(above) Main image: Firefighters try to control a fire near Charagua, close to the border with Paraguay. Photograph: Aizar Raldes/AFP/Getty Images

'Murderer of nature': Evo Morales blamed as Bolivia battles devastating fires

September 2, 2019 - Original article: The Guardian

by Dan Collyns

Runy Callaú can’t remember how many nights he has been fighting the blaze which has engulfed huge swathes of forest. Nor can he stop thinking about his encounter with a fleeing jaguar a few nights before.

“It was running for its life,” said the firefighter captain, peering out from under his yellow hard hat. “It was in a state of sheer terror.”

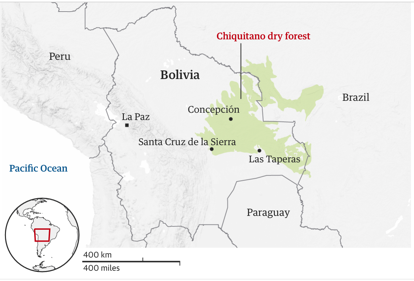

The jaguar is a feared but rarely sighted inhabitant of the Chiquitano dry forest, the unique ecosystem sandwiched between the Amazon and the Gran Chaco that has borne the brunt of weeks of fires in eastern Bolivia. At least 1.2m hectares (3m acres) have been destroyed.

All the volunteer firefighters report seeing terrified and burned animals: pacas, wild pigs, armadillos, tapirs and many bird species. On one occasion a rattlesnake climbed up Callaú’s leg before he kicked it away. “I caught my breath and realised it thought my leg was a tree,” he said. “It was just trying to get away.”

Thousands of fires swept through eastern Bolivia in August, to the fury of environmentalists and locals who accused the country’s president, Evo Morales, of incentivising the blazes after he passed legislation in July that encourages slash-and-burn farming to create pasture and arable land. Morales, who is running for a controversial fourth term of office, has refused to rescind the decree. His government says high winds and dry conditions are to blame for the worst fires in living memory.

(below) Armadillos and tapirs among wildlife caught in Bolivia’s fires – video

Tears rolled freely down Andrés Manacá’s begrimed face as he was embraced by colleagues and applauded by municipal workers in San Ignacio’s town square. He had returned with other firefighter volunteers after eight days battling the flames.

“It’s been a very hard experience because the fire nearly trapped me twice,” he said, his voice breaking. “The first thing I thought of was my family, but thank God I’m here now.”

Manacá and 14 other firefighters were dropped from helicopters into the forest more than 60 miles (100km) from the town, but soon found themselves fleeing flames that spread upward into the canopy so fast they created a fire whirl.

“It was violent, like lightning”, he said. “It felt like we were working to defend nature.” The unprecedented destruction of wildlife was also hard to stomach. Even following strict safety protocols, the men struggled psychologically, Manacá’s fire chief, Luis Andrés Roca, said.

“The stench of burned flesh was unbearable,” he said. “It’s nesting season and when the trees caught light the parrots died in their nests. My companions and I would cry, we felt so powerless. It’s the worst tragedy we’ve ever seen here.”

Global opprobrium has been focused on Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, over the record number of fires raging in the Amazon, the world’s largest tropical forest. Morales, Bolivia’s leftwing leader, is now facing similar anger.

The self-proclaimed defender of Pachamama, or Mother Earth, is accused of employing the same populist policies as his Brazilian counterpart. The fires were mainly started by small farmers who used the recent legislation to open up new land to farming and cattle, his critics say.

In La Chiquitanía, a boundless region of savannah and forest, August is the month of high winds when farmers typically carry out chaqueo, the practice of burning to clear land. But never like this, said Hernán Ramos, 76, who has lived all his life in Las Taperas, a village on its eastern edge.

“There used to be just small fires, they were controlled, not like now,” he said, pacing downcast over the blackened, ash-flecked earth. “These fires have surged in a way that there was no way to control.”

The Chiquitano dry forest is the ecosystem which connects South America’s two largest biomes, the Amazon and the Gran Chaco, a dense dry foreest of thorn-covered trees and scrub that extends south into Paraguay and Brazil.

