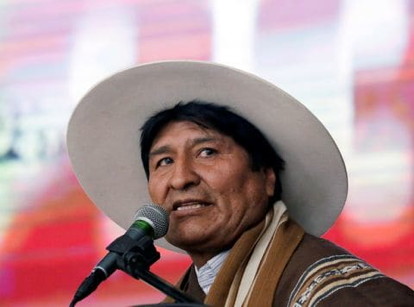

(above) President Evo Morales of Bolivia is preparing to run for an unprecedented fourth term. (David Mercado/Reuters)

The cynicism of Evo Morales’s reelection bid in Bolivia

January 4, 2019 - Washington Post

by Francisco Toro

Not much remains of the pink wave — the tide of left-wing governments that swept Latin America at the turn of the century. One way or another, country after country has turned back either to the center (Peru, Ecuador), the right (Argentina, Chile) or even the far right (Brazil).

As alternation in power between opposing ideologies becomes normal in Latin America for the first time, just a handful of stragglers hang on: Nicaragua and Venezuela, where leftist authoritarianism has done away with democracy altogether, and Bolivia, where democracy is genuinely on a knife-edge.

Bolivia has always been a special case. Uniquely for the Latin American hard-left, its government managed public finances with relative prudence. While socialists in Venezuela and Nicaragua lay waste to people’s standards of living, the government of President Evo Morales has overseen more than a decade of economic stability and real poverty alleviation. But it has also hitched economic competence with the standard leftist suite of authoritarian measures: packing courts with cronies, ignoring checks and balances, presiding over pervasive, unabashed corruption, etc.

Keep Reading

Now, ignoring the will of the people expressed in the ballot box, Morales is trying to hang on to power indefinitely, creating an existential threat to what’s left of Bolivian democracy.

To grasp how, you have to understand the role that term limits play in Latin America. In a region where the presidency has always been the overwhelmingly dominant political institution, the benefits of incumbency are supercharged. With courts seldom able to provide a real check on presidential power, it’s rarely possible to compete fairly with an incumbent seeking reelection. Able to mobilize state resources, media and employees in support of their reelection bids, incumbents have overwhelming advantages. That’s why term limits have proved necessary to allow real electoral competition in the region. Without them, incumbents have little trouble steamrolling their opponents.

The people of Bolivia, it turns out, agree with that. In 2016, Morales called a referendum to amend the constitution he himself had championed so that he could run once more.

But Bolivia said no. A 51.3 percent majority voted against Morales’s bid for an unprecedented fourth term, a move that would almost certainly have cemented his indefinite hold on power.

Undeterred, Morales turned to the Constitutional Tribunal — whose judges he personally appointed — to change the results of a referendum he had personally called. Alleging that standing for election is a fundamental human right, he had his judges declare the referendum void, overruling the 2,682,517 Bolivians who had just voted to keep their constitution’s term limits in place.

It’s hard to overstate the cynicism of Morales’s argument. He cited provisions of the inter-American charter designed to prevent authoritarian governments from picking who can challenge them and jujitsued them into an argument against term limits. In one especially egregious passage, Morales cited Inter-American Court of Human Rights rulings in favor of Leopoldo López, the high-profile Venezuelan political prisoner, in support for his bid to become a Venezuelan-style dictator. It was stomach-churning.

Surprising no one, his supine court sided with him. If his previous reelection campaigns are any indication, Morales will spare no effort to mobilize state resources in support of his bid, giving him an enormous unfair advantage that could overcome his growing unpopularity at home. Bolivia’s democracy could take years to recover.

Now the case is going up to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in Costa Rica, where a panel of international judges will be asked to scrutinize the Bolivian Constitutional Court’s nonsense ruling.

For Jorge Quiroga, the former center-right president of Bolivia who is leading the opposition to the move, the real question is whether the Inter-American Court system will act “like a fancy, modern hospital that performs only autopsies on dead democracies, or like a real hospital that intervenes early enough to save the patient.”

Quiroga noted during an interview that in the Venezuelan and Nicaraguan cases, the Inter-American Court did indeed pass strong decisions rebuking governments for anti-democratic excesses, but it did so far too late, after local institutions had already been decimated.

Ultimately, the remaining pink wave governments have stayed in power only by turning decisively away from democracy and strengthening their alliances with one another, and with Cuba, the original springhead of the Latin American far left. Venezuela, Nicaragua, Bolivia and Cuba increasingly depend on one another for diplomatic cover, intelligence support and mutual recognition.

As Quiroga puts it, Latin America will end up either with four Cubas or with none. The Inter-American Court in San José now has a unique opportunity to help decide which it will be.

______________________________________

Read more:

Francisco Toro: China exports its high-tech authoritarianism to Venezuela. It must be stopped.

Francisco Toro: No, Venezuela doesn’t prove anything about socialism

Dánae Vílchez: Ortega continues to suffocate protests and the press in Nicaragua

The Post’s View: Nicaraguans are waking up to the political rot in their government