Held to a Different Standard: The US Decertifies Bolivia

September 20, 2013 - Andean Information Network (AIN)

Written by the Andean Information Network, September 20, 2013

All cocaine-producing countries are equal; but some are more equal than others.

The White House's decision to "decertify" Bolivia's drug control efforts for the sixth time is no surprise. Since Bolivian President Evo Morales expelled the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in 2008, the US has portrayed Bolivia as uncooperative and incapable of curtailing illicit drug production and trafficking. The White House's corresponding Memorandum of Justification lacks objectivity and attempts to hold Bolivia to higher standards than Peru and Colombia (which are both fully certified), or even the US. As a result, as in previous years, it fails to acknowledge that although problems persist, Bolivia has made steady progress in drug control according to the US's own yardsticks.

Some of the most glaring contradictions and inaccuracies presented include:

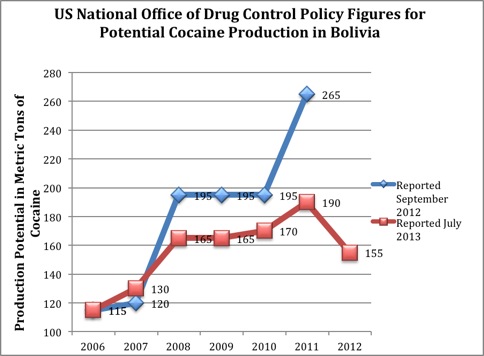

- Last year's inaccurate determination pointed to a whopping 36% increase in potential cocaine production from 2010 to 2011 as a key cause for decertification. Yet, the US figure reported for 2012 potential production is 41% lower –a dramatic reduction; although the Memorandum only cites an 18% drop, there is no explanation provided for the dramatic rise and fall in figures. The Memorandum calls this supposed dramatic change an "incremental positive step," compared to what they characterize as Bolivia's "overall negative counternarcotics performance."

- Accusations that Bolivia does not comply with United Nations drug regulations highlight the selective arguments employed in the justification, given that the US directly violates the UN Single Convention with legalization of marijuana in two states.

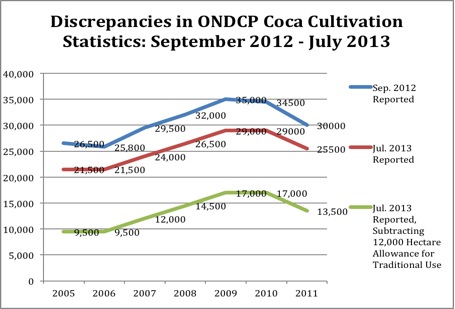

- The US accusation that the Bolivian government has a "disinclination to be transparent with the international community" is ironic. The US government does not explain its methodology to arrive at estimates for coca and potential cocaine production. Furthermore, between September 2012 and July 2013, the US retroactively changed its statistics for potential cocaine production and estimated coca cultivation for Bolivia and Colombia without any explanation to the international community.

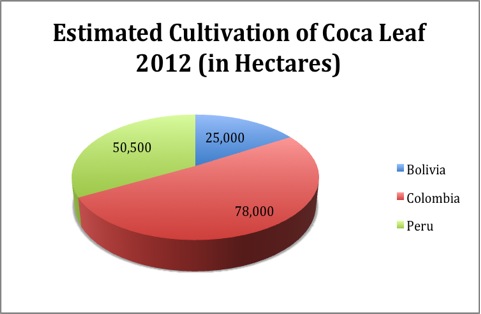

Even after the expulsion of the DEA and the precipitous drop in aid money from the US, Bolivia has reduced coca leaf cultivation and potential cocaine production, and increased seizures and destruction of cocaine laboratories. The Presidential Determination seems particularly unfair considering the only other coca-producing countries, Peru and Colombia, produce far more coca and cocaine (in spite of their close cooperation with the DEA).

