How a populist president helped Bolivia's poor – but built himself a palace

March 7, 2019 - The Guardian

by Oliver Balch

The link between South American populism and declining inequality is striking – especially in Evo Morales’ landlocked nation

The whirr of a helicopter setting off from Evo Morales’ new 29-storey presidential palace sends the pigeons in a nearby square scattering. To critics of Bolivia’s longest-serving leader, the glass-fronted building adorned by a helipad is an alarming sign of the president’s increasing vanity.

Inocencio Carvajal Lopez, however, remains unfazed. For this 62-year-old indigenous leader, the sight of the bright red helicopter is, like the palace itself, a sign that Bolivia is at last on the up.

“This country has achieved tremendous progress with our brother Evo in charge,” Lopez says, describing Bolivia’s first ever indigenous president as “one of us”.

“The palace, the helicopters, the planes – thanks to these, the outside world can now see that our government is delivering development.”

Lopez, whose broad-brimmed hat carries the emblem of the ruling Movement for Socialism party, is not free of political bias. Yet the hard numbers bear him out. The percentage of people living in poverty in this landlocked South American state fell from 59.9% in 2006, when Morales first came to power, to 34.6% in 2017, with extreme poverty more than halving (from 38.28% to 15.2%) over the same period, according to government figures.

(below) Evo Morales’ palace in La Paz. Photograph: Juan Karita/AP

The statistics for Bolivia tally with a startling trend associated with populist leaders, particularly in Latin America. Their time in government is correlated with significant declines in economic inequality, according to new research by political scientists.

The academic group Team Populism discovered the correlation in an analysis of the Global Populism Database, which tracks populist discourse by world leaders.

The association between populist leaders and a decline in economic inequality holds true for a slew of Latin American leaders, mostly on the left, who use populist rhetoric in their speeches.

They include ex-leaders such as Peru’s Alan García, El Salvador’s Antonio Saca, Ecuador’s Rafael Correa and Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez.

Many of those presidential terms also saw declines in press freedom and a loosening on the constraints of executive power – traits that the researchers found are also associated with populist governments.

However, it was the link between populism and the shrinking gap between rich and poor that was most striking. And the drop in inequality under Morales was sharper than most.

David Doyle, an associate professor at the University of Oxford, says the correlation was difficult to explain and cautioned against drawing concrete conclusions. Over the last two decades, poverty and inequality levels have shrunk across almost the whole of Latin America, including several countries that have not had populist presidents.

The exception in the region’s inclusive growth story is Venezuela, a country that has been dominated by populist leftist presidents, but where substantial gains in poverty reduction in the past are now eroding fast due to the current economic meltdown under the embattled incumbent, Nicolás Maduro.

But Bolivia is a different story. Since Morales came to power in 2006, the country’s economy has grown at a steady 4.9% per year. For a country that had to be bailed out by its foreign lenders just one year before Morales became president, such macroeconomic success marks an incredible turnaround. But more remarkable still is that fact that this success is feeding through to the poorest segments of society.

Walk around the mountainous metropolis of La Paz and the evidence is in the bustling markets, the busy food courts, the queues for the cinema. Only you don’t have to walk, because a smart, Austrian-built cable-car network now connects the whole city.

While Bolivia appears to have undergone an economic transformation, the Chávez-like language of its president remains much as it always was. In a widely-broadcast speech in January to mark the 10-year anniversary of the country’s revised constitution, Evo, as he is known in Bolivia, addressed his audience as hermanos (brothers) no less than 34 times.

After reeling off a long list of his government’s achievements, he returned to his populist roots. “The poor and the humble will continue to be a priority for the state; it’s for them that we have won the elections,” he said, before pummelling a regular bogeyman. “Never again will foreigners take over our natural resources,” he declared triumphantly. “Never again a Bolivia humiliated.”

That rhetoric plays well with his supporters, the core of whom come from the ranks of Bolivia’s rural poor and unionised, blue-collar workers. But even the professional classes struggle to contest that life has got demonstrably better.

Asphalt highways, shopping centres, subsidised petrol, a stable currency and the minimum wage are just some of improvements cited by Julio Cesár, an engineer from Cochabamba. “I’m not a supporter of MAS [Morales’ ruling party] but my kids now go to a good college and I can at last afford a new house,” says Cesár, who now works in a state-run refinery but who for many years scraped out a livelihood working as a welder in his garage.

Doyle notes that all of the populist governments that oversaw reductions in inequality in his analysis were commodity producers. “This to me suggests that the commodity boom is probably responsible for a big chunk of what we are observing.” He adds: “These reductions may not be due to merit, but just to luck.”

In the case of Morales, whose ascent to office coincided with a prolonged commodity boom, both merit and luck appear to have played their role.

(below) Evo Morales in 2016. Photograph: Juan Karita/AP

He was elected just as international oil and gas prices went through the roof – a happy coincidence for a country with the continent’s second largest reserves of natural gas. Export revenues grew six-fold during his first term, from an average of $1.14bn a year over the previous two decades to $7bn.

Helping Morales’ record sheet was a long-running debt forgiveness programme, which saw Bolivia’s foreign debt more than halve (to $2.2bn) just as he came into office. The same happened with moves to nationalise key hydrocarbon assets, which had been agreed in the final days of the previous government.

But macroeconomic success doesn’t necessarily translate into reduction in economic inequality. Venezuela is proof of that. Despite its huge oil and gas reserves, more than half (55.6%) of its population still lived in poverty prior to Hugo Chávez coming to power.

