Living alongside Lima's Wall of Shame

May 10, 2017 - Deutsche Welle

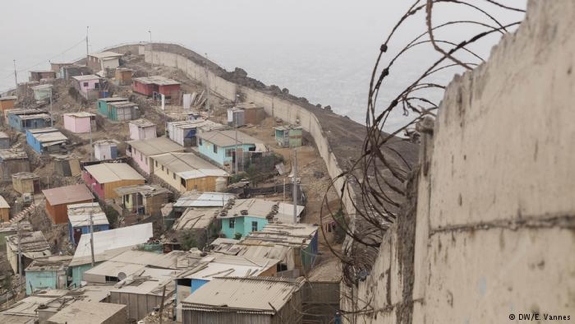

The so-called wall of shame divides two areas in Lima. One belongs to the richest part of town, the other is a slum of wooden shacks, highlighting the Peruvian capital's divide. Jurriaan van Eerten reports.

With a sense of pride, Claudia Luna relates how she and many other migrants managed to stay, even though the police repeatedly came on horses to chase them away. "All these hills were empty when we came," Luna told DW. "Now, bit by bit, we are getting there. Despite the police burning down everything. For us, this is the only way to have a roof above our heads."

What started with a few tents alongside the hill, turned into small houses made of wood and corrugated iron. Concrete stairs were built and electricity wires pulled up. In time, the houses will be rebuilt using bricks, and this new part of the city will eventually be connected to the water system.

This is an example of how Lima has grown as a result of migration from rural areas, which peaked during the war with the terrorist group the Shining Path. Invasions, they are called. People initially illegally claim land. Once they have constructed their houses and are united as a neighborhood, the municipality starts to give them official documents for their land - often to win their vote in the next election cycle.

But in Pamplona Alta the invasion of this pueblo joven (young town) has literally hit a wall: A 10-kilometer (six-mile)-long wall was built by the inhabitants of the affluent neighborhood of Casuarinas on the other side of the hill.

(below) Trying to make ends meet on the wrong side of the divide

Gloria Rosa Avila Cuadras, 52, had lived in the pueblo joven for a year before the wall was extended. She now works as a cleaning lady in a house on the wealthy side for $200 (184 euros) a month. As a result of the wall, it takes her almost two hours to get to work instead of a 15-minute walk down the hill on the other side. Like her, many on this side of the wall work as guards, handymen, plumbers or, nannies.

"We are Peruvian, just like them. So why are they dividing us? We are not all criminals here, like they believe. We are hardworking, but unlucky. So, we call this the wall of shame," she told DW.

Corruption

On the other side of the wall, the price for a square meter can amount to over $2,000. To enter, you must show your identification card to the guards at the gate at the bottom of the hill. Former high-ranking politicians and bank directors live here. Their houses have swimming pools even though water is a scarcity in this area.

Flavio Salvetti, 55, who grew up in Casuarinas, always liked to walk up the hill. He saw how the invasions slowly crept up the other side, claiming all the land, both private and municipal. More recently the squatters have been coming in big organized groups, which makes it even more difficult to chase them away.

According to Salvetti, the wall doesn't keep the criminals out. Gangs have rented houses in Casuarinas to gain easy access to the other houses in the neighborhood.

pic3 (below) Salvetti is convinced that the wall is necessary to stop migrants claiming more land

"Imagine if we didn't have a wall to protect us," he told DW over a coffee in his house, from which he has a stunning view of the city. Asked about the name of the wall, he says: "I think the real shame lies with our past governments. This is the result of decades of corruption. Instead of giving education and possibilities to the poor, they stole the money. The result is that these migrants don't know how to respect property."

Symbolic divisions

Community leader José Sanchez of Pamplona Alta agrees with Salvetti that the root of the problem lies within the state, because there is no distribution of the mineral wealth Peru has.

"We work for minimum salaries on which it is impossible to really survive, while on that side people easily earn 10 times as much," he told DW. "When they need to organize garbage collection or a water system, or build a park, they can pay for it themselves if necessary. We can't when the municipality forgets about us. We live in another world."

Professor Pablo Vega, who teaches architecture at the University La Catolica in Lima, told DW that dividing Lima with walls is nothing new. In the 17th century, a wall was constructed around Lima to keep pirates from entering the port city of Callao. It stood for two centuries. "Walls like these are mostly symbolic," Vega said. "The old wall gave Lima an air of importance."

(below) Authorities have done little to nothing to improve the situation

Asked if he believes Lima will find a solution for the huge socio-economic contrasts that mark the city and the chaotic planning as a result of the invasions, Vega is skeptical. Authorities introduced a 20-year city plan for Lima in 2010 but since then little has materialized in terms of new long-term city planning. According to Vega, this lack of planning and regulation leads to an increased urbanization in high-risk areas such as steep hills and river shores.

"The recent mudslides have shown we really have to do something about this," he said. "Many people had houses in places where they shouldn't have. Now we know where that can lead."