Source: US White House

Comments on Memorandum of Justification

Sections from the Memorandum of Justification are in the highlighted boxes.

Bolivia's ability to interdict drugs and major traffickers was seriously compromised by its 2009 expulsion of U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) personnel, harming its ability to conduct counternarcotics operations and cooperate on international illicit drug interdiction.

The illegal drug trade continues in Latin American countries where the DEA continues to operate, just as it did during 35 years of DEA presence in Bolivia. The US places selective blame on Bolivia, suggesting that collaboration with the DEA is indispensible. For example, Peru cultivates more than twice as much coca leaf as Bolivia does, and has 145 metric tons more cocaine production potential—almost double Bolivia's—all the while cooperating with the DEA. A great deal of comparatively inexpensive Peruvian cocaine paste comes through Bolivia, not because the Bolivians are permissive, but because coca leaf costs half as much in Peru.

The DEA highlights its key role in intelligence exchange between countries, and the US claims that since its expulsion, Bolivia has become "a convenient venue for drug smuggling." It is time to step back from that reasoning. Beyond resentment for the expulsion, there is no impediment to intelligence exchange, and Bolivia would readily accept it. Instead, drug control officials in neighboring countries argue that the DEA blocks these exchanges in spite of their intelligence-sharing agreements Bolivia. Furthermore, it would be naïve to think that the DEA has no intelligence capacity in Bolivia. The DEA has access to the Brazilian drone surveillance of potential trafficking sites and coca fields. At least one long-term DEA officer stayed on in Bolivia after the agency's expulsion as regional director for the US Narcotic Affairs Section. According to one analyst, "What strikes me is the US desire to punish Bolivia for not keeping with the program, as opposed to giving credit where it's due and mitigating harm (such as through sharing intelligence) where it's needed."[i]

US Fiddles with Figures: Cites Only "Incremental Positive Steps in Coca Control"

The 2012 United States Government coca cultivation estimate for Bolivia is 25,000 hectares, a 2 percent decrease from the 2011 estimate of 25,500 hectares.

There is actually a 17% decrease in the amount of coca cultivation reported by the Obama administration for 2011 in 2012 (30,000 hectares) and the figure reported in 2013. The administration quietly reduced coca cultivation estimates for the previous five years[ii] without explanation or noting the reduction. A similar shift occurred in the potential cocaine production statistics. (Note: according to Law 1008, the anti-drug law passed in 1988 under extreme pressure from the US, 12,000 hectares of coca are allowed for licit, traditional use.)

Source: US White House

Source: US White House

[Bolivia] failed to develop and execute a national drug control strategy.

A copy of the Bolivian Strategy to Fight Drug Trafficking and Reduce Surplus Coca Leaf Cultivation 2011-2015 is available on the Organization of American States website.

…This reservation encourages coca growth and adds to the complication of distinguishing between illegally and legally grown coca.

In fact, in 2011, the year Bolivia withdrew from the UN Single Convention, the US registered a 13% drop in the coca crop, a trend that continued in 2012. The reservation merely validates the status quo in Bolivia, and there is no indication that it will increase production. Furthermore, Bolivia has a complex monitoring system that benefits from direct participation from coca farmers and collaboration with the UN, the US, the European Union, and Brazil, and the system provides the most accurate estimates in the Andes[iii]

The United States remains concerned about Bolivia's intent by this action to limit, redefine, and circumvent the scope and control for illegal substances as they appear in the UN Schedule I list of narcotics.

Bolivia's withdrawal and reentry to the Convention followed established Convention guidelines. The 15 objections from UN member countries fell far short of the 60 votes required to impede the initiative. As a result, Bolivia re-entered the convention as a full member.

This is a textbook case of "the pot calling the kettle black." The US also currently violates the stipulations of the UN Single Convention. In November 2012, two US states, Colorado and Washington, legalized marijuana, also included in the UN Schedule I list. In August 2013. "The United States—architect and major proponent of the prohibitionist UN drug control treaties—is rightly choosing not to block the state-level implementation of legal, regulated marijuana markets." According to John Walsh of WOLA.

