(above) A Tsimane father and son hunt fish in a river. (Michael Gurven)

These people eat monkeys and piranhas. They also have the lowest rates of heart disease ever measured.

March 17, 2017 - Washington Post

The Tsimane people dwell in thatched huts in a remote corner of Bolivian jungle, and at dinner, the main meal sometimes consists of monkey. Capuchins or howlers. Other days, a hog-nosed coon, or with some luck and a grueling all-day hunt, a man might take a peccary, a kind of wild pig. Some find piranha or catfish in local rivers. For sides, the Tsimane may gather wild fruits and nuts, or harvest small farm plots, where they grow rice, plantains and corn.

Maybe, some will think, all that's their diet secret.

According to a study published Friday in the Lancet, a peer-reviewed British medical journal, the Tsimane have the lowest rates of heart disease ever measured, and in the United States and parts of Europe where heart disease is the leading cause of death, the news is expected to arouse widespread curiosity and a question: How do they do it?

The Tsimane "have the lowest reported levels of coronary artery disease of any population recorded to date," according to the paper written by a team of doctors and anthropologists.

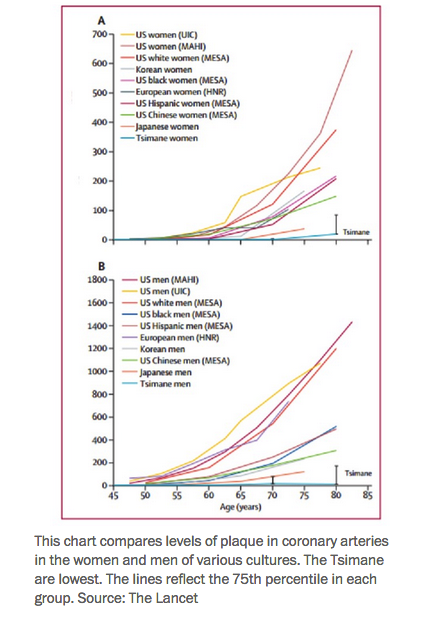

The scientists estimated heart disease during examinations of 705 Tsimane, each of whom traveled about two days by boat and road to get to a clinic. There, they underwent sophisticated X-ray scans of their coronary arteries to determine the amount of calcium plaque, a measure of heart disease. On this basis, the Tsimane measured much healthier than any other people studied, including groups from the United States, Europe, Korea and Japan, according to researchers.

"If you think of the calcium plaque as a reasonable measure of arterial age, their arteries are 28 to 30 years younger than ours," said Randall Thompson, one of the authors and a cardiologist at St. Luke's Mid America Heart Institute in Kansas City. "Obviously the Tsimane are achieving something that we are not."

Previous studies of remote groups have raised doubts about modern lifestyles. For example, a 1984 analysis found that members of the Luo tribe in Kenya who migrated to Nairobi had higher blood pressures than those who remained in the villages. Another, from the '60s, found that the Masai of East Africa had remarkably low levels of blood cholesterol, despite a diet dominated by meat and milk. The Inuit of Greenland also reportedly had low levels of blood cholesterol. And electrocardiograms of !Kung Bushmen led researchers to say their study "confirmed the impression ... that hypertension and ischaemic heart disease, two of the most important heart ailments in Western Society, do not occur in the Bushman."

The studies of the Tsimane began in 1999 when Michael Gurven, a University of California at Santa Barbara anthropologist, first visited, and a few years later, with colleagues, formed a project to study Tsimane lives and health. What distinguishes the Tsimane research is that rather than measure loose predictors of heart risk as the previous research had done, the scientists used computer-enhanced X-ray scans, known as CT, or computed tomography, to gauge how much plaque was clogging the arteries around the heart.

These calcium scores "are the best predictors of heart disease," said Matthew Budoff, a UCLA cardiologist and expert in coronary calcium. "It's a direct measure of atherosclerosis. It's literally measuring the disease in the artery."

The prevalence of heart disease in the United States has inspired a galaxy of research efforts and by most accounts, the causes are manifold: smoking, diabetes, obesity, diet, stress and a lack of exercise are commonly blamed.

