February 8, 2019 - CondeNast Traveler

LA PAZ IS NOW BURSTING WITH DESIGN HOTELS AND EDGY RESTAURANTS THAT BREAK ALL THE RULES.

By CHRIS MOSS

I can't seem to get my gait right. I’m on the Prado, the main avenue in downtown La Paz. The slope is behind me, so I can just about breathe. The problem is, paceños speed up when they are walking downhill. Yes, those approaching me have an elegant, 19th-century pace. They link arms, take their time. But those jostling beside me are moving much faster, zigzagging through the crowds, phones clamped to ears, shouting out deals and private dramas as if there were oxygen in the air.

In La Paz, 11,811 feet above sea level, breathlessness is part of everyday life. As is hustle, bustle, the raw human energy of almost a million people living in a caldera-shaped canyon. Sometimes I feel as if we’re all tumbling down toward a putative center—but I can’t see one. The plazas are thronging with pedestrians and cholas—bowler-hatted Aymara women—seated at their stalls selling salty, greasy snacks, glasses of mocochinchi made with dried peaches and cinnamon, souvenir llama-motif bobble hats, and SIM cards. The roads are packed with battered cabs and Dodge buses painted in vibrant colors. Respite is a rare commodity.

(below) A flower market. Julien Capmeil

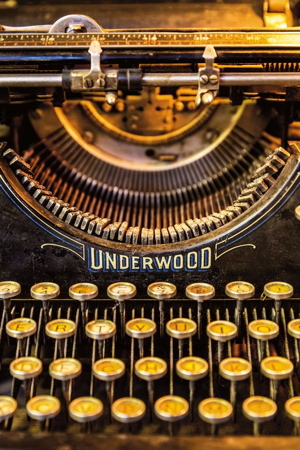

(below) The Writer's Coffee. Julien Capmeil

Fortunately, Boris Alarcón, a bright Bolivian entrepreneur, has opened a trio of cafés under the Hierro Brothers brand in the heart of town. The Writer’s Coffee, in the old Gisbert bookshop on Calle Comercio, is dimly lit and beautiful, with Adler, Triumph, and Torpedo typewriters on display, and tall shelves crammed with sober-looking academic reference books. A couple of blocks away, KM-0—which opened last June—is the most elegant of the three, housed on the upper floor of an early-20th-century mansion and offering the city its first hip co-working space. And the HB Bronze Coffeebar is a popular afterwork meeting space in Alarcón’s biggest venture, the palatial Altu Qala hotel, opening in April.

“This will be the coolest and most upscale hotel in Bolivia,” says Alarcón, who lives between La Paz and Berlin. Altu Qala is certain to be a unique small hotel: Alarcón’s cafés are as trendy as any in London or Copenhagen. His baristas wear tight T-shirts and trilbies, and turn out 34 different kinds of coffee, including slow-macerated Japanese brews. But I’m not here for hipster coffee. I’m here for psychogeography, and my fellow cortado sipper is an expert. Carlos Mesa, who was Bolivia’s president from 2003 to 2005, is also one of its foremost writers. I ask him what it means to live in the world’s highest capital city.

“La Paz and the mountains are inseparable,” he says. “We’re in the shadow of Illimani, one of the most beautiful mountains in the world—and when we are away we think only of that. Indigenous culture is not something from the past. People still believe the mountains are apus, or protective spirits.”

(below) Sculptures. Julien Capmeil

I remark that, for me, even more striking than the dramatic mountain setting is the way La Paz feels enclosed, like a huge bowl. “Yes, and because of that we are frightened of empty, wide-open spaces,” he says. “A paceño out on the plains feels terror.”

Mesa is no fan of Evo Morales, South America’s first indigenous president, who took his seat in 2006. He calls him a pure capitalist and a shameful self-mythologizer. But despite being a political opponent (he challenged him again in January’s elections), Mesa acknowledges that Evo, as he is often called, has been good for La Paz. “When Evo came to power, he was quick to reassert La Paz’s status as capital. This, and the pro-indigenous politics, has united the city and given it new confidence.”

After recent visits to all the big cities on this continent, I’d say La Paz is changing faster than any other. Its renaissance comes after decades of sleepy stagnation. In Zona Sur (the south side), a residential and commercial district that is lower and a few degrees warmer than the historic center, the city’s first smart boutique hotel, Atix, opened in 2016, its interiors built from native wood and Comanche stone, its walls hung with works by Bolivia’s best-known artist, Gastón Ugalde. The striking parallelogram- shaped tower is the result of a collaboration with New York design studio Narofsky Architecture. “Our aim is to share our cultural wealth with the rest of the world,” says owner Mariel Salinas. The cool cocktails made from singani and other native firewaters served in the bar, +591 (Bolivia’s phone code), were created by David Romero, a former mixologist at Lima’s award-winning Central Restaurante; and Ona restaurant serves sublime Andean food.

