As Some Fret on Stimulus, Peru Goes All In and Gets Rewarded

April 7, 2020 - Original article: Finance Yahoo.com (Bloomberg)

Daniel Cancel and John Quigley

(Bloomberg) -- While Latin America’s two largest economies, Brazil and Mexico, fret over the wisdom of pursuing large economic stimulus packages that could erode fiscal targets, Peru is going big and getting rewarded.

First it led the way on direct payments to citizens amid the coronavirus pandemic -- pledging to put money in their hands before President Donald Trump first floated the idea for the U.S. Now the Andean country has unveiled a stimulus package that equals about 12% of its gross domestic product, the biggest in all of the Americas.

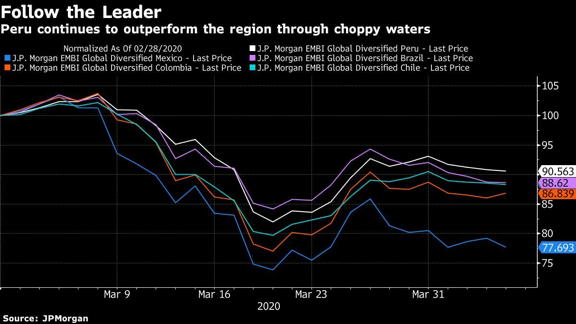

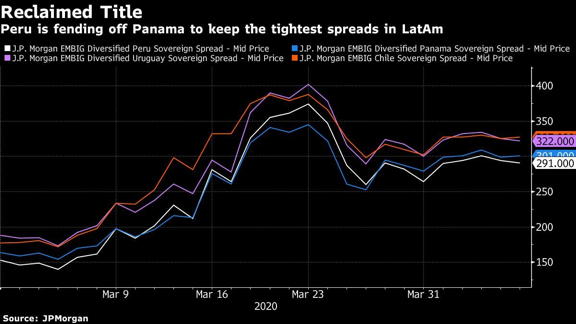

Normally, such a move would unnerve investors who have been burned repeatedly by fiscal largess in developing nations, but trading so far shows they approve of it. Even after congress passed a bill that would allow Peruvians to draw down a quarter of their pensions -- an amount equivalent to $8.8 billion -- local assets are outperforming. The sol posted the biggest gain for any emerging-market currency since the stimulus was announced March 29, while Peru’s country risk, as measured by its bonds’ yields over U.S. Treasuries, remains the lowest in Latin America.

“In this new coronavirus world, fiscal deficits are no longer a bad word,” said Guido Chamorro, co-head of hard-currency debt at Pictet Asset Management Ltd. in London. “Investors are taking the long view and rewarding countries that are being proactive in tackling the virus.”

One reason it’s easier for Peru to fire billions of dollars at the pandemic is because it has accumulated savings in the past decade equal to about 15% of GDP, or 117 billion soles ($34.4 billion). Mexico and Brazil are in much worse fiscal shape. Peru’s government can spend savings for now and only tap bond markets when conditions are favorable.

The populist measure from congress to free up 25% of pension funds initially drew investors’ ire, but Morgan Stanley has pointed out that money managers will likely divest liquid foreign assets and use cash balances to fund withdrawals and leave their domestic bonds and equity holdings largely intact. There’s also the possibility President Martin Vizcarra vetoes the legislation and negotiates a revised plan.

Peru also has access to the bond market. The scarcity of Peru’s dollar debt globally -- it has $9.3 billion outstanding -- helps to explain why its bonds trade as high as 140 cents on the dollar with yields of just 3.5%. Peru stands ready to expand the stimulus plan if needed and could tap debt markets, Finance Minister Maria Antonieta Alva told reporters on Monday.

Chile, which has been identified by analysts and investors as the other Latin American country best positioned to weather the storm, unveiled an $11.75 billion stimulus package worth close to 4.7% of GDP to confront the pandemic.

“Peru and Chile have very large rainy day funds which give them an incredible flexibility to weather this shock as long as it is a three- to four-month shock,” said Jens Nystedt, a senior portfolio manager at Emso Asset Management.

While Peru’s sol has gained 4.6% since March 27, Mexico’s peso has lost almost 3% and Brazil’s real is near a record low as those countries struggle to develop a cohesive strategy to fight the virus. Brazil’s pandemic spending plans amount to about 3% of GDP while investors are losing patience with Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador who is unwilling to push through any meaningful economic packages.

Why can’t other countries follow Peru’s path?

“It’s the lack of buffers that allow you to go for bigger packages,” Moody’s Investors Service analyst Jaime Reusche said in an interview. “It’s the worry about the impact that this might have on their funding needs, funding costs.”

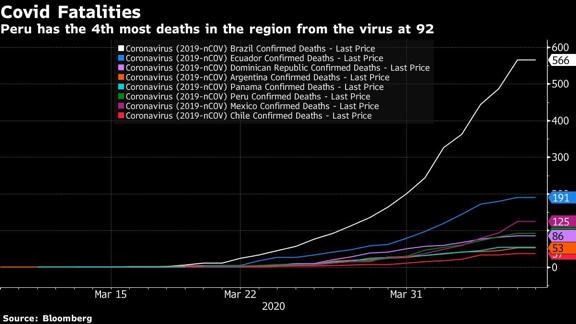

Of course at this stage it’s too early to say if Peru’s relief efforts will be enough, or if more budget-busting spending may be required down the line. After shutting the country of 32 million people down at the onset of the virus pandemic, Peru has reported 2,561 cases with 92 deaths while posting the biggest number of recovered patients in the region.

Moody’s expects the budget deficit to blow out to 9% of GDP this year from 1.6% in 2019 and for the economy to shrink between 4% and 10%. But that shouldn’t necessarily impact its credit rating.

“It’s better to take the hit now rather than to be stuck in a rut and not find a strong recovery on the economic front and have this crisis drag out,” Reusche said. “The fact that there is a plan with very strong movement control measures and a strong fiscal stimulus to mitigate the impact on the economy is seen as quite favorable.”