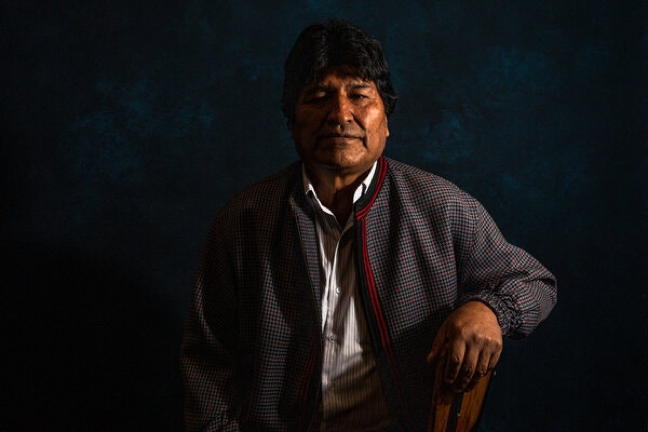

(ieft) Luis Arce, the handpicked candidate of the former president, Evo Morales, will be the next president of Bolivia.Tyler Hicks/The New York Times

How Bolivia Overcame a Crisis and Held a Clean Election

October 23, 2020 - Original article: New York Times

A presidential race that many feared would end in uncertainty or violence concluded quietly, allowing Bolivians to hope that a year of turmoil and threats to democracy may be behind them.

By Julie Turkewitz

LA PAZ, Bolivia — As Election Day neared, candidates fretted over the possibility of fraud. Voters across Bolivia questioned the solidity of the electoral process. And many worried that the result — any result — would provoke anger and violence from the other side.

But in the days that followed the vote, something unexpected happened.

The election went smoothly, and its results were quickly and widely accepted — an accomplishment that is being celebrated by many in a country that has weathered years of threats to its democracy.

“Democracy won in Bolivia,” said Fernanda Wanderley, director of the socioeconomic institute at the Universidad Católica Boliviana.

Exit polls on Sunday showed one candidate, Luis Arce, clearly taking the lead. His main opponent, Carlos Mesa, conceded the next day. On Friday, Bolivia’s electoral tribunal confirmed that Mr. Arce would indeed be the next president of Bolivia, matching the exit polls and voters’ expectations.

In the end, Mr. Arce won 55 percent of the vote, and Mr. Mesa had just under 29 percent, a win far bigger than Mr. Arce’s advisers had predicted.

(below) La Paz on Monday as Bolivians awaited an official election result.Tyler Hicks/The New York Times

Mr. Arce is the chosen candidate of the former president, Evo Morales, a towering figure of Bolivia politics. Mr. Morales is a socialist who transformed the country, lifting hundreds of thousands of people out of poverty and prioritizing Indigenous and rural communities in a nation that had been run for centuries by a mostly white elite.

The numbers indicate clear voter interest in continuing with Mr. Morales’s political project, and his party, Movimiento al Socialismo, or MAS.

But voters and analysts also say the election signals a promising moment for a democratic system that had been slipping under Mr. Morales, who bypassed the rules in his government’s own constitution to run for a third and then a fourth term, and was criticized for persecuting opponents, harassing journalists and stacking the judiciary in his favor.

His attempt to run for a fourth term last year ended in allegations of electoral fraud, and demands from opponents and protesters in the streets that he step down. Once police and the armed forces joined the call for his resignation, he left the country — and called his ouster a coup. Sunday’s election was a do-over of last year’s.

The president who has served in an interim capacity over the last year, Jeanine Añez, an opponent of Mr. Morales, has also persecuted her political enemies and stifled dissent, and infuriated many Bolivians by postponing the new election.

Her hard-line anti-MAS rhetoric, which made little distinction between party officials and everyday voters, turned off many Bolivians, said Raúl Peñaranda, a Bolivian journalist.

