(above) A Bolivian quinoa farmer. (Vitaliy Prokopets/Pictilio.com

Quinoa should be taking over the world. This is why it isn't.

July 11, 2013 - Washington Post

By Lydia DePillis,

In the Andean highlands of Bolivia and Peru, the broom-like, purple-flowered goosefoot plant is spreading over the barren hillsides–further and further every spring. When it's dried, threshed, and processed through special machines, the plant yields a golden stream of seeds called quinoa, a protein-rich foodstuff that's been a staple of poor communities here for millennia. Now, quinoa exports have brought cash raining down on the dry land, which farmers have converted into new clothes, richer diets, and shiny vehicles.

But at the moment, the Andeans aren't supplying enough of the ancient grain. A few thousand miles north, at a downtown Washington D.C. outlet of the fast-casual Freshii chain one recent evening, a sign delivered unpleasant news: "As a result of issues beyond Freshii's control, Quinoa is not available." Strong worldwide demand, the sign explained, had led to a shortage. A Freshii spokeswoman said that prices had suddenly spiked, and the company gave franchises the choice to either eat the cost or pull the ingredient while they renegotiated their contract.

Quinoa is a low-calorie, gluten-free, high-protein grain that tastes great. Its popularity has exploded in the last several years, particularly among affluent, health-conscious Americans. But the kinks that kept the grain out of Freshii that day are emblematic of the hurdles it will face to becoming a truly widespread global commodity and a major part of Americans' diet. It shows the crucial role of global agribusiness, big-ticket infrastructure investment, and trade in bringing us the things we eat, whether we like it or not.

In short, it's hard to keep something on the menu if you might not be able to afford it the next day. And the American agricultural economy makes it hard for a new product to reach the kind of steady prices and day-in-day-out supply that it takes to make it big.

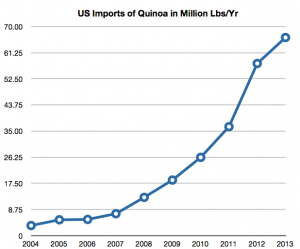

Chart1 Quinoa imports, skyrocketing. (U.S. Customs data)

Chart1 Quinoa imports, skyrocketing. (U.S. Customs data)

A grain whose time has come

Quinoa went extinct in the United States long before upscale lunch places started putting it in side salads. Agronomists have found evidence of its cultivation in the Mississippi Valley dating back to the first millennium AD, but it faded away after farmers opted for higher-yielding corn, squash, and bean crops.

Enthusiasts started growing quinoa again in the 1980s, mostly in the mountains of Colorado. It's not easy, though–sometimes it takes several seasons to get any harvest, since seeds can crack, get overtaken by weeds, or die off because of excessive heat or cold. In 2012, the U.S. accounted for a negligible amount of the 200 million pounds produced worldwide, with more than 90 percent coming from Bolivia and Peru.

Demand started to ramp up in 2007, when Customs data show that the U.S. imported 7.3 million pounds of quinoa. Costco, Trader Joe's, and Whole Foods began carrying the seed soon after, and the U.S. bought 57.6 million pounds in 2012, with 2013 imports projected at 68 million pounds. And yet, prices are skyrocketing; they tripled between 2006 and 2011, and now hover between $4.50 and $8 per pound on the shelf.

What's driving the increase? Part of it is that Peru itself, already the world's biggest consumer of quinoa, patriotically started including the stuff in school lunch subsidies and maternal welfare programs. Then there's the United Nations, which declared 2013 the International Year of Quinoa, partly in order to raise awareness of the crop beyond its traditional roots.

But it's also about the demographics of the end-user in developed countries–the kind of people who don't think twice about paying five bucks for a little box of something with such good-for-you buzz. A few blocks away from Freshii in Washington D.C. is the Protein Bar, a four-year-old Chicago-based chain that uses between 75 and 100 pounds of quinoa per week in its stores for salads and bowls that run from $6 to $10 each (Their slogan: "We do healthy…healthier").

Right now, the company has so far decided to absorb the higher prices, which still aren't as much of a cost factor as beef and chicken. It will even pay a little extra to ship the good stuff from South America, rather than the grainier variety that Canada has developed.

"As much as I don't like it–you never want to pay more for your raw materials–it's central to our menu," says CEO Matt Matros. "I'm pretty positive that as the world catches on to what a great product is, the supply will go up and the price will come back down. It'll come down to the best product for us. If we find that the American quinoa is as fluffy, then we'll definitely make the switch."

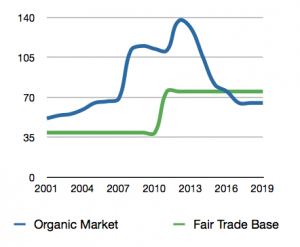

Chart 2 Andean Naturals predicts quinoa prices will drop, and wants to establish a fair trade price floor to help sustain small farmers. (Andean Naturals)

Chart 2 Andean Naturals predicts quinoa prices will drop, and wants to establish a fair trade price floor to help sustain small farmers. (Andean Naturals)

Cracking the quinoa code

The Andean smallholders are trying to keep up with the demand. They've put more and more land into quinoa in recent years; Bolivia had 400 square miles under cultivation last year, up from 240 in 2009. The arid, cool land that quinoa needs was plentiful, since little else could grow there. And thus far, that trait has made it difficult to grow elsewhere.

