Landmark case in Florida pits Bolivia's ex-leader against villagers attacked by his army

March 6, 2018 - Miami Herald

By David Ovalle dovalle@miamiherald.com

On a rocky and impoverished rural slice of Bolivia, the noise sounded like corn popping loudly.

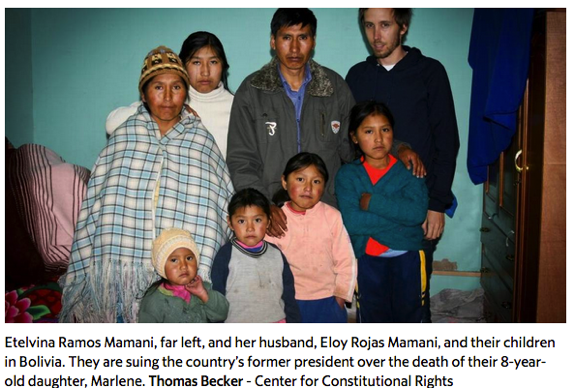

Etelvina Ramos Mamani was lying on her bed, weak and feverish. She heard a scream from next to the window. Her 8-year-old daughter, Marlene, suddenly collapsed and tilted her head back, desperately trying to suck air into her lungs — pierced by a bullet fired by Bolivian soldiers.

"Blood was coming out of her chest like a fountain," Ramos testified Tuesday.

Outside, the government soldiers were charging through the small village, firing away. Hours passed before the shooting stopped. By then, as her relatives held an impromptu wake in the dark, Marlene was dead — an innocent victim of the violent unrest that wracked Bolivia in the fall of 2003.

Ramos took the witness stand Tuesday not in South America, but 3,000 miles away in a Fort Lauderdale federal courtroom.

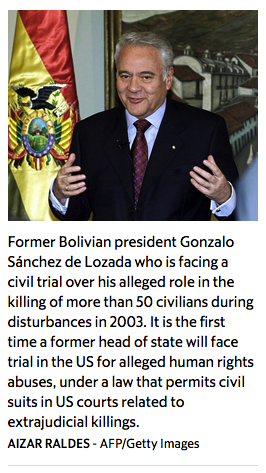

Her testimony marked the start of a landmark court battle that pits relatives of the poor, mostly indigenous people killed in the chaos against Bolivia's ex-president Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, and his former defense minister, José Carlos Sánchez Berzain.

Tuesday's testimony marked the first time that a former head of state of a foreign country faced trial in a U.S. civil court for human rights abuses, according to the Center for Constitutional Rights, which is representing the Mamani family.

Tuesday's testimony marked the first time that a former head of state of a foreign country faced trial in a U.S. civil court for human rights abuses, according to the Center for Constitutional Rights, which is representing the Mamani family.

"My daughter was innocent. She had not even gone out. She was playing inside the house," said Ramos, who sported two long braids, a pink sweater and a turquoise skirt typical to the indigenous people of her region.

Her husband, Eloy Ramos Mamani, recalled soldiers chasing and firing on unarmed villagers. "Like scared rabbits they escaped to the hills," he told jurors.

The couple belongs to one of eight families suing the former Bolivian government leaders under the U.S. Torture Victim Protection Act, which allows suits for extrajudicial killings in foreign lands. The suit was filed in South Florida, where the two former politicians now live after fleeing Bolivia in 2003.

The legal wrangling over the case has lasted for nearly a decade, and the trial is expected to last several weeks before U.S. Judge James Cohn. The relatives of the slain Bolivians are represented by lawyers from the Center for Constitutional Rights, Harvard Law School's International Human Rights Clinic and several high-powered private law firms.

The couple's story was one powerful vignette of a larger geopolitical conflict that is still playing out in the landlocked South American country.

In 2003, civil unrest was tearing apart Bolivia after Sánchez de Lozada proposed exporting the country's natural gas to the United States. Protesters, many of them indigenous Aymara people, began blocking roads, marching on the presidential palace in La Paz and demanding his resignation. The president's opponents believed exporting gas was another in a long-running exploitation of Bolivian indigenous people's lands, enriching the elites while leaving everyone else mired in poverty.

This wasn't the first time Bolivia's poorest citizens had rejected the government's appropriation of natural resources. In the late 1990s, in the so-called "Water War," massive protests forced Bolivia to abandon plans to privatize a water system in the city of Cochabamba.

During the violent clashes of 2003, more than 50 people were killed. The unrest was headed by Felipe Quispe Huanca, an Aymara leader known as the "Condor," and Evo Morales, who went on to become Bolivia's controversial leftist president, a position he still holds.

The defense strategy will be to point the finger at the politically powerful protest leaders who, they argue, incited violent street uprisings. A federal jury will be tasked with deciding who, if anyone, is at fault and what, if any, money to award the relatives of the dead.

"The men responsible for that tragedy are not in the courthouse today," said Anna Reyes, representing former president Sánchez de Lozada.

But lawyers for the Bolivian families painted Sánchez de Lozada and his ministers as callous and intimately involved in the military's use of force to quell largely peaceful protests.

During opening statements, jurors saw photos of the eight dead, as well as detailed maps showing where military incursions took place on separate dates in towns across Bolivia.

Heavily armed soldiers fired "indiscriminately" at townsfolk, the plaintiffs' lawyers. Among the victims: A pregnant wife was killed after a bullet was fired through the wall of a house, killing her and her unborn child; a 69-year-old father was gunned down alongside a road; and a teenager was shot when she went to a rooftop to try and glimpse the action.

"While neither of the defendants pulled the trigger, they are responsible," said attorney Joseph Sorkin, adding: "You can't unleash the military to shoot at unarmed civilians."

At the mountain town of Sorata, roadblocks stranded hundreds of tourists and visitors attending a religious festival. Berzain, according to lawyers for the families, was sent to broker a deal that ended in him threatening to shoot you "f---king Indians" and the launch of a deadly military convoy.

But lawyers for the former president put the blame squarely on Quispe and Morales for pushing violence that they argue paralyzed the nation, leaving La Paz shut down and struggling to provide food and fuel to citizens. Morales, a former coca farmer and the labor leader, was angry with the administration's crackdown on the cultivation of the plants used for the production of cocaine, Reyes said.

Reyes said the two repeatedly rejected concessions by Sánchez de Lozada, who was first elected in 1993 and — after a term out of office — again in 2003.

The former president's legal team painted him as a genuine free-market reformer who helped pull Bolivia from economic woes, only to be backed into a corner by opposition that regularly employed gunfire and dynamite against police and soldiers.

His order to the military to help quell the violence was lawful, and by the time it was actually enacted, all of the plaintiffs' relatives had already been killed, they said. In one case, the pregnant woman was killed by a bullet that came from a rooftop shooter — not a soldier, but from a protester, Reyes said.

Prosecutors in Bolivia have deemed the military's response to the protests as "proportional," she said. After Sánchez de Lozada fled to South Florida, he even asked the United Nations' Human Rights Commission to investigate the killings.

"The U.N. didn't do that investigation," Reyes told jurors. "But we have something even better. A U.S. jury."