Video: Cick to go to original story

for

video in at beginning of story

After Jailing Women, Bolivia Weighs Legalizing AbortionJune 24, 2013 - The Atlantic

The move would be a major step in a region with harsh restrictions on terminating pregnancies.

Gillian Kane

On January 30, 2012, Helena, a 27-year-old Guaraní Indian, was arrested and handcuffed to her bed at the Percy Boland Maternity Hospital in Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Six months earlier, she had been raped; at the time of her arrest she was 24 weeks pregnant. Helena (not her real name) was reported to police authorities by her doctor after seeking emergency treatment for obstetric complications from taking pills to end her pregnancy. She was charged with the crime of abortion. Abortion is illegal in Bolivia and lawbreakers like Helena can face up to three years in prison.

Punitive responses to crisis health needs like this play out all over Latin America, where abortion is largely illegal or highly restricted in many countries. That may soon change in Bolivia, however. The nation's top court is scheduled to meet Monday to review a constitutional challenge to the country's abortion laws and to other policies that impede women's access to a full range of human rights. A positive decision would mean that for the first time in 41 years, Bolivian women meeting certain conditions for an abortion would be free from criminal sanctions.

President Evo Morales's election in 2006 ushered in an unprecedented era of indigenous pride and rights for Bolivia. In 2009 these rights were codified in a new constitution that ranks among the more radical in the world. Based on the principles of decolonization and depatriarchialization, the constitution recognizes and protects, for the first time, Bolivia's indigenous communities and Pachamama (Mother Earth), a local term for the environment. It prohibits discrimination based on gender identity and sexual orientation, and it identifies Bolivia as a pacifist, secular state. In another first, it guarantees sexual and reproductive rights.

However, the rub lies in the implementation of the constitution: Many laws must still be revised to reflect the new rights. This includes the country's penal codes, which date to 1972. It is under these penal codes that Helena was charged and imprisoned for an illegal abortion.

"I didn't know who the father was. I was raped. I didn't want to have a child without a father."

Given the legal disconnect between the new constitution and the old penal codes, Deputy Patricia Mancilla, a recently elected indigenous member of the country's congress, presented a legal challenge questioning the constitutionality of several articles related to women's issues. This included Article 263, which criminalizes abortion. Another article highlighted reduces criminal penalties by half if a man claims his crime was committed to preserve a woman's honor. And yet another sanctions a man who abandons a pregnant woman outside of marriage, but not a man who abandons his wife and children. In one of the more antediluvian articles, a rapist can avoid criminal sanctions if he marries his victim.

The court's ruling on abortion, and the eleven other articles presented by Mancilla, could have an immediate effect on women's access to health services. This is particularly true in the case of abortion if the court eliminates the need to request judicial authorization for the procedure, perhaps the biggest barrier to accessing legal abortions in the country.

***

Deputy Mancilla is an Aymara Indian. She attends congressional meetings wearing the traditional dress of her community: a long skirt blooming over multicolored layers of petticoats and a small grey bowler hat delicately balanced on two long plaits trailing down her back. This is Mancilla's first foray into politics and is evidence of Evo's successful efforts to diversify the congress to more accurately represent the country, both based on gender and ethnicity.

Soft spoken and circumspect, Mancilla explains she was motivated to launch her challenge "because of the deaths of so many women as a result of our country's underdevelopment. With the new constitution we are now able to modify laws, codes, and policies and improve our society for the wellbeing of Bolivian women."

Percy Boland Hospital, where Helena was arrested, is located in the lowland city of Santa Cruz, one of the fastest-growing cities in the world. Named after a firebrand second-generation Irish immigrant, Percy Boland is the lead teaching hospital in the country, with 154 beds and an average of 1,000 births per month. Boland's family settled in Santa Cruz in 1912 and they are locally recognized for their contributions to turning the backwater town into Bolivia's largest city. Boland, a Harvard graduate, was the founding member of the Bolivian Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology and was dedicated to improving and modernizing maternity hospital care for Cruceña women.

But urban modernization isn't always accompanied by improved health services; a third of all maternal deaths in Bolivia are due to unsafe abortion. From 2010-2011 the rate of women reporting to Percy Boland Hospital for complications from unsafe abortions rose from 4,174 to 4,709. According to 2011 statistics from the Bolivian Ministry of Health, an estimated 67,000 abortions -- mostly illegal and unsafe -- were performed in the country. Almost half of the women who have abortions in Bolivia end up needing post-abortion emergency care.

Helena was one of those women. She was the only one to go to prison.

When Helena arrived at the Percy Boland Maternity Hospital last January, she was raising one child on her own. She had no criminal record. Helena worked two jobs, one at a local pastry shop, located in front of the Palace of Justice, a second as a waitress, which netted her $130 a month. With the exception of a work colleague, Helena never told anyone that she'd been raped or that she was pregnant as a result. Helena explained she wanted the abortion "because I didn't know who the father was. I was raped. I didn't want to have a child without a father." She never reported the rape to the police.

