Why people dressed as zebras dance in the streets of La Paz

December 18, 2017 - citiscope.org

LA PAZ, Bolivia — Young people dressed up in zebra costumes careen through the halls of an office building here, cheering and high-fiving each other as they got ready for work.

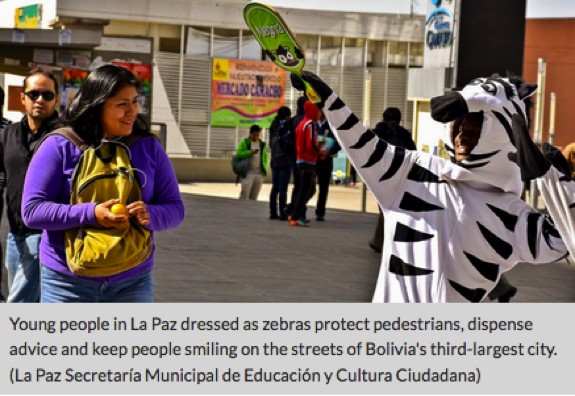

It's the morning rush hour in this bustling city of almost a million people. And this beloved herd of mascots will soon disperse into the chaotic, traffic-clogged streets to protect pedestrians, keep order on the sidewalks and offer passersby some occasional advice. Dressed as zebras.

They're sanctioned by city authorities to do this. Today, 265 teenagers and young adults make up the zebra programme. It's a city-funded initiative that trains youth from broken homes or financially troubled backgrounds to become public ambassadors for everything from good driving to good dietary habits. The costumes are a play on the phrase "zebra crossings" — the striped crosswalks where pedestrians here often must dodge cars and motorbikes to cross the street.

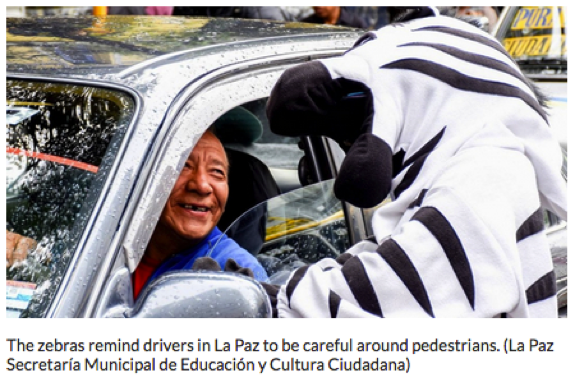

To be a zebra is to be a street clown with a social purpose. They post up on street corners and wave placards shaped like stop signs with phrases like "Love" and "Respect". They dance and skip as they usher pedestrians along the crosswalk. And they gesture wildly from the curb to get the attention of drivers who are about to run a red light.

On the face of it, the zebra programme is a playful way of making a point about traffic safety. But it's also about changing lives. The programme moves at-risk youth from the shadows into highly public positions of civic authority. The training, structure, support services and social outlet — plus a monthly stipend of 688 bolivianos, or about USD 100 — helps the young men and women stay on track to finish school.

Marco Pachuri, a 24-year-old from La Paz, describes how the weekly work schedule, and support from the programme's small team of psychologists, helped him become more accountable in day-to-day tasks like studying.

Pachuri's mother abandoned his family before he enrolled in high school, and his father used to beat him. After his father's business went bankrupt, Pachuri went job hunting as a teenager, assisting taxi van drivers and delivering crates of Coca-Cola to local businesses. That's when the zebras caught his eye. "I would always see them in the streets, and sometimes they'd stop me," he recalls. "I thought it was beautiful — they'd speak with everyone, kids, the elderly."

Another zebra, Elena Cuevas, says her colleagues double as a surrogate family for her. Cuevas lost her mother when she was just an infant. "They showed me that I wasn't alone, that they loved me," she says. "Everyone is a brother or sister here."

In August, I visited La Paz along with a small group of global city experts to glimpse the inner workings of the zebra strategy, which took home a Guangzhou International Award for Urban Innovation in 2016. The programme's success is in its people. The zebras' enthusiasm is infectious, and imparts a sense of camaraderie and positive influence that can be hard to find in the low-income barrios they call home.

Borrowing from Bogotá

The zebra programme was created in 2001 by municipal officials and artist Katia Salazar to supplement local traffic police. It was inspired by a similar approach in Bogotá, Colombia, during the 1990s — then-Mayor Antanas Mockus sent mimes into the streets to shame drivers and pedestrians whose poor decisions only made traffic worse.

