sentenced to 25 years in prison for leading a rebellion in 2005 to demand the resignation of former President Alejandro Toledo.

Four police officers died trying to put down the insurrection, but Antauro's defenders say he never fired a shot and only inspired the uprising.

Anything resembling a pardon or an early parole, which two of Humala's aides have expressed support for, would prompt supporters of Fujimori to demand he be freed too.

Fujimori was convicted of corruption and human rights crimes for authorizing two massacres when Peru was battling guerrilla groups in the 1990s. Freeing Fujimori would infuriate human rights activists who backed Humala during the campaign.

(Writing by Terry Wade; Editing by Kieran Murray)