The Key to Evo Morales' Political Longevity

February 14, 2018 - www.foreignaffairs.com

Why He's Outlasted Other Latin American Left-Wing Leaders

By Santiago Anria and Evelyne Huber

A little more than a decade ago, it looked as though the political left was sweeping Latin America. Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez dominated the regional stage, while left-wing presidents rose to power in a slew of countries, from El Salvador and Honduras to Argentina and Chile. But now there seems to be a turn back in the other direction, as leaders and parties have been defeated in several countries and Venezuela has descended into authoritarianism and chaos verging on state failure.

Yet, one leader survives, and with more stability and success than many initially anticipated. Now, with a recent court ruling removing term limits, that leader is seeking to extend his tenure in office even further. At the current moment, it is worth asking: Why has Bolivian President Evo Morales lasted while other leftist leaders haven't?

THE UNIFIED BOLIVIAN LEFT

Morales was inaugurated as Bolivia's first indigenous president in 2006 and reelected in 2009 and 2014. During his time in office, he and his Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) have transformed Bolivia's political arena and kept a secure hold on power. There has been a notable absence of any significant defections from or challenges to Morales and the MAS from the left, while the opposition has been unable to unite and build an effective coalition.

One key factor behind Morales' success and continued unity on the left is the grass-roots origins of the MAS. Unlike many Latin American political parties, the MAS was shaped from the ground up by a wide array of rural and urban popular movements, which continue to provide a formidable mass base of support. Although the party's genesis predates Morales' rise to power, it consolidated as a national party only once Morales took office. The MAS has performed strongly in every election between 2006 and 2014 and remains the only party with a truly national reach.

A second factor is that Bolivia under the MAS experienced a critical shift in domestic power relations that has empowered large segments of the population that were previously excluded. Subordinate groups linked to the MAS, especially rural indigenous and peasant movements that were previously on the margins of social and political life, obtained a greater say by gaining representation in elected and appointed positions as well as expanded influence over economic and political decision-making. This was an exceptional change in a society characterized by deep ethnic divisions and exclusion, and one that strengthened Morales and the MAS' position in power.

Perhaps most important has been a strong economic performance accompanied by a significant reduction in inequality and an expansion of social welfare policies. Bolivia's energy- and mineral-rich economy has witnessed annual GDP growth averaging five percent since he came to office, reaching a peak of 6.8 percent in 2013. Early on, Morales imposed royalty payments on the extractive industries that generated an extraordinary increase in state revenues and enabled significant public spending on health, education, and social security without creating macroeconomic imbalances. The MAS government has also pushed numerous social policy innovations, including a universal noncontributory pension system and conditional cash transfers to elementary school–aged children to improve access to education. Although these programs are modest in scale, they reach broad segments of society. The Bolivian government has also made remarkable gains in reducing poverty and inequality: since 2006, an estimated one million people have escaped poverty; and between 2006 and 2015, the Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality, declined steadily from 56.7 to 45.5.

Overall, the opposition to Morales has remained weak and divided. In the wake of slowing growth in 2014, the MAS lost a number of mayoral and gubernatorial races, and in 2016, opposition on the left and right temporarily united and captured 51.3 percent of a key referendum vote, just enough to defeat Morales' proposed constitutional change that would have allowed him to legally seek a fourth consecutive term. But this opposition unity was short-lived. And although some social movements that had traditionally supported the MAS had splintered into "loyalist" and "dissident" factions, opposition parties and individual candidates have remained too fragmented and tied to upper classes to pose a serious threat to Morales.

Overall, the opposition to Morales has remained weak and divided.

A SUCCESSFUL SOCIAL PLATFORM

With this staying power and stability, Morales stands in stark contrast to other left-wing leaders in the region. Presidents Chávez and Nicolás Maduro have held on to power by resorting to authoritarianism. In other cases, the left has failed in various ways to keep its voters unified at the polls. The exceptions to this trend have occurred in countries with a political dynamic similar to Bolivia's.

Consider Ecuador and Uruguay, where leftist governments have also managed to stay in power over three consecutive elections. Like the MAS in Bolivia, both the PAIS Alliance in Ecuador and the Broad Front in Uruguay have lacked any significant challenges from the left and have continually faced a weak and divided opposition. Both governments also boast records of strong economic performance and popular social policy reforms.

Ecuador has cash transfer programs similar to those in Bolivia and a noncontributory pension system covering almost as wide a portion of the population as its Bolivian counterpart. Under former President Rafael Correa, the PAIS Alliance government managed to reduce the Gini coefficient in Ecuador from 54.3 in 2007 to 46.5 in 2015, a significant lowering of income inequality.

In Uruguay, too, the Broad Front government greatly expanded noncontributory pensions and family allowances. It also created a single-payer health-care system that goes further than any other in the region in creating equality of access to quality services. And as in Bolivia and Ecuador, the leftist government in Uruguay managed to reduce the Gini coefficient from 47.2 in 2005 to 41.7 in 2015, the lowest in all of Latin America.

Although both countries have seen a decline in economic growth in recent years—Uruguay saw a significant slowdown in 2015 and 2016, while Ecuador's economy stagnated in 2015 and contracted by 1.6 percent of GDP in 2016—each government has, like Bolivia's, remained strongly committed to inclusive social policies and a reduction of inequality. In both countries, however, there are danger signals ahead for the left's continued rule that are not present in Bolivia. In Ecuador, Correa and current President Lenín Moreno became engaged in a bitter feud over corruption allegations and control of the party shortly after Moreno's election, which resulted in Correa breaking away and forming a new party, Revolución Ciudadana, in January 2018. In Uruguay, different factions within the Broad Front are now fighting over possible presidential candidacies for 2019.