(below) Hats at Gustu. Julien Capmeil

(below) Edible flowers at Gustu. Julien Capmeil

That said, the competition in the barrio is fierce. Around the corner is Gustu, a restaurant opened by Claus Meyer, cofounder of Copenhagen’s celebrated Noma restaurant and the man credited with setting off the Scandi food revolution a decade ago. “He was looking for a country with amazing produce but no real cuisine,” says Surnaya Prado of Gustu. “He had made a short list of four, but he came to Bolivia first, and his journey ended here.” The lofty dining space, decorated in bright textiles, masks, and recycled vintage furniture, looks almost as gorgeous as the food served by chefs Mauricio López and Marsia Taha and their youthful team. Lunch is a seven-course sampler, including llama tartare, Amazonian sorubim fish with bananas and chili, and a sorbet of tumbo fruit with gin. Denmark suddenly seems a bit last century.

At the neighborhood’s most stylish homegrown shop, Walisuma, partner Patricia Rodríguez shows me $1,000 vicuña wool scarves, baby-soft llama-hide bags, kitchenware made from recycled Bolivian rosewood, and floaty dresses in muted colors that feel ethnic but avoid the crude iconography of tourist garb. “We use coca leaves, plants, and herbs in our natural dyes,” Rodríguez says. “We have modernized the motifs so the fabrics denote the region but are fashionable. That’s what our clients want.”

Zona Sur has cute coffee shops, Asian fusion restaurants, private art galleries, and flagships of Italian luxury brands. But it also has a proper food market, where everyone seems to be chin-wagging as they pick up tropical fruit, high-plains vegetables, quinoa, and other now-cool superfoods such as maca and vitamin C–rich camu-camu. It also has a very good old-school pie shop, Salteñas Potosinas. The tasty snack is laced with chili. A group of local food historians have started a campaign to prove chilies originally came from upland Bolivia. It’s time, they say, to reclaim their gastronomic gift to the world.

(below) A traditional shawl. Julien Capmeil

(below) Woven blankets. Julien Capmeil

I take a cable car to the hilltop suburb of Sopocachi. The new network of aerial public transport has been opening in stages since May 2014. Eight lines currently operate, with three more under construction. The Austrian-built system has halved the commute for suburbanites. It gives me a chance to see the city beyond Zona Sur.

While chatting with a friendly fellow passenger, I look down over schoolyards full of children in red uniforms; homes with pools, gardens, and pedigree dogs; soccer fields; an Olympic swimming pool; a church for every parish; office blocks; and residential towers built in orange brick, their flat roofs a jumble of cables and antennae. Cars, cabs, and buses race along winding ribbons of expressway. Every narrow sidewalk is filled with walkers, workers, students, all dashing around. Again, I have that impression that life in La Paz is centripetal, arrowing inward but with nowhere to come to rest.

Sopocachi is a liminal zone—falling between the business-minded south and old center. It looks faintly European and is as close as La Paz gets to laid-back. A few minutes’ walk from the cable-car station is a staircase up to the Montículo, a neat little park with cypress trees, a marble fountain of Neptune, and a walled-in viewpoint. A cobbled street leads away from here. I meander without a plan. If I get lost, I’ll look for the peak of Illimani and reset my compass.

(below) Bolivian artist Gastón Ugalde, with his work. Julien Capmeil

Like any bohemian quarter, by day Sopocachi feels slumberous, reflective. I see lots of street signs for dive bars, clubs, pool halls, and restaurants that only open after dark. But there are also bookshops and cultural centers, and I stop at the Salar Galeria de Arte, where the artist Gastón Ugalde is displaying his ultra-saturated photographs of Bolivia’s Uyuni salt lake. “It’s the whiteness,” he says of his obsession with the mineral. “It makes me think of death, which is so peaceful.” But he’s sipping a can of beer and grinning as he says it. Ambivalent, self-deprecating, and with a flair for Popstyle art, Ugalde is considered the Andean Warhol. “Tourism brought hotels and restaurants, and now the gastronomy will bring the kind of people who are collectors,” he says. “It’s a good time to be in Bolivia.”

I amble on, enjoying the relative calm of this western flank of the city, until I arrive at the Cementerio General, the main necropolis. Death here seems to be anything but peaceful. It is the Day of the Dead and all around me there is a commotion of mourners en route to tombs to recite prayers, picking up wreaths from the flower market at the gate, stopping by ice-cream parlors to buy cones—it’s traditional to enjoy something sweet after shedding bitter tears. The Aymara belief system holds that dead relatives are on a three-year journey to reincarnation. Thus mourners wail on the first Day of the Dead, weep politely on the second, and by the third are eating ice cream.

