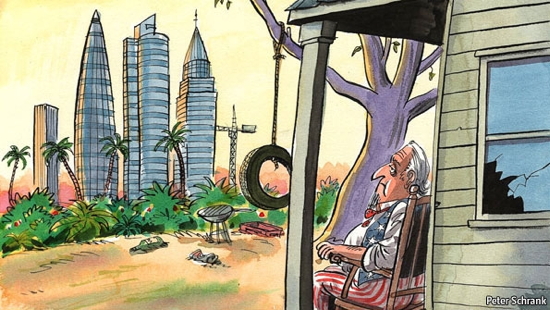

The real back yard

April 14, 2012 - Economist

An interesting reversal in the Western hemisphere

ALL in all, this is a pretty good time to be an American. Think about it. The middle class is expanding and growing richer. Once-stark inequalities are shrinking. The quality of governance has improved by leaps and bounds. Politics is becoming less ideological and more centrist and pragmatic. And never before have Americans held such sway in the wider world.

Oh, perhaps a clarification is in order. This is a pretty good time to be a Latin American. For the citizens of the United States, who tend somewhat presumptuously to think of themselves as the only Americans, this is not altogether such a good time. In the United States, in point of fact, all those trends are running in the opposite direction. The middle class is beleaguered; inequality is growing; government is gridlocked; politics is increasingly polarised and the superpower is in a funk about its global decline. Isn't this high time for the United States to pay a little more attention to the big changes taking place in its own back yard?

Put that question to an official in Washington, DC, and you will usually be told that the United States pays plenty of attention to its southern neighbours. America helps Mexico to fight drug-traffickers and Colombia to fight insurgents. Why, only this week Dilma Rousseff, the president of Brazil, was in town, meeting Barack Obama at the White House (see article). Mr Obama was due later to jet off to the Summit of the Americas in Colombia. Compared with America's scratchy relations with Russia and China, or its wars and near-wars in Afghanistan and the Middle East, or with the economic shockwaves that might cross the Atlantic from a collapsing euro zone, its relations with Latin America (Venezuela's tiresome Hugo Chávez apart) look to be ticking over nicely. No need to fix what is not broken.

That, however, is not the view of around 100 wise men and women, almost half from the United States and the rest from Canada and Latin America, including eminences such as former presidents and ambassadors, who take a glummer view in a report issued this week by the Washington-based Inter-American Dialogue, a think-tank. They say that the relatively good news from Latin America in recent years, and the relatively bad news from the United States, have damaged ties between north and south. Most countries in Latin America are coming to see the United States as "less and less relevant to their needs—and with declining capacity to propose and carry out strategies to deal with the issues that most concern them."

The danger is not so much that anything dire will happen, they say; more that if America's engagement with the region remains "listless", urgent work will be neglected and useful opportunities missed, with potentially wretched long-term consequences for the whole hemisphere. The United States needs to "better appreciate" the rising importance of Latin America, with its expanding market for the north's exports, its burgeoning investment opportunities, its enormous reserves of energy and minerals and its continuing supply of needed labour. At the same time, and despite their recent growth and globalisation, the economies of Latin America depend on the far bigger one of the United States for capital, know-how, technology and remittances.

If geography is destiny, and the United States and Latin America need one another so badly, what prevents them from consummating the romance? Here the eminent authors pinpoint three policy differences—on immigration, the war on drugs and the embargo on Cuba—that have pitted the United States against the consensus of the hemisphere's other 34 governments.

America's broken immigration system is "breeding resentment across the region", they say: Latin Americans find the idea of building a wall on the border between the United States and Mexico "particularly offensive". The north's war on drug traffickers serves mainly to spread corruption, fan criminal violence and undermine the rule of law. And as for Cuba, the embargo imposed by the United States has probably been counter-productive, prolonging the repressive rule of the Castro brothers instead of helping to end it.

These observations are hardly novel. The problem, as everyone knows, is that each of these issues is tangled in the domestic politics of the United States. In the past few years Mexico's improving economy, slowing population growth and a weak jobs market in the north have cut the flow of immigrants across the Rio Grande. Even so, immigration remained a toxic issue in the Republican Party's primaries, in which almost every candidate vied to be tougher than the next on illegal immigration. To make progress in the war on drugs, the United States needs to curb demand for illegal narcotics at home, but no American politician dare broach the idea of decriminalisation. Attempts to intercept the guns that flow south to the narco-gangs antagonise America's muscular gun-rights lobby. And Cuba policy is held hostage by the Cuban diaspora in Florida, a critical swing state.

Quit griping

From Washington, the periodic whingeing from Latin America about the lack of respect and attention the region receives from the yanquis can become wearying. If Latin America is doing so damn well all of a sudden, why does it not just get on with the business of standing on its own feet? As for the tricky issues of immigration, drugs and Cuba, can't those southerners see how things stand north of the border? Don't they understand that the thorny domestic politics of the United States make serious action on them impossible? They can see. They do understand. But in recent decades some of the countries of Latin America have managed against much greater odds to summon up the courage to overcome their own impossible domestic politics. It may be time for the United States to follow their example for a change.