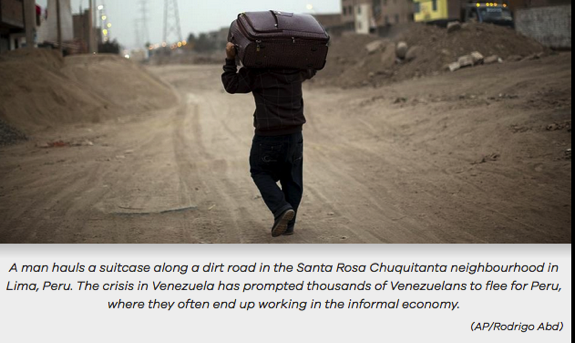

Venezuelan migrants suffer precarious conditions in Peru's informal economy

October 25, 2017 - equaltimes.org

By Jack Guy

Luis Ferrer fled to Peru after his fellow students were killed in anti-government protests in Venezuela. But there he found a different nightmare, typical for migrants, working long, hard hours in a Lima restaurant.

"I had a job doing 12-hour shifts washing dishes, but they didn't only make me do that but also chopping, cooking and waiting tables."

With no contract and terrible working conditions, the 23-year-old Venezuelan left that job after a few days and without pay. "Some jobs don't ask for a permit but the work they make you do is very demanding. It's basically exploitation."

Thousands like Ferrer are employed in businesses ranging from street vendors to restaurants and bars to beauty salons and warehouses, the vast majority working off the books without contracts or labour protection. Unscrupulous bosses also take advantage of recent arrivals who have no idea about how much they should earn, and no legal recourse to demand their rights.

"They recruit people illegally. You aren't on the payroll, you don't have a contract, you don't have anything," said law graduate Bruno Estrada, 23. "As a foreigner you can't work without permission either, so it's illegal, and that's why they exploit you."

Groups of Venezuelans are settling in cities around Peru, and according to activist Paulina Facchin there are between 30,000 and 40,000 in the country in total.

Peru opens its doors

While Venezuelans have settled in various Latin American countries including Colombia, Brazil and Panama, Peru has become a popular destination. There is a strong bond between the two nations thanks to a wave of Peruvian migration to Venezuela in the 1980s.

President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, who has been vocal in his opposition to his Venezuelan counterpart Nicolás Maduro, established a temporary work permit scheme that has already been taken up by thousands of Venezuelans.

While the permit technically allows Venezuelans the opportunity to sign contracts and start businesses, bureaucratic issues mean that, in reality, many are forced into the informal economy. This is a particular problem for recent arrivals waiting for paperwork to be processed; these people are at their most vulnerable in an unfamiliar city.

These precarious conditions put migrants at risk of exploitation, and stories of long hours, poor pay and terrible working conditions are rife.

For many Venezuelans, however, they are better off trying their luck in Peru than struggling to survive at home amid food shortages, lack of medicine and political repression.

Female migrants suffer the additional risk of being subjected to sexual harassment in a country where women face a high risk of gender-based violence which the Council on Hemispheric Affairs has called an "epidemic, embedded in the country's society and culture, which slowly erodes the nation's integrity."

According to hot chocolate seller Massiel Bracho, Venezuelan women in Lima have to adapt to the situation. "The truth is that Peru is more sexist than Venezuela," she said, adding that she is careful to wear modest clothes and walk around with her husband whenever possible.

Improving working conditions and reducing sexual harassment are priorities for the Unión Venezolana en Perú, an NGO set up by migrants to help new arrivals adapt.

Director Garrinzón González, who moved to Lima five years ago, tells Equal Times that the organisation has been working with the Peruvian government on the temporary work permit scheme and other initiatives designed to formalise the migration and labour status of migrants.

Informal jobs crackdown

The efforts of the Union Venezolana come at the same time as a Peruvian government crackdown on informal work, which is a huge problem throughout Latin America. Venezuelan street vendors in one Lima municipality have been encouraged to apply for licenses to formalise their businesses. González encourages migrants to get their papers in order.

However, the next step is to allow Venezuelans to enter the professional workforce in Peru.

According to statistics compiled by the organisation, 60 per cent of Venezuelan migrants in Peru are educated professionals with a university degree. The activists are trying to ensure that these degrees are recognised in Peru, allowing educated migrants to exercise their professions and move away from the informal economy.

Every Friday the organisation puts on a migration consultancy event, helping new arrivals to submit paperwork and ask questions. Outside a packed church hall Luis Rodríguez, 34, sells donuts to peckish attendees.

"There are so many Venezuelans here that are engineers or architects, and they're selling donuts or empanadas," said the business administrator, voicing familiar frustrations. "I don't want to be doing this. I want to work in a company like I was at home."

Despite the difficulties they face, all of the migrants that spoke to Equal Times in Lima said they were grateful for the opportunity to start afresh. González and the NGO appreciate the reception they have been given by the Peruvian government and are working to further improve working conditions for migrants.

At the same time, they are keen to play by the rules of their new home, and avoid any friction with the locals. "At the moment we are in fashion, but there could come a moment when we aren't anymore," he said. "In Panama we are a problem now, and as an organisation we are working to make sure that doesn't happen in Peru."