(above) President Evo Morales claims he has 'refounded' Bolivia ©Noah Friedman-Rudovsky

Evo Morales: president, or president for life?

October 26, 2015 - ft.com

Andres Schipani

When Evo Morales was a poor youngster herding llamas on the shores of Lake Poopó on Bolivia's high plains, he learnt three basic Andean rules of life: ama sua (be not a thief), ama quella (be not lazy) and ama llulla (be not a liar).

When I met him in Bolivia a few weeks ago he agreed that, as he grew into adulthood, he learnt one more rule: ama llunk'u (do not be servile). It is a maxim that has served him well: supporters of the country's first indigenous leader regard him as the man who ended five centuries of oppression against Bolivia's Amerindian peoples

Morales' rise to power has spurred hopes of radical change among the peasant farmers, unions and urban migrants who are his political base. "I have to be careful now: there are a lot of sycophants around," he says.

His party, the Movement Towards Socialism (MAS), wants him to run for a fourth term in 2019; last month Congress voted to amend the constitution to allow him to do so. A referendum to ratify that will be held next February, which is worrying to those who identify autocratic leanings in the president.

Thousands marched through La Paz in August demanding Morales be able to continue his revolution indefinitely. When I met him, I watched about 12,000 indigenous people chanting "Brother Evo, Brother Evo" as he unveiled a bust of himself at a new $11m sports complex named in his honour, in Quillacollo on the outskirts of Cochabamba.

Before he set off to the football pitch at the complex, his tone was cheerful but measured. Morales is a confident man: as far as he is concerned he has "refounded" a country whose history has been one of exclusion, hyperinflation (notably in 1985), dictatorships, coups and indigenous uprisings.

Before he set off to the football pitch at the complex, his tone was cheerful but measured. Morales is a confident man: as far as he is concerned he has "refounded" a country whose history has been one of exclusion, hyperinflation (notably in 1985), dictatorships, coups and indigenous uprisings.

"Before, we had a colonial state with a small dominant class," he said. "It was a state in name only — those were impostor presidents."

The revolving doors of the presidency spun out five office-holders in the five years before Morales won his first term in 2005, securing en masse an indigenous vote that was weary of a discredited political system. Morales also profited from indigenous anger at a US-led push to eradicate coca — cocaine's raw ingredient but traditionally used as a mild stimulant by Andeans.

He has brought a substantial measure of stability to one of Latin America's most volatile countries. He has granted sweeping rights to the Amerindian majority — serfdom was abolished only in 1945 and until 1952 indigenous people were forbidden to enter the square outside the presidential palace.

"Before Evo, we, the indigenous, were invisible," says Celima Torrico, a Quechua woman who served as justice minister during Morales' first term. "People called us 'Indians'; they used to tell us we had to first civilise ourselves before we could enter a public building."

It was Morales' connection with peasants such as Torrico that secured his first presidential term in 2005 with 54 per cent of the vote, then strengthened his support in 2009 to 63 per cent after the constitution was changed to allow immediate re-election. In 2014, he managed 61 per cent.

These emphatic victories — and a buoyant economy led by a commodities supercycle — have made him arguably the region's most successful socialist president ever. His redistributionist policies have improved living standards in one of the region's poorest nations and have gone a long way to dissolving enmity between opposing camps. Even secessionist calls in some pockets of the eastern lowlands have melted away.

"The Morales of the first term was more attentive to the internal political conflict that put Bolivia on the edge," says Martín Sívak, an Argentine journalist and author of Evo Morales: The Extraordinary Rise of the First Indigenous President of Bolivia. "Morales now is more attentive to how the economy goes, which is interesting, considering he arrived at the presidency without knowing what generated inflation."

Morales' anti-capitalist rhetoric remains fierce. Yet his macroeconomic and fiscal policies, and improved relations with the country's private sector, have fed his success. Booming gas supplies to Argentina and Brazil, coupled with mineral exports, helped to sustain average economic growth in Bolivia of 5.1 per cent a year after Morales took office in 2006.

Morales' anti-capitalist rhetoric remains fierce. Yet his macroeconomic and fiscal policies, and improved relations with the country's private sector, have fed his success. Booming gas supplies to Argentina and Brazil, coupled with mineral exports, helped to sustain average economic growth in Bolivia of 5.1 per cent a year after Morales took office in 2006.

By nationalising the hydrocarbons sector to boost state revenues and fuel a consumer boom, Bolivia's public spending has been characterised by largesse. The country has its first telecommunications satellite, and in La Paz a mass-transit cable-car system is in line for a $400m expansion.

"Some said Bolivia was dying but the state should not participate in the national economy," Morales says, referring to 1985's hyperinflation. "Now, we are better than before and better than other Latin American countries."