The question is often how boom-blessed governments choose to spend their unexpected bonanzas. Wealth redistribution lies at the heart of leftist economic orthodoxy. Emblematic of such redistributive policies are cash transfer schemes such as Bolsa Família in Brazil and the Bono de Desarrollo Humano [Human Development Bond] in Ecuador.

Unlike traditional welfare regimes that cover everyone against generic risks such as unemployment or sickness, these social protection measures are designed to target specific vulnerable groups. “It a way of bringing lots more people under the social welfare net,” says Doyle.

Morales has not been slow to follow suit. Millions of poor Bolivians are now the beneficiaries of cash handouts, with particular focus given to the elderly, pregnant women, and low-income families with children.

The relatively small size of these transfers (or bonos), however, doesn’t entirely explain Bolivia’s success in narrowing the income gap. Alvino Mita, a 47-year old street vendor in El Alto, La Paz’s poorest district, laughs sardonically at the thought of retiring on the new universal state pension of 300 Bolivianos (£33) per month.

(below) Opponents of Evo Morales in La Paz, 21 February 2019. Photograph: Martin Alipaz/EPA

The payment is roughly equivalent to his days’ takings selling peanuts and dried bananas from his portable pavement stall: “I’m not saying it’s nothing, amigo, but it’s not much more than nothing either.”

That is not to say such government interventions have no impact. The minimum monthly wage, for example, now stands at 2,060 Bolivianos (£224), a threefold increase since Morales took power.

Yet such indirect measures can be regressive because they typically focus on workers in the formal economy, which accounts for less than half (44%) of the population.

For Ernesto Perez, a development economist with the United Nations in La Paz, one answer to Bolivia’s success in reducing inequality lies in state expenditure on basic infrastructure. According to its own figures, the government last year spent $6.5bn on schools, hospitals, power plants, electrification, irrigation and such like. In 2005, the figure was $629m.

Public investment on this scale brings direct jobs through construction, but its primary impact is to increase productivity, says Perez: “It’s like the post-War programmes that occurred in Europe, only they’re happening now in Bolivia 70 years later.”

Armando Ortuño, a political analyst, argues one factor overlooked by economics is the power of Evo’s leadership itself. “The very presence of having an indigenous president like Evo Morales in power has had an almost revolutionary effect … the symbolic ceilings that were in place before are no longer there,” he says.

(below) Paraguay’s president, Mario Abdo Benítez, with Evo Morales and miners’ leader Elias Colque. Photograph: Reuters

Gladys Mamani Larico is living that reality. The 21-year-old daughter of poor migrant parents has just started a cookery course at the social enterprise La Manq’a. Identified as indigenous Aymara by her plaited hair and layered skirts, she travels three hours by bus to the school in El Alto.

“In the future, I want set up my own restaurant,” she says. “Other graduates from the course have gone on to do that so that gives me confidence I can also do it.”

With elections slated for late October, the future is very much on Evo Morales’ mind as well. As one of the region’s few left-leaning populists still standing, the Bolivian president has his work cut out.

His decision to override a referendum against him standing for a fourth term has left many fearful of an autocratic turn in Bolivia.

The cost and ostentation of the new presidential palace (officially known as the Casa Grande del Pueblo) is indicative, critics argue, of Morales’ growing egoism and distance from those he claims to represent.

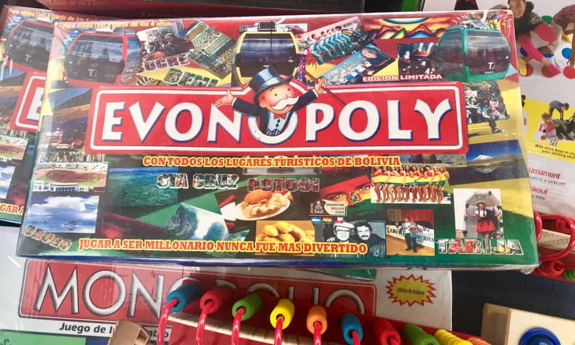

“Bolivia needs hospitals more than it needs grotesque buildings like this. The money it took to build the presidential palace could have built four hospitals,” says Sumaya Prado, a public relations manager. Critics also query the independence of the judiciary and say corruption is on the up (La Paz’s markets now sell a board game called Evonopoly).

(below) Evonopoly for sale in a market in La Paz. Photograph: Oliver Balch

If he is to be re-elected, Morales will have to adjust to a new political and economic landscape – one he helped bring about.

That will mean dealing with critics on the left who accuse him of being soft on private capital and presiding over a massive expansion in consumerism. He may also need to adapt his traditional populist appeals to the interests of the rural poor and unionised labour, which no longer hit home with a new generation of better-off young Bolivians.

How to modify the president’s rhetoric for a Bolivia in which nearly everyone has a mobile phone and access to credit is uppermost in the mind of Manuel Canelas, Bolivia’s youthful new minister of communications.

Looking out onto La Paz’s ever-expanding cityscape from the 16th floor of the presidential palace, he admits that the president can’t keep promising people what he promised 10 years ago.

Expectations have changed, Canelas says, and the message from everyday Bolivians is clear: “‘Don’t tell me that President Evo has built a new hospital; tell me that the hospital works well.’

That’s the challenge that we now face.”

(below) Dancers perform the traditional dance of the devils during carnival celebrations in Oruro, Bolivia. Photograph: Juan Karita/AP