(below) The interim leader, Jeanine Añez, infuriated many Bolivians when she postponed the election.Federico Rios for The New York Times

In interviews, many Bolivians attributed the relative calm after the election and the high turnout for Mr. Arce to a yearning for stability.

In the country’s fewer than 200 years, it has seen 190 revolutions and coups. The last year included deadly protests, a presidential ouster, a health crisis that killed thousands, a financial crisis that has left many hungry and a contentious election that has riven the nation.

Mr. Morales, who was in office for 14 years, was Bolivia’s longest-serving president and presided over the country at a time when a commodities boom sent money flowing into the country.

Mr. Arce was his economics minister for much of that time, and is often associated with that prosperity and relative political stability. He has also promised to stay in office just five years.

All of this seems to have convinced more than half of the country to give him a chance.

“I think the crisis of the last year did a lot of damage to Bolivian democracy, part of an accumulative process,” said Ms. Wanderley. “But in the end, Bolivia found a path to overcome that crisis, and was able to conduct a clean, legitimate election in which the winner was decided by the popular vote.”

After Mr. Morales’s ouster, Bolivia also made a concerted effort to address mistrust in the electoral system.

It overhauled its electoral tribunal, which had been stacked with Morales loyalists. It also rolled out a voter education campaign and cleaned up the electoral rolls, said Naledi Lester, an election expert working in La Paz to assess the vote for the Carter Center, a nonprofit that has been observing elections since 1989.

Her colleague José Antonio de Gabriel, also working in La Paz, said the tribunal conducted an organized vote, and “acted with impartiality and independence and protected political plurality.”

Mr. Morales was forced out last year after his critics accused his government of trying to rig the vote in his favor.

The Organization of American States, which fielded the largest electoral observer mission in Bolivia last year, heavily criticized the 2019 process, concluding that election officials had engaged in “intentional manipulation” and “serious irregularities” that made it impossible to verify the result.

(below) Supporters of Evo Morales marched to La Paz last year after his ouster.Federico Rios for The New York Times

These irregularities included hidden data servers, manipulated voting receipts and forged signatures, the O.A.S. said.

Several reports by academics and policy experts have since criticized the organization’s statistical analysis of the election.

But the O.A.S. report has shaped the local and global narrative of the election. It has been used by Mr. Morales’s supporters to claim that global forces are conspiring against them, and by Mr. Morales’s critics to claim that MAS rigged the vote.

These differing views have sent people to the streets over the last year, sometimes resulting in violent clashes.

This year the O.A.S. sent 40 people to observe the election. On Wednesday, the organization issued a report calling it “exemplary” and “without fraudulent actions.”

The relatively smooth nature of the election may also have to do with who won.

Before Sunday’s election, Mr. Arce’s party had been a lead voice sowing doubt in the impartiality of the electoral tribunal. His supporters, in many interviews, often said that they wouldn’t trust the vote if he didn’t emerge as the victor.

“Arce is going to win, but they’re going to try and cheat him out of it,” said Graciela Fernández, 41, a produce seller, just days before the election. “Then there is going to be a fight.”

Mr. Mesa, on the other hand, said in an interview that he would “absolutely, categorically” accept the results if he lost. And then he did.

Mr. Arce’s criticisms of the electoral tribunal mostly fell away once he won.

“If the results had been different,” said Ms. Wanderley, “we could have had problems, grave problems.”

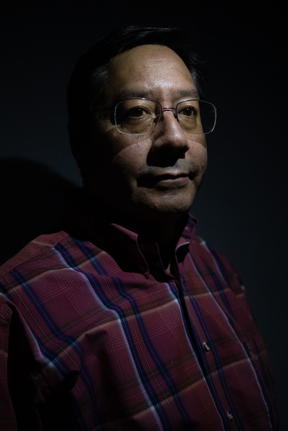

(below) Mr. Morales sat out the elections in neighboring Argentina.Daniel Berehulak for The New York Times