(above) Police near Peru’s Congress, in Lima, on Tuesday. Credit Paolo Aguilar/EPA, via Shutterstock

Who’s in Charge in Peru? Peruvians Can’t Agree

October 1, 2019 - Original article: New York Times

By Anatoly Kurmanaev and Andrea Zarate

Peru is facing its deepest political crisis in at least three decades, with the president dissolving Congress, Congress then moving to suspend the president — and the vice president, who had stepped up to lead the country, renouncing her position as well.

The vice president, Mercedes Aráoz, said late on Tuesday that she gave up her post because “the constitutional order in Peru is broken.”

The head of the dissolved Congress, Pedro Olaechea, who learned of her resignation in the middle of an interview with CNN en Español, said he would also not assume power — a tactical win for the president, Martín Vizcarra, but not the end of turbulence for Peru.

Peru’s dysfunctional and corruption-ridden political system has courted crisis for years, with three former presidents under investigation and another dead after shooting himself during his arrest. But matters came to a head when Mr. Vizcarra confronted the conservative forces controlling Congress and accused them of stonewalling his efforts to fight corruption and pass political reform.

On Monday afternoon, Mr. Vizcarra invoked a constitutional provision that allows him to dissolve Congress and to call new parliamentary elections. Congress responded by suspending him and setting off a constitutional standoff.

Protests in support of the president broke out in cities across the country on Monday night, but by Wednesday a tense calm had set in as the population tried to pick up their lives despite the political disarray in the capital, Lima.

While some Peruvians had celebrated Mr. Vizcarra’s decision as a much overdue purge of the corrupt elites, others saw in the drastic move a reminder of Peru’s despotic past.

Here’s what you need to know to understand this deep-rooted crisis that will shape the future of South America’s fastest-growing economy.

Why did the president suspend Congress?

Mr. Vizcarra claims the opposition, which controls Congress, has repeatedly blocked his attempts to clean up Peruvian politics and pass much-needed reforms.

The last straw for Mr. Vizcarra came Monday, when he asked Congress for a vote of confidence to change the system for appointing judges to the country’s highest court, the Constitutional Tribunal. This is the court that, among other things, arbitrates disputes between the president and Congress.

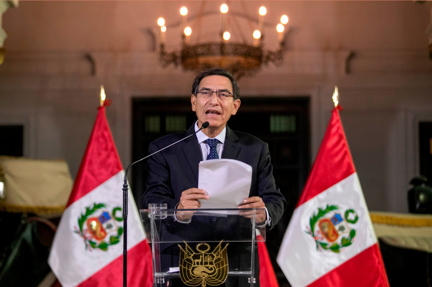

(below) President Martín Vizcarra announcing on Monday the dissolution of Peru’s Congress. Credit Juan Pablo Azabache/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Lawmakers gave him the vote of confidence, but also went ahead and picked a constitutional judge of their choosing: the cousin of the head of Congress.

But this showdown with Congress was likely only a matter of time, said Carlos Meléndez, a Peruvian expert at the Diego Portales University in Santiago, Chile.

Mr. Vizcarra, a regional politician turned vice president, is a relative outsider in Lima’s power circles. He took power last year when, facing corruption charges, the president, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, stepped down.

Although his anticorruption platform has been popular with Peruvians, and Congress is widely reviled as venal, Mr. Vizcarra lacks an electoral mandate and a strong party. His party occupies only five seats among the country’s 130 lawmakers.

His conservative opponents, led by the 54 lawmakers from the party of Mr. Kuczynski’s presidential rival, Keiko Fujimori, hold the majority of the seats.

Can he do that?

The Peruvian Constitution says the president can dissolve Congress if it twice denies his cabinet a vote of confidence.

But whether Mr. Vizcarra’s actions met that standard depends on whose interpretation of the law you accept.

Over the past year, Mr. Vizcarra asked for that vote three times, using a constitutional mechanism to package reform proposals as a vote of confidence in his cabinet. In all instances, Congress approved his cabinet but ignored his proposals.

On Monday, Mr. Vizcarra argued that Congress’s sleight of hand constituted a de facto vote of no confidence, giving him the right to shut down the legislature and call new elections.

“In spirit, the Congress had very definitely denied confidence to two cabinets; by the exact letter of the law, probably it had not,” said Cynthia McClintock, a professor of political science at the George Washington University.

(below) Supporters of Mr. Vizcarra outside Congress after he dissolved the legislature in Lima, on Monday. Credit Rodrigo Abd/Associated Press

Because the legality of Mr. Vizcarra’s move is uncertain, leaving open the question of whether Congress has been dissolved, it is also unclear whether it had the power to suspend Mr. Vizcarra and swear in his vice president, Ms. Aráoz. Peru now has a constitutional chicken and egg problem, said Michael Baney, a risk analyst at consultancy WorldAware.

