A Surprise Win for the Victims of Bolivia's Gas War

April 6, 2018 - NACLA

This week, a jury found Bolivia's former president, Gonzalo "Goni" Sánchez de Lozada and his Minister of Defense guilty of extrajudicial killings in 2003 in a landmark case. For their victims, it's a welcome victory.

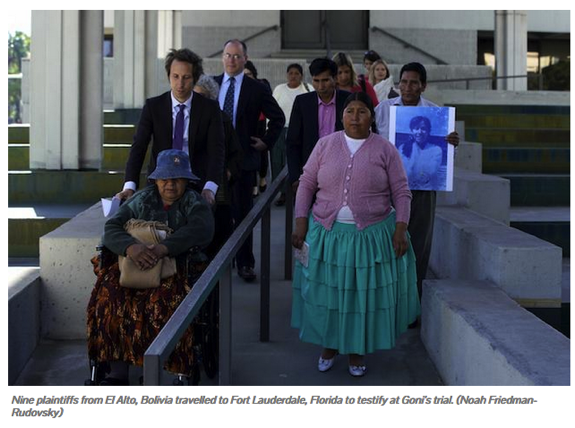

On Tuesday, a jury in a U.S. federal court in Fort Lauderdale, Florida decided that Bolivia's former President Gonzalo "Goni" Sánchez de Lozada and his Minister of Defense Carlos Sánchez Berzaín are legally responsible for extrajudicial killings. Their conviction, which sets legal precedent, falls under the concept of command responsibility—which holds commanders and other leaders answerable for crimes committed by their subordinates. The nine plaintiffs in the civil case, whose families died amid protests over a proposed natural gas pipeline in 2003, were awarded $10 million by the court.

The trial concerned the Bolivian government's bloody response to crippling road blockades that cut off food and gas deliveries to La Paz in September and October 2003, when Goni and his cabinet declared a state of emergency and deployed the military to restore control over the largely Indigenous highland city of El Alto. A massacre resulted: the military was ill-equipped to manage the urban protest, and by its end, the conflict had left 60 people dead and almost 400 wounded, almost all the victims from low-income indigenous Aymara communities.

As deaths associated with the military mounted, a steady stream of Bolivian politicians, including Goni's former Vice President, Carlos Mesa, condemned the killings and resigned from office. Goni and Sánchez Berzaín fled to the United States, claiming political persecution, and have lived in Maryland and Florida, respectively, ever since. The U.S. government granted Sánchez Berzaín political asylum in 2008, legitimating the men's claim of persecution.

Fifteen years later, I accompanied one of the plaintiffs to Fort Lauderdale to testify in U.S. federal court. Juana Valencia de Carvajal, or Doña Juana as everyone calls her, is in her late 60s, dressed in typical Aymara women's clothing of a wide skirt (pollera) and bowler hat. On the long plane ride north from El Alto, she told me that at the age of eight, her parents took her from her tiny highland village of Likinos to work as a maid in La Paz. She had no opportunity to go to school. Ten years later, she married Marcelino Carvajal, who she knew from her village. Marcelino found work in a soap factory in central La Paz and they had 12 children together. Only six survived until adulthood.

In 2003, at the height of the El Alto uprising, a stray military bullet shot and killed Marcelino at home when he was closing a window. After his death, Juana struggled both emotionally and financially. She went back to work for the municipality as a gardener, but, as she was already in her mid-50s, it didn't last long. "We've been waiting for this for fifteen years," she said about the trial. "We want to tell Goni and Sánchez Berzaín exactly what they did to us and to our families."

The lawyers representing the case selected the nine plaintiffs with the strongest evidence. If and when the compensation finally comes through, they plan is to share it. Juan Patricio Quispe, who lost a brother in the conflict, is the President of the Victims Association, which worked closely with the legal team bringing the case to the trial in the U.S. He explained that "we all signed an agreement to divide any reparations equally between those whose family members died and the four of our group who lost limbs."