I make my way across to the old city, passing some of the guidebook favorites: El Mercado de las Brujas, where the cholas sell herbs, potions, and dried llama fetuses; Calle Jaén, probably La Paz’s oldest street and certainly the prettiest, with its cobblestones and shady patios; Lanza market, where tiny restaurants are full of diners bent over steaming bowls of broth, rolls stuffed with spicy sausages, and immense fruit cocktails. Cumbia music blasts out. Pungent aromas of spices, papaya, and pineapple waft along the walkways. This is as traditional a place as anywhere in the city, yet even here, a program called Suma Phayata (“well-cooked” in Aymara) is promoting food hygiene so visitors can go on a street-snack crawl knowing everything they eat is safe.

Over two lunchtimes, I explore a couple of central La Paz’s best new dining spots. Popular Cocina Boliviana, which I find above the inner patio of a decaying old house on Calle Murillo, is a lunch-only joint with a set menu that sparkles with creativity. Sitting at a bench by the open kitchen, I watch as half a dozen chefs—some of them Gustu alumni—turn out vividly colored stews, soups, and grilled fish dishes, plus native potatoes and legumes, decorated with flowers and herbs for a packed crowd. The food tastes delightful. The atmosphere is youthful and hypersocial. The price is almost embarrassingly bargain-basement.

(below) A vegan dish at Ali Pacha. Julien Capmeil

(below) Fruit stall at Mercado Lanza. Julien Capmeil

My favorite lunch pit stop, though, is Ali Pacha, one of the most progressive restaurants in South America. After training at London’s Cordon Bleu and working at Gustu, owner Sebastián Quiroga saw a film about animal welfare and had an epiphany: La Paz needed a vegan restaurant. The menu at Ali Pacha features roots and shoots, flowers and fruits: all exquisite to look at and thrilling to taste. I have crispy palm hearts, freshly whipped coconut butter, an “ash” made from beet, sweet quinoa, and ice cream made with cupuaçu from the rain forest. “It’s not unrealistic to think of our native cuisine as largely vegan,” he says. “Before cattle and sheep were introduced, the Aymara ate a diet of vegetables, pulses, and grains.”

Quiroga, like everyone I’ve met in La Paz, is hopeful, chatty, curious, ambitious (Ali Pacha has since added a café-bar, Umawi, specializing in locally produced spirits, craft beers, and wines from Bolivia’s Tarija region). Lots of these would-be movers and shakers have worked with one another before. This new generation of paceños is transforming the long-ignored city.

(below) La Paz at dusk. Julien Capmeil

To catch your breath in La Paz you may have to go even higher. The cable-car ride up to El Alto, a suburb that has become La Paz’s sister city, is steep and dramatic. From the top—I’m at 13,451 feet now—I can at last take in the sweep of the Bolivian capital. The crater in which La Paz sits looks like it was created by an asteroid collision—it is, in fact, a river canyon—and the city, too, has the look of something not quite intentional. Illimani acts like a purifying force, a pristine hulk of black mountain with its white summit, splitting the clouds and protecting this messy, crazy, breathtaking city.

I turn to enter El Alto, another million souls spread over the dusty Andean altiplano. Most visitors have to pass through because it’s where the airport is located, but in recent years some have lingered awhile to see one of the oddest artistic movements of our times.

El Alto native Freddy Mamani Silvestre, a former mason, has been giving this otherwise monotone sprawl an injection of color with some 60 houses inspired partly by native Aymara architecture, but also by festive chola clothing and—most bizarrely—the Transformers cartoon-toy franchise.

The buildings are known as cholets (from chola and chalet); the standard format is a multistory tower with retail space on the ground floor, a party venue on the first and second, a few floors of apartments to rent, and, on top, a house for the owner.

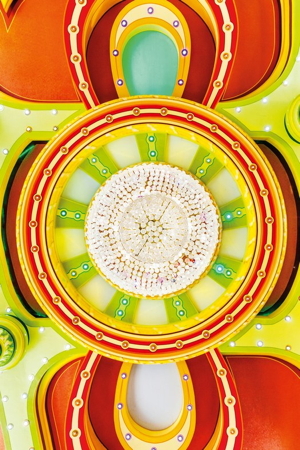

(below) A cholet. Julien Capmeil

I drive around a few of these cholets in a taxi. They stand out for their not-quite-primary colors, Wurlitzer-like lines, mirror-glass windows, and garish murals. We pull over at a ship-shaped building called Crucero del Sur. The interior is an acid trip of chartreuse, mustard, and carrot-orange. As a party venue, it’s indisputably fun—a mix of Willy Wonka, Gaudí, and Hansel and Gretel. As architecture, it’s an over-the-top cathedral of dubious taste for El Alto’s nouveau riche.