In La Paz, the first iteration of the zebras took a page from Bogotá's punitive mimes. Mascots would blow whistles at drivers who didn't wear seat belts, or pedestrians who stepped into a crosswalk before the walk sign turned on.

"At first, people had a really strong critique of the programme, telling us that instead of investing in this we should be investing in the city," says Sergio Caballeros, who oversees the zebra programme as the secretary of education and culture in La Paz. Caballeros says some people were so incensed by the scolding zebras that they "would try to push them and sometimes cars would try to run them over."

Gradually, the zebras' portfolio expanded. In 2002, heavy rains caused severe flooding that paralyzed the city and killed 60 people. One of the causes was street litter clogging up the drains and sewers. The zebras began encouraging people on the streets to use trash cans, emphasizing that individual actions can make a difference for the greater good. Zebras now also encourage people to avoid eating processed foods and to report any crimes they witness to the police.

"The programme today isn't there to tell people that they have to follow the rules," says Caballeros. "It's to show people that if you want to, you can improve your day, you can improve your life, you can improve the life of your family, if you decide to change your attitude."

Caballeros says the programme has had an impact. While direct results are hard to quantify, the data on traffic accidents in La Paz appear positive. Despite a jump in car ownership in the city, from nearly 130,000 vehicles in 2001 to more than 400,000 today, the number of total traffic accidents is about the same.

A first job

The zebra is now La Paz's unofficial mascot. You can find zebras plastered on billboards and wall murals. Local producers created a TV series based on the zebras. There's even a feature film in the works, although that has stalled due to a lack of funding. "In La Paz," says Mayor Luis Revilla, "there is no football player, no politician, no one that is more popular than the zebra."

For the young women and men in the costumes, the stipend of 688 bolivianos is not enough to live on — the minimum monthly salary in Bolivia is 2,000 bolivianos. But it's enough to supplement their commuting costs. It also helps them pay for college classes, and purchase groceries for their families.

According to Lisett Olivares, a city employee who manages the zebras' day-to-day operations, the programme is designed to act as a "first job" experience for La Paz youth. Zebras dress up for morning and evening rush hour and work a few hours a day, a few days a week. The job gives some participants their first experience with "soft skills" such as showing up to work on time and learning, through conversations on the streets, how to interact with difficult people.

To become a zebra, you have to be enrolled at a local college or high school. On top of the street work, the programme connects zebras with short, internship-like opportunities with the public transit system and local daycare centers, to help round out their work experience. They also help them land real jobs once they've gained enough experience. "We promote 10 of them every year to different jobs within the municipal government," says Olivares.

The programme also offers mental health services, which can be a major boost for work that can put zebras into volatile situations. "It was tough joining the programme at first, because in the first three days, I'd go out to speak with drivers and they'd yell at me," recalls Cuevas, who's studying to become an accountant. Now? "I love what I do."

Zebra spirit

One sunny day, I got a chance to dress up as a zebra, and joined Pachuri and a few others for an afternoon shift. Traffic was jammed on the streets, more so than usual, according to Pachuri; a group of government workers were striking in the city centre and had clogged up avenues near city hall.

As we galloped near the cars, some drivers glared at us. Pachuri was unfazed by it. He told me social interactions on the street, both the positive and negative ones, have made him a more empathetic person today than he's ever been. "You ask some people how their day is," he says, "and they start talking to you for one, maybe more hours."

Zebras are told to greet everyone they encounter, from businessmen to beggars. Many people we talked to seemed grateful for the friendly conversation as a respite from the urban chaos. Others lit up with a smile or laugh when we danced in their direction. A child gave me one of the longest hugs I'd received in years.

Caballeros says the city has conducted numerous surveys to capture public sentiment on the programme. Ninety percent of respondents say they recognize that the zebra programme is educational in nature, and 80 percent say without the zebras, La Paz would embrace the poor driving and pedestrian tactics that kept motor deaths so high. Despite its rough start, the programme thrives today because it's based on "a pedagogy of love," he says.

More than 6,000 youth like Pachuri and Cuevas have passed through the programme since 2001. Since then, it's expanded to additional Bolivian cities like El Alto, Sucre and Tarija. As car ownership grows across Latin America and other parts of the world, it could be a model for other cities to think about. Its impact will be felt for a long time, especially by the young people in the zebra costumes.

"I may not be a zebra forever," says Cuevas. "But I'm always going to carry the zebra spirit with me."

(Travel costs associated with reporting for this story were paid for by the Guangzhou International Award for Urban Innovation.)