The prevalence of heart disease in the United States has inspired a galaxy of research efforts and by most accounts, the causes are manifold: smoking, diabetes, obesity, diet, stress and a lack of exercise are commonly blamed.

For example, a recent analysis of studies of 55,685 people published in the New England Journal of Medicine reported that among people genetically at a higher risk of heart disease, those who had a "favorable lifestyle" — that is, were not obese, did not smoke, exercised at least once a week and ate a sound diet — were about half as likely to experience heart disease.

The relative importance of each of those lifestyle factors is often a matter of fierce debate, however, and the differences over what constitutes a healthy diet is fraught with scientific disagreement and uncertainty. In recent decades, indeed, efforts to quantify a healthy level of dietary salt have metastasized into an epic feud.

"There's a consistency of data throughout the world that people who have low cholesterol, keep active, don't smoke, avoid obesity and maintain their blood pressure live a longer life," said Dennis Bier, a professor at Baylor College of Medicine and editor of the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

But he warned that figuring out how these factors contribute to health is difficult to know.

"People in these other societies often provide us clues to these health questions, but determining the reasons for their unique metabolism is frequently not so easy to do," Bier said.

The researchers likewise acknowledged that the causes of Tsimane health are difficult to distinguish from one another: "Numerous potential explanations exist, and might relate to coronary artery disease risk factors, subsistence lifestyle, genetics" and other factors.

The researchers did note the differences between the Tsimane diet and those of industrialized societies.

By calorie count, about 14 percent of the Tsimane diet is protein, 14 percent is fat and 72 percent is carbohydrate. (By contrast, the typical U.S. adult diets has more fat — about 16 percent protein, 33 percent fat and 51 percent carbohydrate, according to Centers for Disease Control statistics.)

"Importantly," the scientists who studied the Tsimane wrote, their "carbohydrates are high in fiber and very low in saturated fat and simple sugars, which might further explain our study findings."

The Tsimane also exercise — a lot. They use both shotguns and bows and arrows, and their average hunt lasts more than eight hours, covering more than 10 miles of tracking. To cut a farm plot out of the jungle, they generally use metal axes and scythes — not chain saws. And, because of the thinness of the soil, they have to carve out a new plot every growing season.

As a result, less than 10 percent of daylight hours consist of sedentary activity. By contrast, in the industrialized world, more than 54 percent of waking hours are counted as sedentary.

Society, too, may be quite different. The Tsimane live in villages of about 60 to 200 people. They often live relatively long — the most common age at death is 70.

"People often think that life in these places nasty, brutish and short," said Benjamin C. Trumble, one of the anthropologists on the project, who lived among the Tsimane on-and-off for about two years. "But that just isn't the case."

But while the research on the Tsimane and other groups living a "pre-modern" lifestyle suggests that heart disease may be a consequence of modernity, at least some evidence, developed by some of the same researchers, suggests otherwise. Thompson and his colleagues have performed similar scans on 137 mummies from four different ancient populations — in Egypt, Peru, Puebloans from the Southwestern United States and from the Aleutian Islands.

It turns out heart disease may have been common even back then.

"Atherosclerosis was common in four pre-industrial populations including pre-agricultural hunter-gatherers," according to their 2013 paper, also in The Lancet. "Although commonly assumed to be a modern disease, the presence of atherosclerosis in pre-modern human beings raises the possibility of a more basic predisposition to the disease."

There are many reasons, of course, that the Tsimane lifestyle is unlikely to be emulated.

Though they are free of heart disease, they suffer other health problems. They lack clean water and one the most common afflictions is parasitic worms — about two-thirds of adults have them. Their subsistence lifestyle seems to be slipping away, too. Many have begun adding motors to their canoes, bringing the Tsimane into much easier contact with the industrialized world. And finally, the diet is not, at least by some standards, considered tasty.

"Capuchins are more like pork than chicken," Trumble said. "The howler monkeys though, they just don't taste very good. Kind of sour."

Why sitting down may not be as bad for you as you thought

Play Video1:24

An Australian study that found no link between total sitting time and an increased risk of diabetes. (Reuters)