On the roof of the world, like a summiting mountaineer, I climb seven floors and come out onto a bare terrace. Before me is El Alto’s vastness, its endless rows of drab, jerry-built towers merging with the parched high plain. At the edge of this are the Andes, golden in the lowering sun, and a huge blue sky. I’m breathless again, but at least I’m standing still. From somewhere far below comes a faint hum: La Paz, tireless and unstoppable on its way to a new future.

Aracari Travel (aracari.com) offers a five-day trip to La Paz, from $1,650 per person, including lodging, private guided tours, and transfers. United, American, and LATAM fly from L.A., New York, Houston, and Miami via Lima, Peru.

[Below are 39 pictures from a Gallery in the article]

Go to original article to see larger pictures: CondeNast Traveler Article.

(below) La Paz high-rises. Julien Capmeil

(below) Mistura concept store. Julien Capmei........ (below) Ice cream. Julien Capmeil

......

......

(below) A cholet. Julien Capmeil...............................(below) A cholet. Julien Capmeil

......

......

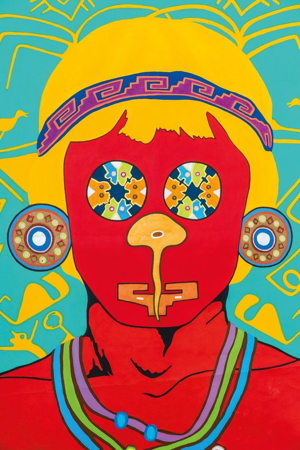

(below) Ugalde’s work. Julien Capmeil. ..................(below) La Paz high-rises. Julien Capmeil

......

......

(below) Dessert at Ali Pacha. Julien Capmeil.............(below) Cholet facades. Julien Capmeil.

....,

....,

(below) Oil paints. Julien Capmeil........................ .....(below) A bedroom at Atix Hotel. Julien Capmeil

.....

.....

(below) Potted plants outside Gustu. Julien Capmeil.......(below) A cholet. Julien Capmeil.

.....

.....

(below) La Paz from Mirador Killi Killi. Julien Capmeil .....(below) A cholet. Julien Capmeil

.....

.....

(below) Street art. Julien Capmeil PicS ....................(below) Day of the Dead wake. Julien Capmeil

.....

.....

(below) Colorful decor at Gustu. Julien Capmeil .(below) A chola display in Plaza Murillo. Julien Capmeil

.....

.....

(below) Bread at Gustu. J.Capmeil ..........(below) A headdress in La Paz’s folklore museum. J.Capmeil

.....

.....

(below) A vegetable dish at Gustu. Julien Capmeil .....(below) The Writer’s Coffee. Julien Capmeil

.....

.....

(below) Minibuses. Julien Capmeil ............................(below) Gastón Ugalde artwork. Julien Capmeil

.....

.....

(below)Yarns at the folklore museum. Julien Capmeil..√.(below) +591 Bar at the Atix Hotel. J Capmeil

.....

.....

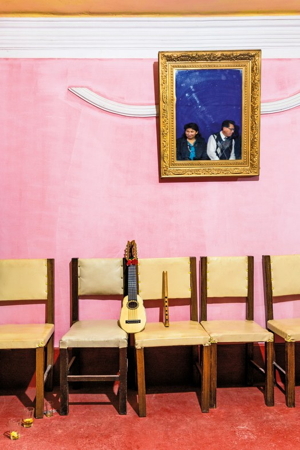

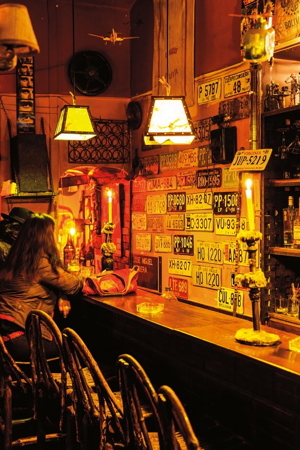

(below) The bar at Gustu. Julien Capmeil..................(below) The HB Bronze Coffeebar. Julien Capmeil

.....

.....

(below) The bar. Julien Capmeil...................................(below) Urban hills. Julien Capmeil

.....

.....

(below) Meringue at Gustu. Julien Capmeil....................(below) La Chopería bar. Julien Capmeil

.....

.....

(below) Old typewriter at the Writer’s Coffee. J.Capmeil.....(below) Day of the Dead shrine. J Capmeil

.....

.....

(below) HB Bronze Coffeebar. Julien Capmeil .....(below) Salteñas Potosinas pie shop. Julien Capmeil

.....

.....

(below) A sculpture. Julien Capmeil