As Doña Juana and the other plaintiffs waited anxiously, the jury deliberated for a full six days before they returned a guilty verdict. The 10-person jury—standard in civil cases—was mostly older and about half African American, with two Latinxs. During the selection process, the defense asked if any of the potential jurors had ever attended a protest—none of the selected jurors had. Yet the trial outcome clearly demonstrates that the jury empathized with what people in a very different part of the world had suffered at the hands of their government.

A consortium of U.S. human rights lawyers brought the landmark case to court under the 1992 Torture Victims Protection Act, one of the world's most comprehensive human rights provisions. It allows civil suits within the U.S. to take place in the case of extrajudicial killings and torture carried out by foreign government representatives, once redress in victims' country of origin are concluded. The case signified the first time that an ex-President had to respond before the U.S. courts for human rights abuses. "The United States should not be a safe haven for human rights abusers," said Beth Stephens, an attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights, one of litigants for the plaintiffs.

A consortium of U.S. human rights lawyers brought the landmark case to court under the 1992 Torture Victims Protection Act, one of the world's most comprehensive human rights provisions. It allows civil suits within the U.S. to take place in the case of extrajudicial killings and torture carried out by foreign government representatives, once redress in victims' country of origin are concluded. The case signified the first time that an ex-President had to respond before the U.S. courts for human rights abuses. "The United States should not be a safe haven for human rights abusers," said Beth Stephens, an attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights, one of litigants for the plaintiffs.

The trial lasted three weeks and hinged on who bore responsibility for the injuries and killings. Goni and Sánchez Berzain's defense team argued that the deaths resulted from armed confrontation between the military and armed protestors, which they claimed were led by current Bolivian President Evo Morales and Felipe Quispe, an Aymara leader. In a 2007 interview, former U.S. Ambassador to Bolivia, David Greenlee, contended the 2003 killings were the result of "military indiscipline." Defense attorney Ana Reyes insisted to the court that "there was no plan to kill people," during the first week of the trial. She continuously characterized Morales and Quispe as inciting violence and refusing to negotiate with Goni's government—even though Morales was out of the country at the height of the conflict.

The plaintiffs' lawyers, led by Joseph Sorkin, responded that as only two or three police died compared to 60 civilians, the theory of an armed confrontation was untenable. Construction laborer Luis Castellano Romero, who had his leg shot off when he was on his way to tell his father to come home for lunch, told the court in a deposition filmed in Ecuador that he had never seen any protestors with guns.

When Goni took his turn on the stand, he insisted that he had tried everything possible to establish a dialogue with the protestors and never ordered the military to shoot. His Defense Minister, Carlos Sánchez Berzain, widely viewed in Bolivia as pressuring Goni to opt for repression over negotiation, testified that he held no liability for the deaths because he only had an "administrative role" in the government. Instead, he blamed Evo Morales, accusing him of plotting to assassinate Goni.

Among the witnesses testifying against Goni and Sánchez Berzaín were his former Vice-President and two of his government's ministers. José Luis Harb, who was Vice Minister of Internal Security and the Police in 2003, testified that "As the person responsible for the country's internal security, I had access to police intelligence reports. I never received a single one about armed subversive groups."

La Paz's mayor in 2003, Juan del Granado, took the stand for three hours. He said that during the conflict, he spoke with members of Goni's cabinet, who informed him the cabinet was deeply divided. One side urged dialogue, while the other, headed by Sánchez Berzain, argued in favor of repressing the uprising. Del Granado further testified that Goni had rejected his efforts to organize a dialogue in September 2003.

Bringing Goni to Justice

It took ten years of dogged work by a consortium of U.S. human rights lawyers to get the case to court, much less find the two former officials guilty. In May 2014, U.S. Federal Judge James Cohn ruled that the plaintiffs' claims could advance because they indicated that the killings could have been deliberate. Then, in June 2016, a U.S. appeals court rejected the defense claim that the court should drop the case on the basis of a small amount of indemnization that the plaintiffs had received from the Bolivian government. The decision sets legal precedent as the first time a U.S. federal appellate court had addressed an argument by defendants concerning the termination of legal options in another country.