“If the dissolution of Congress was legal, then it voting to strip Vizcarra of power was illegal, since it was no longer even in session,” he said. “Of course, the inverse is also true: If Vizcarra’s dissolution of Congress was illegal, then Congress was indeed in session and thus had the power to strip Vizcarra of his power.”

So what comes next?

The vice president, Ms. Aráoz, said on Twitter that she hoped her renunciation would lead to “general elections as soon as possible for the good of the country.”

Peru’s federal register on Tuesday published the date for new parliamentary elections: They are scheduled for Jan. 26.

Mr. Vizcarra has support from key stakeholders: He published photos Monday night of himself surrounded by Peru’s top generals, to show he has the army’s support. The police obeyed his order and surrounded Congress with riot shields to prevent most lawmakers from entering on Tuesday.

And manifestations of support for him erupted in various cities across the country on Monday, with smiling protesters jumping and shouting, “Yes we could.”

On Wednesday, Mr. Olaechea, the president of Congress, planned to meet with the caretaker commission of 27 lawmakers who by law manage the body while it is dissolved.

When asked during a televised interview if he would take the presidency, he said, “No, at this moment there is a de facto situation,” he said, referring to Mr. Vizcarra effectively remaining in control, with the army’s backing.

Holding up a copy of Peru’s Constitution, he said, “I can’t act any more than with this little book, which is the Constitution.”

Analysts say the resolution of the crisis is likely to fall to Peru’s courts, but even that scenario is uncertain. The main question is, which court? The struggle over appointments to Peru’s Constitutional Tribunal is precisely what set off the current crisis.

(below) Riot police surrounding Congress and blocking traffic in downtown Lima on Tuesday. Many businesses along the main avenues remained closed. Credit Martin Mejia/Associated Press

How are Peruvians taking this?

After a day in which riot police blocked traffic and many businesses along the main avenues stayed closed, downtown Lima was bustling as usual by Wednesday morning.

The markets have so far largely shrugged off the crisis. Peruvian currency, bonds and stock market recovered most of their initial losses Tuesday, as investors banked on both political camps continuing the business-friendly policies that have fueled Peru’s remarkable economic growth for the past decade.

The general mood in Lima’s middle-class districts Tuesday was a combination of joy at the prospect of breaking the political stalemate and uncertainty. Monday’s demonstrations by mostly young Peruvians in support of Mr. Vizcarra had been replaced by a tense calm.

To many Peruvians, particularly the young and the left-leaning, Mr. Vizcarra’s move is a chance to wipe the slate clean and finally reform the corrupt political system, which allowed the country’s traditional political parties to divvy up power and economic patronage at the expense of the country’s development for decades.

A less vocal section of Peruvians, however, has expressed concern about repeating the mistakes of 1992, when the country last faced a constitutional crisis. Back then, another political outsider, an agronomist descendant of Japanese immigrants, Alberto Fujimori — the father of the current opposition leader, Keiko Fujimori — dissolved the Congress with a similar discourse of national rebirth.

Mr. Fujimori then proceeded to rule with an iron fist, dismantling courts, staffing institutions with loyalists and committing gross human rights violations in his quest to stamp out dissent. His daughter’s party is still the largest force in Congress, epitomizing in its opponents’ eyes the political decay that her father ostensibly came to power to combat.

O.K., so what are the broader repercussions here?

Analysts warn that Peru’s political paralysis could soon begin to wear down the country’s steady economic growth, which has been fueled by mining and infrastructure investment. Peru’s 3.9 percent economic growth forecast this year by the International Monetary Fund is a sign of financial health on a continent plagued by stagnation, stock market runs and outright collapse in nearby Venezuela.

However, Peru’s basic economic model will likely remain untouched, regardless of which contender for the presidency comes out ahead.

“There are no signs at present that the favorable regulatory environment for the extractive sector, or the treatment of ongoing operational projects, will be adversely affected,” said Diego Moya-Ocampos, a political risk analyst with IHS Markit in London.

Peru’s foreign policy is also unlikely to change significantly. Both Mr. Vizcarra and Ms. Fujimori’s party have taken a tough stance against the government of Venezuela, whose economic collapse has triggered the biggest geopolitical crisis in the region in decades.

But a breakdown of the constitutional order triggered by this week’s events could come to haunt the country’s political center in the next elections, said Abhijit Surya, an analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit.

“The latest developments significantly heighten the risk that a radical, anti-establishment candidate will win the 2021 presidential elections,” he wrote in a note to clients Tuesday.