Bolivia seeks investors to power up lagging lithium output

December 27, 2017 - Reuters

Alexandra Alper

UYUNI, Bolivia (Reuters) - Bolivia hopes surging global lithium demand can lure foreign investors to the country where nearly a decade of state-led development has left output far short of goals for the metal, coveted by makers of batteries for devices from laptops to electric cars.

Click above picture ßto go to original article to access video in the article.

The poor South American nation boasts nearly a quarter of the world's known resources of the world's lightest metal. Still, production lags far behind neighboring Chile and Argentina. Bolivia hopes to sign a deal with at least one foreign partner to invest up to $750 million in factories to meet rising demand from China and other countries for lithium-ion batteries.

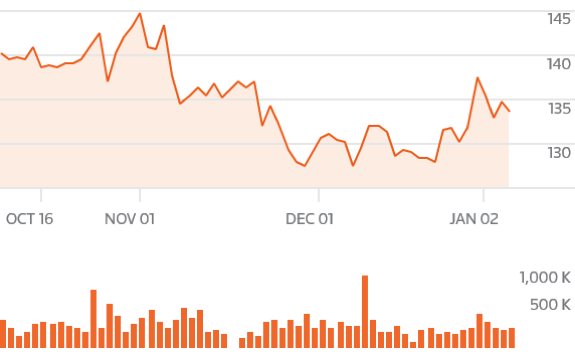

The country is eager to cash in on tightening supplies of lithium. Experts say spot prices have more than doubled to around $25,000 per ton from below $10,000 in 2015.

Rain and other natural challenges, along with execution hiccups, have hampered state-run operations. Foreign companies with more expertise may be spooked by the left-leaning government of President Evo Morales, whose interventionist policies in other sectors have riled some big corporations and made others hesitant to invest, analysts said.

Bolivia had hoped its project at Uyuni, the world's largest salt flat, would produce 40 tonnes per month of lithium carbonate by 2011. Nine years and $450 million into the project, it is producing just 10 tonnes per month.

Elsewhere in South America's Lithium Triangle, Chile produces 70,000 tonnes a year and Argentina 30,000. Total global production is about 230,000 tonnes. Bolivia has sold exports at far below market prices; an employee of state-run lithium company YLB said it was trying to secure market share.

Juan Carlos Montenegro dismissed concerns about slow production.

"That criticism does not hurt us or interest us," he said. "The important thing for us is ... the results we are going to see in 2018 and 2019."

He said Bolivia was talking with potential partners it hopes will invest up to $750 million. He declined to name them but said a deal could be awarded this month for a 49 percent stake in a major expansion that could include up to seven new plants for cathodes, batteries and more.

Next month, bids are due to build an industrial lithium carbonate facility designed by Germany's K-UTEC. That plant, which was slated to produce 30,000 tonnes per year in 2017, is now expected to produce half that in 2019.

However, critics doubt whether foreign industry heavyweights such as Albemarle Corp and Chile's SQM SQMa.SN will risk their capital in Bolivia. Morales has expropriated a series of foreign holdings since taking office in 2006.

Last year, Swiss-based mining and trading firm Glencore Plc said it would begin arbitration against Bolivia over nationalization of some assets.

Foreign companies with the right expertise, including one from Korea, have turned down the opportunity to operate in Bolivia, said Robert Baylis, managing director at Roskill Information Services Ltd, a consultancy.

"They felt either the risk that they would be nationalized or they would face a lot of problems," he said, adding that no one has yet completed a study that shows Bolivian resources could be extracted economically.

To view slideshow, go to original aticle and click on this picture there.

JIGSAW PUZZLE

The lithium market is ripe for new entrants. The niche market for electric vehicles is gearing up for substantial growth as regulators globally tighten limits on greenhouse gas emissions

China, the world's largest auto market, has pledged to make electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles a fifth of auto sales by 2025. Britain and France have pledged to ban sales of combustion engine cars starting in 2040.

Suppliers like Japan's Panasonic Corp (6752.T) and Korea's LG Chem (051910.KS), and U.S. electric car maker Tesla Inc (TSLA.O), which makes its own batteries, are eager to secure long-term lithium supplies.

At Bolivia's Uyuni project, lithium-infused brine lies beneath 10,000 square kilometers of shining white salt, the remains of a vast prehistoric lake on a high Andean plateau that draws thousands of tourists each year.

In a corner of the salt flat, turquoise-colored brine slowly evaporates in rows of vast square pools, leaving behind lithium crystals. These are transferred to a pilot plant and turned into lithium carbonate.

Over a hundred miles east, nestled in the arid mountains that ring the historic silver-mining town of Potosi, another pilot plant in an abandoned Russian tin facility turns the lithium carbonate into cathodes. A third plant next door makes these into simple batteries.

The project was designed to show the Bolivian state could exploit its own lithium, unlike top producers Australia, Chile and Argentina where private firms extract the lion's share of the metal.

Rains often flood the salt flats, lengthening the extraction process. Evaporation, Bolivia's chosen technique, leaves around half the lithium in the brine. Also, the ratio of magnesium to lithium at Uyuni is four times greater than in Chile's Atacama desert, making extraction harder.

Marcelo Castro, leader of the Uyuni efforts from 2007 to 2016, said workers went weeks without washing their hair to conserve water in the project's early days, before water and electricity supplies were set up in the inhospitable landscape. He recalled watching evaporation pools near the salt flat fail, contaminated by dirt carried on the wind.

Castro said he had not planned to spend a decade at the Uyuni project, "but when the needs are urgent you stay."

The project aimed to create an integrated supply chain, helping free Bolivia from overreliance on the whims of volatile commodity markets. Yet the battery plant was built in 2013, four years before the cathode plant. Chinese companies still supply the battery plant with cathodes from abroad.

None of the nearly 3,000 batteries sitting in storage has been sold, according to the plant production manager. Bolivia plans to use at least some of these for rural electrification.

Few outside analysts see a clear path for Bolivia to become a major player in the booming industry.

"It is a puzzle with so many missing pieces. Who can put it together?" said Juan Carlos Zuleta, a Bolivian lithium analyst, who called the project "disastrous." "It's a bad use of our scarce resources."