In Bolivia, deforestation on the rise: The relentless push to clear-cut trees has given Bolivia the highest rate of Amazonian deforestation. Picture Gallery in original article

Amazon forest threat is greater outside Brazil

August 31, 2012 - Washington Post

By Juan Forero,

In ASCENCION, Bolivia — On a scorching afternoon in the Amazon, all Agustin Villa and his partner needed was a chain saw and gasoline to take down an 82-foot hardwood in less than two minutes.

Battling thick brush and mosquitoes, the pair downed 25 trees in all that day, from silk-cotton softwoods to figs, clearing the limbs and sawing them into sections for tractors to drag to a nearby dirt road.

Across this corner of eastern Bolivia, peasants torch the forest for subsistence crops, while soy producers clear trees to plant one of the world's great cash crops. Their relentless push, much of it legal, has given Bolivia the highest rate of Amazonian deforestation and underscored a little-known trend that environmentalists say should be a wake-up call for the world's greatest forest.

Across this corner of eastern Bolivia, peasants torch the forest for subsistence crops, while soy producers clear trees to plant one of the world's great cash crops. Their relentless push, much of it legal, has given Bolivia the highest rate of Amazonian deforestation and underscored a little-known trend that environmentalists say should be a wake-up call for the world's greatest forest.

While environmental campaigns have, for decades, focused on Brazil's Amazon, today in South America, it is the enormous expanse of Amazonian forest outside Brazil, in a moon-shaped arc from Bolivia to Colombia and east to French Guiana, that is facing its most serious threat.

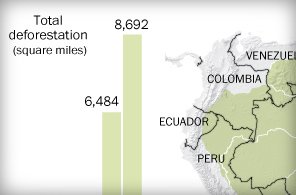

In Brazil, the enforcement of land-use laws reduced deforestation by 76 percent in eight years — from 10,424 square miles in 2004, when a swath bigger than Maryland was cleared of jungle, until last year, when the country's National Institute for Space Research reported that 2,471 square miles had been destroyed.

But more than 40 percent of the Amazon is beyond Brazil's borders, spread across eight countries in a carpet of green six times the size of California. These countries are poorer and less stable than Brazil, with less capacity to control clear-cutting of trees. Government agencies that regulate land use are spread thin, and some of those countries, including Bolivia, actively promote development in the jungle.

Satellite data and fieldwork by environmental and forestry ministries in the region show that deforestation in the non-Brazilian Amazon rose from an annual average of 1,930 square miles in the 1990s to 2,779 square miles last year.

"There's more deforestation going on in the Andean Amazon than in the Brazilian Amazon," said Timothy Killeen, a Bolivia-based ecologist and geographer who works with environmental groups and has been studying deforestation in the Amazon for 25 years. "Before, Brazilian deforestation was four times as great as in the Andean Amazon. Now the Andes has more. We're winning the battle in Brazil but losing the battle in the Amazon."

Deforestation is not increasing in every country with Amazonian forest. Indeed, recent preliminary data from Colombia and Ecuador show a reduction in clear-cutting. And in all the countries that contain a piece of the Amazon, including Brazil, more than 80 percent of the forest remains largely intact.

But in Bolivia, where the Amazon is vast but just a seventh the size of Brazil's, the amount of territory deforested annually is more than half as much as was lost in Brazil. Peru, which has a stretch of rain forest bigger than Texas, is seeing hundreds of square miles fall annually to chain saws, fires and machinery. Some of the smaller countries, such as French Guiana, have seen a dramatic spike in deforestation.

The driver of deforestation has been a commodity boom centered on exports to China and other Asian economies.

In Peru, mining and infrastructure development projects are to blame, environmentalists say, while in Ecuador, oil companies have expanded into the jungle. Small-scale farmers and moneyed producers of oil palm trees are cutting into the bush in Colombia. In the eastern shoulder of South America — Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana — artisanal gold mining is seen as a main threat.

These countries have less influence with other governments at climate-change conferences than Brazil, which has one of the world's leading economies and whose Amazonian forest is the size of Western Europe.

"Brazil is 60 percent of the area and gets maybe 90 percent of the attention," said Virgilio Viana, chief executive of the Foundation for a Sustainable Amazon, an environmental organization in Brazil's Amazon. "So the rest of the area gets less of the media attention and less of the political attention."

Environmentalists say the destruction of the Andean Amazon is particularly worrisome because it affects the lifeblood for the entire Amazon, the rivers flowing down from the Andes. The forests that reach the foothills of the Andes — in Bolivia, Peru, Colombia and Ecuador, where a change of a few hundred feet in altitude can mean entirely new plant and animal species — are the most biodiverse in the world.

"This is the richest part of the entire Amazon basin because of the climate diversity and the altitudinal diversity," said Bruce Babbitt, an environmentalist and former U.S. interior secretary who does research in the Peruvian Amazon with the Blue Moon Fund, a foundation supporting conservation. "The challenge, I think, is to see if we can sort of hold back these waves of development."

A familiar struggle

In many ways, what is happening in Bolivia is what happened in Brazil a generation ago, as farmers, ranchers and timber companies flooded in, taking advantage of cheap land, government subsidies and virgin forests.

In this slice of Bolivia north of the regional capital of Santa Cruz, a hectare of land — about 2.5 acres — can cost $1,200, while in Brazil's soybean belt it can cost $8,000 and in Argentina up to $15,000. Diesel fuel for farm machinery is subsidized by the government, and state policies are designed to encourage development, said Eduardo Forno, director of Conservation International in Bolivia.

Without access to the Pacific Coast, landlocked Bolivia also sees its fortunes in exploiting its lowlands, which cover more than half the country.

"There's a Bolivian perception that the future is in Amazonia," Forno said. "And that perception and the dynamics that go with it are leading big businessmen to embrace a vision that's leading to this deforestation."

Diego Pacheco, a negotiator for Bolivia's climate-talks team and an adviser on environmental matters to the Foreign Ministry, said the government is trying to design a policy that balances the environment with people's needs. The idea, he said, is to promote sustainable projects that keep much of the forest intact.

But Pacheco said a forestry law and a land-use law from the 1990s are at odds, with one consolidating use for land owners and the other designed to protect the wilderness.

"Without a clear policy, there is an opening for the irregular use of land," said Pacheco, explaining that much of the deforestation is illegal or takes place legally but without much thought as to the consequences.

Difficult to enforce

In the jungle outside Ascencion, a town bustling with logging trucks and stores selling farming equipment, the final arbiter on land use is the Forests and Land Agency, which provides permits to those who want to clear land and sanctions those who do so illegally.

But the agency has only 11 enforcement agents to hunt down illegal logging and clear-cutting and only a handful of others to process legal bids to deforest.

"The problem I see is ignorance of the laws. So there's clear-cutting, burning of land that takes place," said Lillian Bellot, the lawyer for the office. "People don't know they had to come here for permission."

And permission is often granted.

Much of the deforestation in this region is legal for cattle ranchers, soy farms and loggers, environmentalists say.

On a 170-acre farm north of Ascencion, Martha Zotar, 37, and her husband, Eloy Arancibia, plant mostly soybeans on legally acquired land.

On a recent day, Zotar walked amid rows of newly planted soybeans toward a batch of trees, also on the couple's land. She said her husband has suggested cutting into those, too, but she won't let him.

"I always tell my husband, 'Don't take down the trees because, later, there won't even be rain,' " she said. "And so that's where we are now. No more. We don't want to deforest all of it."