The European Union provided funding for the completion of a study to identify the amount of legal cultivation needed to support traditional coca consumption. The unwillingness of the Bolivian government to share this report in a timely way demonstrates its disinclination to be transparent with the international community.

Although the long-delayed results of the coca study have been a source of substantial friction with the international community, this does not indicate a lack of transparency on other drug control issues. For example:

- In January 2012, the US, Bolivia, and Brazil signed a trilateral agreement to improve "Bolivia's ability to measure excess coca cultivation and verify progress in meeting coca eradication targets." President Obama called the project, which began in March 2012, "the kind of regional cooperation we need." The US Embassy in La Paz noted, "The use of this technology combined with the presence of Brazil and United States as parties and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime as a project participant will make the reported amount of hectares eradicated more transparent and precise.

- The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime recognizes "close collaboration and information exchange between UNODC and the Government of Bolivia" for its coca monitoring study.

- In August 2013, a European Union representative stated, "We're very satisfied with the cooperation in the work we are doing with our Bolivian partners, " and added that "it is possible to trace every euro of assistance from its origin to its beneficiary." He highlighted that the EU planned to increase its funding to Bolivia by 17%.

While Bolivia continues lo make drug seizures and arrests of implicated individuals, the Bolivian judicial system is not adequately processing these cases to completion.

Bolivian law requires that an arrestee be formally charged within 18 months of arrest. An overwhelming majority of the incarcerated population in Bolivia, however, has not been formally charged in accordance with Bolivian law. The number of individuals who have been convicted and sentenced on drug charges in Bolivia has remained stagnant over the last several years and has not increased in proportion of the number of arrests.

Unlike many statements, this one is painfully true. However, the White House fails to mention that Bolivian judicial delay and prison overcrowding have their root in Law 1008, the strict anti-narcotics law that the US obligated Bolivia to pass in 1988. Please see AIN updates (Bolivian Prison Deaths Highlight Flaws in Judicial and Penitentiary Systems and Prison Detainees in Bolivia: Bad Fruit in a Slow Judiciary System) as well as this report by Puente Investigación Enlace (Bolivia y la retardación de justicia en procesos de la ley antidrogas "1.008") for more analysis and information.

Conclusion

In conclusion, although the Presidential Determination is disappointing, Bolivia's decertification does not come as a surprise given the US government's seeming unwillingness to recognize Bolivia's drug control efforts. The determination continues the trend of politicized reporting on drug control in the Andean region, and it is a failure by the White House to provide internal consistency. The determination is perhaps most discouraging considering the efforts Bolivian government has made in drug control, including the implementation of innovative, collaborative, conflict reduction strategies such as community coca control. The determination continues the trend of subjective reporting on drug control in the Andean region. It further erodes US credibility in the international community, and reinforces the urgency of reform US international drug policy to accompany encouraging developments in domestic efforts.

---------------------

Footnotes

[i] Email correspondence, September 18, 2013.

[ii] For example, Digprococa, the Bolivian government agency in charge of planning coca reduction, requires each coca-growing family to legally register their coca plot with the agency. The agency verifies each property and enters the coordinates of permitted coca (1600 m2 in the Chapare and 2500m2 in Yungas) with GPS into a database that is shared with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the Bolivian Social Control Program, and other organizations. US assistance through a trilateral agreement with Brazil and Bolivia signed in January provided funding for additional GPS's and laser distance meters. The European Union-funded Social Control Support Program (PACS) concluded a biometric licensing and registration of coca growers in 2012, which provided detailed information for a complex database of legal coca growers.[ii] In order to cross-reference information on registered growers, the EU also funded a program that provided government titles all to legal coca-growing properties and properties in regions where coca cultivation has expanded without authorization.