HOW LEFT GOVERNMENTS LOSE

Argentina, Brazil, and Chile present three cases where the left lost control of the presidency in recent years. Unlike in Bolivia, the extremely fragmented party system in Brazil never afforded the Workers' Party a secure majority support coalition, and the loss of control of the presidency was the result not of an election but of a highly politicized impeachment process against President Dilma Rousseff tied to an enormous corruption scandal. This process ended in her ouster, allowing leaders of the opposition to seize power.

.

.

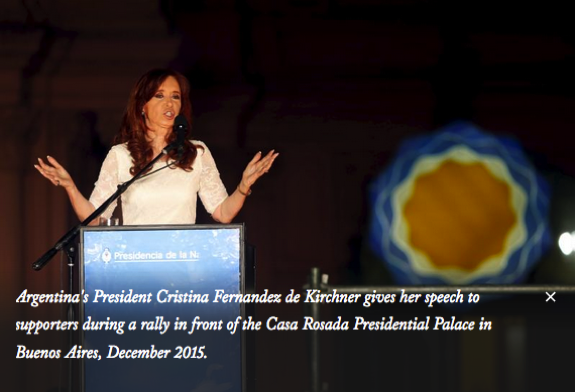

In both Argentina and Chile, splits within the coalition on the left and the construction of a united opposition front—in other words, the exact opposite of the situation in Bolivia—played a crucial role in the left's loss of power in key elections. In Argentina, divisions in former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner's Front for Victory (FPV) party resulted in the 2015 election to the presidency of Mauricio Macri, the right-wing leader of a new party, Republican Proposal (PRO). The 2013 defection of Sergio Massa, a former minister under Kirchner, had already divided the country's Peronists. The disagreement around the candidacy of Daniel Scioli as the FPV nominee in 2015 added further tensions. In contrast, the right formed an effective national coalition, Cambiemos ("Let's Change"), which united the PRO, the Radical Civil Union, and the Civic Coalition ARI. Although Macri placed second in the first-round vote, by uniting the disparate opposition parties, he secured 51.34 percent in the second round, winning the presidency. An economic contraction of 2.5 percent in 2014 and accelerating inflation provide some context for divisions within the FPV and the ability of the opposition to unify.

In Chile also, defections from the left-leaning governing coalition resulted in the left's loss of the presidency in both 2009 and 2017. Consider first the 2009 elections. The Concertación coalition, which was in power up to that point, had always been center-left, going back to its founding in 1988, with the Christian Democrats (PDC) squarely at its center. But with a shift to more progressive policies under Presidents Ricardo Lagos and Michelle Bachelet, tensions within the coalition intensified, leading to the resignation of five PDC deputies in 2008. The Concertación presidential primary in 2009 was widely perceived as rigged in favor of former President Eduardo Frei, which motivated Marco Enríquez-Ominami, a Socialist deputy, to launch his candidacy as an independent. He received 20 percent of the vote in the first round of the elections. In contrast, the right had united behind Sebastián Piñera early on, and he was able to attract 51.6 percent of the vote in the second round of the election, thus winning the presidency.

When the left won back the Chilean presidency in the 2013 elections, the tables turned. There was significant wrangling through a complicated primary process on the right, whereas the left widened its coalition to include the Communist Party and united behind Bachelet, who had left the presidency in 2010 with very high approval ratings. The election results were the strongest for the left since the country's transition to democracy, with 62 percent voting for Bachelet and two seat gains in the senate and ten in the lower chamber.

When the left lost the Chilean presidency once again in 2017, it was with even greater divisions than had been present in 2009, again in stark contrast to the unity of the Bolivian left under Morales. The member parties of the Nueva Mayoría ("New Majority"), the leftist coalition that had replaced Concertación in 2013, gradually united behind one candidate, Alejandro Guillier, but the Christian Democrats broke with the coalition altogether and nominated their own candidate. In addition, Enríquez-Ominami once again ran as an independent, and Beatriz Sánchez, the presidential candidate for a newly created leftist coalition made up of various social movements called the Frente Amplio ("Broad Front"), managed to attract wide support. The result was that the center-left vote in the first round was split among four candidates. On the right, Piñera won the primary easily and faced only one minor competitor from the right in the first round. The first-round results gave 48.7 percent of the vote to the three candidates from the left and 44.5 percent to the two from the right, with the Christian Democratic candidate getting 5.8 percent. Although this hardly marked a shift away from the left in the electorate, the right was ultimately more successful in mobilizing and uniting its supporters in the second round, yielding a victory for Piñera.

Chile's moderate but steady economic growth can hardly account for the growing fissures in the center-left. Yet despite major initiatives in social policy under Lagos (health care extending guarantees for free or subsidized treatment for a specified number of illnesses) and in Bachelet's first term (vastly expanding and modifying a noncontributory pension system) and a dramatic reduction in poverty, there has been virtually no change in the high levels of inequality since 2005, in sharp contrast to what Bolivia has experienced. It was arguably disappointment over the limited progress made on Bachelet's ambitious reform agenda that led to the challenges from the left.

WHAT THE FUTURE HOLDS

In short, Morales has been able to stay in power thanks to continued strong economic performance and significant progress in redistributing income and power. This has so far prevented the emergence of significant electoral challenges from the left or the opposition. Similar trends account for the longevity in office of left-wing parties in Ecuador and Uruguay, whereas the opposite dynamic has been responsible for the defeat of the left in Argentina and Chile.

Moreover, it looks as though Morales is set to continue his tenure in office. Lacking a viable successor, the MAS responded to the 2016 referendum loss prohibiting Morales from seeking another term by petitioning the country's Plurinational Constitutional Tribunal to remove the term limits and obtaining a favorable court ruling. Despite this legally questionable maneuver, however, Morales' chances of winning reelection once again remain high given his continued popularity.