Moreover, a poll in August by Ipsos Bolivia put his approval ratings at 70 per cent. The flipside to some is that 54 per cent of those questioned supported a change in the constitution to allow another term for the man who entered politics as a coca trade unionist in the tropics of El Chapare.

"I come from extreme poverty and moved to El Chapare to survive, not to become president," Morales says. "After so many marches I've arrived at the presidency without expecting it. And that the people ask for my ratification is something unprecedented, historic, so I will always be subject to the will of the people."

MAS is a strong force, though less popular than its leader, and is pushing ahead with the referendum. Yet here is where many believe the peasant president will fall flat.

As dissatisfaction mounts while the commodity bonanza shrinks, the divided opposition may manage to unite against a common cause. "Evo will win but by a much smaller margin than in previous elections," says a senior MAS member. "Here is where Evo's exceptionality will fade away."

Even if Bolivia's natural resources-driven economy can ride out the end of the commodities boom, government revenues from gas exports are on course to fall by 30 per cent this year alone.

"I am not worried at all about the economy," Morales tells me. But even with almost 50 per cent of GDP stocked in foreign reserves and a $48bn projected investment plan to keep the economy humming, any collapse in income would cripple his ability to spend on satisfying the demands of his key voter bases.

"He won't have the consensus he had when the economy was stronger," says Fernando Molina, a commentator and columnist. "His power base is now more middle-class than peasant, so he needs more economy than revolution."

Some fear less money also means less democracy and a crackdown on dissent. Facing declining incomes, the president who pledged to protect the Pachamama, or Mother Earth, has opened up seven of Bolivia's 22 protected areas for hydrocarbon exploration, dismissing criticism.

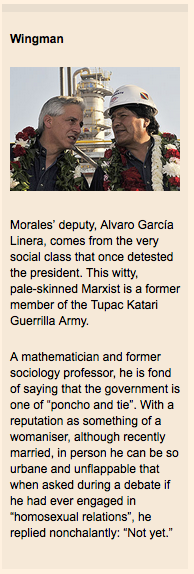

Marco Gandarillas, executive director of the Bolivian Centre for Documentation and Information (Cedib), says "democracy is turning into a problem" as it challenges these exploration plans. The organisation has been reprimanded for criticising the government; vice-president Alvaro García Linera even called it a body of "green Trotskyites".

These attitudes are alienating a swath of the president's political base, with some voicing environmental and other concerns. "He has betrayed the indigenous movement and the people," says Alejandro Almaráz, a former deputy land minister who has distanced himself from Morales.

These attitudes are alienating a swath of the president's political base, with some voicing environmental and other concerns. "He has betrayed the indigenous movement and the people," says Alejandro Almaráz, a former deputy land minister who has distanced himself from Morales.

Such a climate is raising fears of a tilt towards autocracy. The government has even admitted it has restricted its advertising through certain critical media outlets, while a cult of personality around Morales is growing amid the lack of a serious challenger. "The personalisation of the so-called process of change is one of its greatest weaknesses," warns Sívak, the Argentine journalist.

Félix Patzi, opposition governor of La Paz, was Morales' education minister but resigned from the MAS in 2010. He left, he says, when he realised "there was a sort of authoritarianism based on the idea of one person staying eternally in power".

In one mistimed incident, the president was caught on a smartphone camera asking one of his aides to tie his shoelaces up. "Morales feels he is the country's patron," says Samuel Doria Medina, a businessman and politician who ran for president against him three times.

Still, the senior MAS member believes Morales "is the only element of cohesion of indigenous, peasant and social movements, and there is a strong belief that he is the only one who could manage this country".

Not a few capitalists believe that too. "We should be thankful we have Evo. Marginalisation was a time-bomb and he has forced us to share the pie," says a businessman who did not want to be named. "The government may be controlling, with democratic failures, but here we may need that to have stability. People are willing to sacrifice some democracy for more economic autonomy."

Not a few capitalists believe that too. "We should be thankful we have Evo. Marginalisation was a time-bomb and he has forced us to share the pie," says a businessman who did not want to be named. "The government may be controlling, with democratic failures, but here we may need that to have stability. People are willing to sacrifice some democracy for more economic autonomy."

On his way to the football pitch, Morales shrugs off criticism that he is a "dictator, an authoritarian". "I have to deal with people calling me that," he says. "I reply with hard work. The opposition should not be bothered, as there is nothing more democratic than asking the people through a referendum. "If the people say no, I'll leave happily. If they say yes, I'll contribute with the experience I've accumulated so far."

Wearing the number 10 shirt, he leads the presidential team to a crushing victory over the local side led by an opposition mayor. His cheering supporters brandish banners reading "Evo 2020-2025".

As the president looks to add to a hat-trick, the commentator yells, "Morales wants more! Isn't he satisfied yet?"

As his fourth goal goes in, it would seem not.