But that doesn't mean the rest of the world isn't trying. A Peruvian university has developed a variety that will grow in coastal climates. There are also promising breeding programs in Argentina, Ecuador, Denmark, Chile, and Pakistan. Washington State University has been developing varieties for cultivation in the Pacific Northwest, and in August will hold a quinoa symposium bringing together researchers from all over to talk about their work.

"To me, the imagination is the limit, and a whole lot of effort," says Rick Jellen, chair of the plant and wildlife sciences department at Brigham Young University. "Quinoa is a plant that produces a tremendous amount of seed. So you have potential, with intensive selection, to identify variants that have unusual characteristics."

The South American quinoa industry, and the importers who care about it, are worried about the coming worldwide explosion of their native crop. Despite a bubble of media coverage earlier this year about how strong demand is making it difficult for Bolivians to afford to eat what they grow, it's also boosted incomes from about $35 per family per month to about $220, boosting their standards of living dramatically. Now, the worry is maintaining a steady income level when production takes off around the world.

Sergio Nunez de Arco, a native Bolivian who in 2004 helped found an import company called Andean Naturals in California, likes to show the small-scale farmers he buys from pictures of quinoa trucks in Canada to prove that the rest of the world is gaining on them, and that they need to invest in better equipment. Meanwhile, he's trying to develop awareness about the importance of quinoa to reducing poverty, so that they can charge a fair trade price when the quinoa glut comes.

"The market has this natural tendency to commoditize things. There's no longer a face, a place, it's just quinoa," de Arco says. "We're at this inflection point where we want people to know where their quinoa is coming from, and the consumer actually is willing to pay them a little more so they do put their kids through school."

He's even helping a couple of Bolivian farmers who don't speak English very well fly to that Washington State University conference, so they'll at least be represented.

"It kind of hurts that the guys who've been doing this for 4,000 years aren't even present," de Arco says. "'You guys are awesome, but your stuff is antiquated, so move over, a new age of quinoa is coming.'"

(right) Bolivian quinoa processing. (Vitaliy Prokopets, Pictilio.com)

(right) Bolivian quinoa processing. (Vitaliy Prokopets, Pictilio.com)

Why isn't the U.S. growing more of it?

So far, though, the mystery is why the new age of quinoa is taking so long to arrive.

Americans have been aware of the crop for decades, and used to produce 37 percent of the world supply, according to former Colorado state agronomist Duane Johnson. It never took off, partly because of pressure from advocates of indigenous farmers–in the 1990s, Colorado State University researchers received a patent on a quinoa variety, but dropped it after Bolivian producers protested it would destroy their livelihoods.

You don't need a patent to grow a crop, of course. But the switching cost is extremely high, says Cynthia Harriman of the Whole Grains Council. "Can you get a loan from your bank, when the loan officer knows nothing about quinoa? Will he or she say, 'stick to soybeans or corn?'" It even requires different kinds of transportation equipment. "If you grow quinoa up in the high Rockies, where are the rail cars that can haul away your crop? Or the roads suitable for large trucks?"

All that infrastructure costs money, and the only farmers with lots of money are in industrial agribusiness. But U.S. industry has shown little interest in developing the ancient grain. Kellogg uses quinoa in one granola bar, and PepsiCo's Quaker Oats owns a quinoa brand, but the biggest grain processors–Cargill and Archer Daniels Midland–say they've got no plans to start sourcing it. Monsanto, the world's largest seed producer, has nothing either.

Instead, their research and development dollars are focused entirely on developing newer, more pest-resistant forms of corn, soybeans, wheat, sugar, and other staples. All of those crops have their own corporate lobbying associations, government subsidy programs, and academic departments devoted to maintaining production and consumption. Against that, a few researchers and independent farmers trying to increase quinoa supply don't have much of a chance.

"This is something where it would truly have to come from the demand side–no one wants to get into this and get stuck with all this excess inventory," says Marc Bellemare, an agricultural economist at Duke University. And how do you determine how much demand is enough, or whether a fad has staying power? "We still haven't fully unbundled what the decision bundle is. It's like shining a flashlight in a big dark room."

That's why it's hard for any new crop to make the transition from niche to mainstream. Products, maybe: Soy milk is ubiquitous now, after years as a marginal hippie thing, but it comes from a plant that U.S. farmers have grown for decades. An entirely new species is something else altogether. "I wouldn't even go so far as to say that's a non-staple that went big-time," Bellemare says.

For that reason, quinoa prices are likely to remain volatile for a long while yet. Brigham Young's Rick Jellen says the lack of research funding for quinoa–relative to the other large crop programs–means that even if they come up with a more versatile strain, it won't have the resilience to survive an infestation.

"Once that production moves down to a more benign environment, you're going to get three or four years of very good production," he predicts. "And then you're going to hit a wall, you're going to have a pest come in, and it's going to wreak havoc on the crop. I think we're going to see big fluctuations in quinoa prices until someone with money has the vision and is willing to take the risk to invest to really start a long-term breeding program for the crop."

Which means that if you're looking forward to a quinoa lunch in downtown D.C., be prepared for a disappointment.