Sexual violence is endemic in Bolivia; after Haiti it has the highest rates of sexual violence in Latin America. According to UN Women, seven out of 10 women in Bolivia are victims of sexual violence. The majority of the crimes are perpetrated by a male family member.

Even the halls of the congress are not safe. In January, a widely circulated security video showed a member of the Chuquisaca State Congress allegedly raping one of the cleaning staff--in one of the congress's meeting rooms.

Elizabeth Salguero, a former congresswoman and currently Bolivia's ambassador to Germany, is a longtime activist for women's and indigenous rights and is all too familiar with the issue and personally knows "not just women but also little girls, adolescents (who have been raped). I have also seen the sense of relief that follows after they get an abortion for a pregnancy that results from sexual violence."

In theory, under the current penal codes Helena, as a rape survivor, could have obtained a legal abortion. However, first she would have to report the rape to the police. Then, once the filing was complete she would need to go to court to request and receive judicial authorization. Even if Helena was aware of these legal options and had followed them, it is very unlikely she would have received a legal abortion. A recent investigation by Ipas reviewed judicial records in the cities of La Paz and Santa Cruz and found that from 2006 to the present, only one legal abortion was approved by a judge.

***

After Helena delivered the fetus at the hospital, she was handcuffed and apprehended. The fetus was taken by the Homicide Division of the Special Crimes Unit. For the ten days she was in the hospital recovering from the unsafe abortion, she was held in police custody. A police investigation determined that Helena's work colleague had purchased the pills used for the abortion. The police raided several pharmacies for selling the drug misoprostol without a prescription. No one was arrested.

Documents collected from the Santa Cruz public prosecutor's office dating from 2008 show that 80 cases of illegal abortions were recorded. With the exception of Helena's case, none ended in a prison term. They were dropped either because the accuser -- generally the public prosecutor or a health provider -- didn't follow up or because the police or the judicial system did not take action.

On February 3, 2012, Helena was formally charged, but not sentenced. Despite having no previous criminal record, the prosecutor deemed Helena a flight risk and placed her in preventive detention in Santa Cruz's Palmasola prison. Helena's public defender appealed the detention order, but it was denied.

Palmasola is infamous for its poor conditions and overcrowding. Recently it has gained attention for incarcerating Jacob Ostreicher, a U.S. citizen accused of drug laundering whose case has been championed by actor Sean Penn. Penn testified last month on behalf of Ostreicher before the House Foreign Affairs' Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights and International Organizations. He called Palmasola a "modern day Dante's Inferno" and criticized " the fundamentally corrupt Bolivian Judiciary."

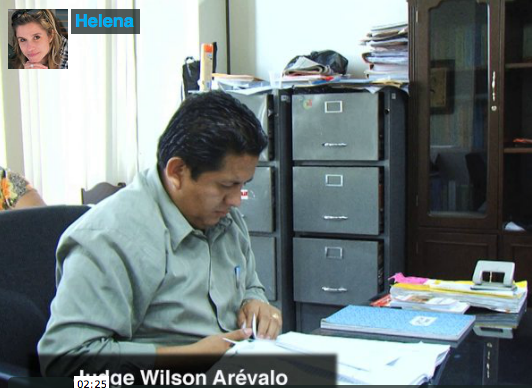

And indeed, Bolivia's judiciary suffers from a lack of transparency. Justice is parsed erratically, in part because of questionable judges. Helena and Ostericher shared the same judge, Wilson Arévalo. In January Arévalo was indicted for dereliction of duty and was implicated as part of a wide extortion ring. Two months after Helena's case was closed, Arévalo was fined and sentenced to house arrest.

After a months long series of baroque events--hearings were scheduled and cancelled; Helena's public defender would neglect to show up or the judge would fail to show--Helena pleaded guilty to the crime of abortion. She was sentenced to two years of prison. Bolivian legislation permits the option to serve a sentence outside of prison if a judicial pardon is requested. Helena requested and was granted the pardon. After eight months, on October 17, following various administrative complications, Helena was freed from Palmasola prison.

According to Bernardo Wayar , ex-president of the Law University, if the court agrees with Deputy Mancilla's claim that twelve articles of the penal codes are unconstitutional, abortion would be decriminalized in Bolivia. This would be a much welcome decision not just in Bolivia, but the region as a whole. Where abortion is criminalized, women are forced to seek out unsafe services to end an unwanted pregnancy. In places like El Salvador, where abortion is outlawed completely, this has significant health and penal consequences. Two weeks ago in El Salvador, after almost three months of waiting, a woman pregnant with a non-viable fetus and suffering from a life-threatening disease was denied a therapeutic abortion by the country's top court. The Bolivian Constitutional Court's decision could strengthen the legal debate in favor of abortion reform in El Salvador and other countries in Latin America with extreme restrictions on abortion.