Much of the lawyers' success came down to the tenacity of Tom Becker, who was a young Harvard law student when he arrived in Bolivia in 2005. While working as intern with the Bolivian lawyer Rogelio Mayta, who has worked indefatigably with the victims for over ten years, Becker succeeded in interesting Harvard's International Human Rights Law Clinic in participating in the case. "This is about justice, about poor Indigenous peasants denouncing the richest and most powerful man in their country," Becker said after the verdict. The legal team grew to include attorneys from the U.S. law firm Akin, Gump, Strauss, Haver and Feld.

Much of the lawyers' success came down to the tenacity of Tom Becker, who was a young Harvard law student when he arrived in Bolivia in 2005. While working as intern with the Bolivian lawyer Rogelio Mayta, who has worked indefatigably with the victims for over ten years, Becker succeeded in interesting Harvard's International Human Rights Law Clinic in participating in the case. "This is about justice, about poor Indigenous peasants denouncing the richest and most powerful man in their country," Becker said after the verdict. The legal team grew to include attorneys from the U.S. law firm Akin, Gump, Strauss, Haver and Feld.

Parallel to a civil case in the US, for over ten years, the Bolivian government has attempted to extradite Goni and Sánchez Berzaín from the United States to face trial in Bolivia. The U.S. rejected the first case in 2012, allegedly because the charges it detailed lacked equivalency in U.S. law; the second attempt submitted in February 2016 is languishing in Washington without a response to date. Although the civil case in Florida has no connection to the extradition petition in Washington, Bolivian government officials believe that the verdict strengthens their arguments for extradition.

"The Bolivian government hasn't been capable in all these years of accomplishing what a brave group of citizens have achieved," wrote former government minister, Rafael Puente, in Página Siete, a local paper. Despite the failure to date to achieve extradiction, in 2011 the Bolivian Supreme Court handed down a guilty verdict in a multi-year trial against five military commanders and two government Ministers who participated in the massacre and who were still in the country. Goni and Sánchez Berzaín could not be tried because they were out of the country.

Goni and Sánchez Berzain's lawyers are already planning their appeal. In a statement, Stephen Raber and Ana Reyes of the Washington-based legal firm Williams & Connolly wrote, "We don't agree with the jury's decision and we believe that the evidence was so scarce that the case should never have gotten to a jury. We believe that the verdict will be overturned once the law is applied correctly." They added that the events of 2003 were tragic for all Bolivians, "including our clients.

Their lawyers submitted a defense motion to the judge in the case, under Rule 50, which argues that the plaintiffs presented insufficient evidence to support a verdict in their favor. A decision is expected May 4. Despite the anxiety this has generated among the families, Washington-based civil litigation expert Steven Sprenger explains, "I can't think of a single case I have tried where the defendant didn't make a Rule 50 motion at every possible stage of trial. The judge's comments indicate he is troubled with the sufficiency of plaintiffs' evidence, but that doesn't mean he'll take away the jury verdict."

Meanwhile, the plaintiffs and their supporters are celebrating what for so long seemed like an impossible dream. The family members of the victims publicly expressed gratitude to the jury. "I want the entire world to know that this tragedy was so immense that not even their lawyers could cover it up," said Teófilo Baltazar, who lost his wife and unborn child in the massacre.

Photojournalist Noah Friedman-Rudovsky worked in Bolivia during 2003 and its aftermath. "Thirteen years ago, I traipsed around El Alto with lawyers on what I was sure was a fools' errand," he remembers, "reenacting the scenes where people were shot—a child in her mom's bedroom, a pregnant woman in her living room, a woman running away from helicopters shooting indiscriminately. But never underestimate the Alteños; they and an amazing crew of lawyers pulled off the longest of shots."

The victims' lawyer, Rogelio Mayta, attended most of the trial. "We celebrate the court's decision, but we do it aware that this is just one chapter in a very long history," he said. "In the end, the truth triumphed and Goni and Sánchez Berzaín have been revealed as nothing more than violators of human rights."

Linda Farthing is a writer based in Bolivia. She is author of three books on Bolivia and serves as a contributing editor to NACLA.