With tall, papery-barked, often leafless trees, copious underbrush and daytime temperatures rthat reach up to 45C, few places in the world appear more flammable. It would only take a spark to set it ablaze.

On a three-day trip through the territory renowned for its Jesuit churches dating back to the 17th century, the Guardian saw a desolate panorama of scorched forests stretching for mile after mile.

Based on satellite images from Bolivia’s early warning fire detection agency, environmental groups estimate the destruction has surpassed 2m hectares. About 16% of the damage is within protected areas and fires recently spread into Kaa-Iya, Bolivia’s largest national park in the Gran Chaco.

Indigenous Chiquitano communities lost up to 98% of the forest they were working sustainably for timber and products such as copaiba oil, said María del Carmen Carreras of WWF Bolivia.

(below) Soldiers take a break from fighting fires in the Chiquitano dry forest. Photograph: Juan Karita/AP

Many locals blame migrant farmers moving from Bolivia’s highlands to the tropical lowlands for spreading the fires because they don’t know how to control them.

Standing across from a wooden colonial-era church painted with frescoes, San Ignacio de Velasco’s mayor, Moises Salcés, held up his hand as he named the culprit of the disaster. “The [human] hand,” he said, shaking his head wearily. “The cause is 99% indiscriminate slashing and burning.”

“You can’t just set the prairie alight. You have to pile up the wood and brush and cut it off with stones before,” said Arnoldo “Chichi” Vaca, a wiry driver for tourists visiting the area’s Jesuit churches. “These are outsiders who started these fires.”

That perception has stoked existing racial tensions between cambas – Bolivians from the eastern lowlands – and migrant collas – mostly indigenous people from Morales’s heartland in the western highlands, who are often looking to carve out a plot of land to farm.

Roly Aguilera, the secretary general of the eastern state of Santa Cruz, said the fires had spread because there were illegal settlements in the forest that “have been promoted politically by the central government”.

When Morales visited the town of Concepción on Friday, he was assailed outside the town hall by orange-clad firefighters who demanded to know why he had not visited them to thank them. Insults where exchanged between his supporters and detractors who shouted: “Evo, murderer of nature.” His office did not respond to a request for comment.

Morales has allowed in soldiers, planes and helicopters from mostly neighbouring countries to combat the fires, and last week he ordered that no agribusiness could be established on the burnt land. On Friday, he accused unspecified groups of paying people to to start the fires.

Such tensions were laid bare when protesters interrupted an event marking Bolivia’s first beef export to China last week in San Ignacio. Local media reported that as Morales sealed the first container of 96 tonnes of beef, demonstrators had chanted: “Behind every fallen tree there’s a laughing cattle rancher.”

Such tensions were laid bare when protesters interrupted an event marking Bolivia’s first beef export to China last week in San Ignacio. Local media reported that as Morales sealed the first container of 96 tonnes of beef, demonstrators had chanted: “Behind every fallen tree there’s a laughing cattle rancher.”

There was no laughter on the frontlines of the battle, where volunteer firefighters worked by night to keep cooler and better see the embers. “Agua!” went up a shout as beams from volunteers’ head-lamps illuminated the swirling smoke and ash hanging in the air.

Just half an hour outside La Concepción, the fire had consumed nearly everything. Twigs had become ash that could be brushed away like the tip of a cigarette left in an ashtray. A charred log pulsated white hot inside. The smell of wood smoke hang heavy and the ground was hot underfoot.

Dozens of volunteer firefighters who had come from cities across Bolivia complained they had received little support from the government.

“Reignition fire is a major problem, that’s why we have to be so thorough,” said Junior Tejada, a volunteer who had come with his brigade from Cochabamba. Like many others, he expressed rising anger at Morales’s slowness to act, and a growing sense of suspicion that the president shared some responsibility with the firestarters.

“What we’re doing to Bolivia and the Amazon is something that can’t be fixed even if we put out the fire now,” said Olivia Mansilla, an architect who took time off her job in Santa Cruz to volunteer. “What comes next will be a holocaust for nature.”